Modern Western education traditionally emphasizes two skills: the ability to process text and numbers. The importance of images, however, is often overlooked. While mainstream public schooling treats pictorial information as peripheral, a quick glimpse at the world around us can contradict this strategy. From television screens to billboards to magazine ads, images are everywhere, shaping and imprinting the minds of impressionable children and adults alike. To be illiterate in the realm of images leaves one powerless to criticize and create in a predominately image-driven culture.

The Guggenheim Museum in New York City has long been working to give children the opportunity to attain what they call “visual literacy,” a working understanding of what images are and how they work. Now in its 44th year, Learning Through Art is an educational program that provides elementary schoolers throughout New York public schools with the chance to spend 90 minutes a week focusing on art: looking at it, reflecting on it and, of course, making it.

In the 1970s, New York found itself in a fiscal crisis, on the verge of bankruptcy. As explained by Susan J. Bodilly and Catherine H. Augustine in Revitalizing Arts Education Through Community-Wide Coordination: “The arts and arts teachers became easy targets for budget cutting. As an example, in 1975-1976, after a decade of crisis and constant budget cuts, the New York City public schools laid of 15,000 teachers, almost 25 percent of the total number. Teachers in subjects considered ‘less central’ were the first to go. According to the the Center for Arts Education, ‘By 1991, the last year for which systematic arts data was collected by the Board of Education, two-thirds of the schools had no licensed art or music teachers.’ Schools were no longer allowed to hire arts teachers, and arts teachers who remained were transferred to other positions.”

In response to the massive cuts in arts funding in schools across New York, Natalie K. Lieberman, a member of the Guggenheim’s development department, launched a program initially called Learning to Read Through the Arts. The initiative, which began as an independent program housed within the Guggenheim, provided arts education to public elementary school children across all five boroughs of New York. It continued through the mid-1990s with substantial contributions from Lieberman, until she passed away, and the museum absorbed the program.

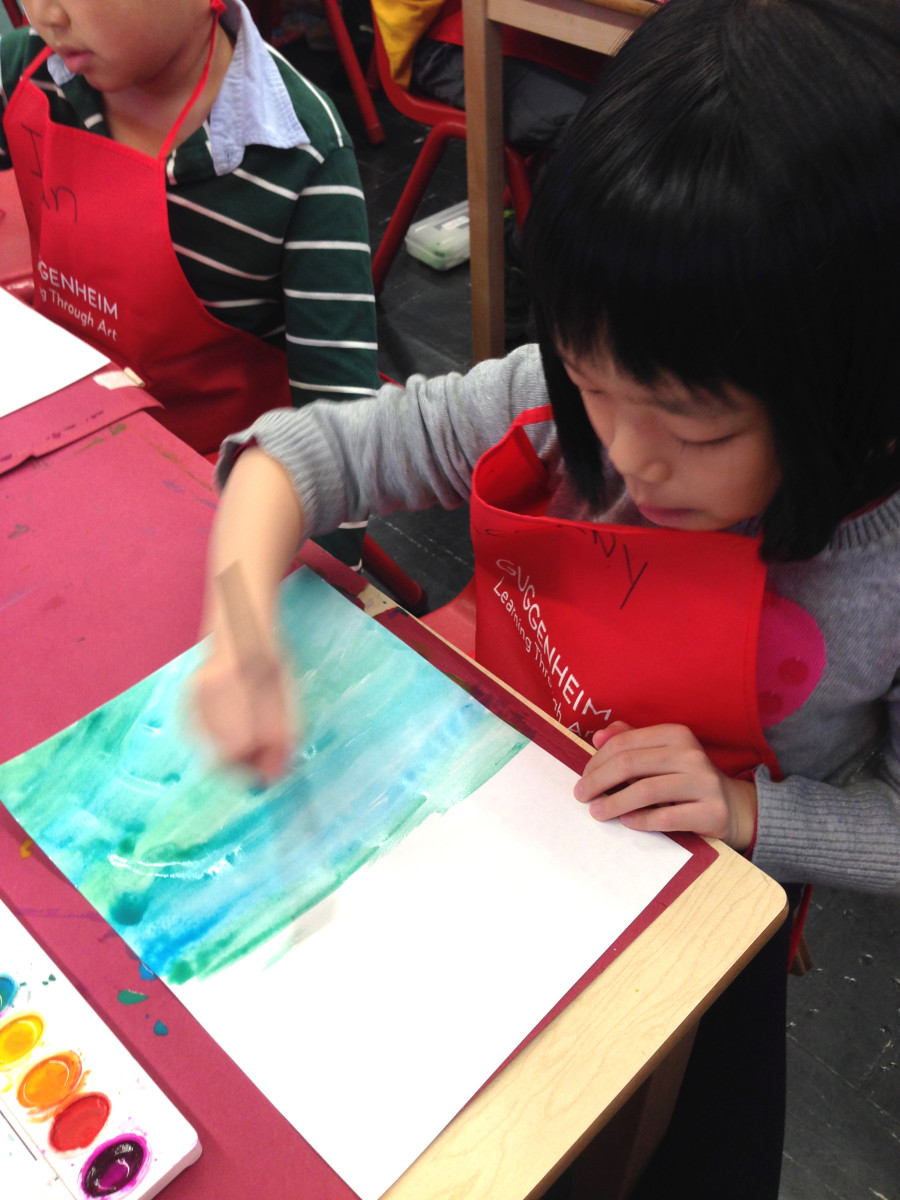

The name soon changed to Learning Through Art (LTA), more accurately capturing the broad aims of a curriculum that extended well beyond reading. It’s continued this way ever since. Each year, for 20 weeks, a teaching artist collaborates with a classroom instructor on an artistic curriculum that incorporates both themes from a central syllabus of coursework and the artworks currently on view at the Guggenheim. The syllabus includes hands-on art projects, discussions based on historical and contemporary artworks, as well as a final art project — all of which revolve around a single theme, or “essential question.”

“Every residency has an essential question that connects all the projects you do throughout the year together,” teaching artist Molly O’Brien reiterated to The Huffington Post. And the culminating works don’t just go on view in the teachers’ lounge; they get their very own wing at the Guggenheim, on view alongside works by artists like On Kawara and Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian.

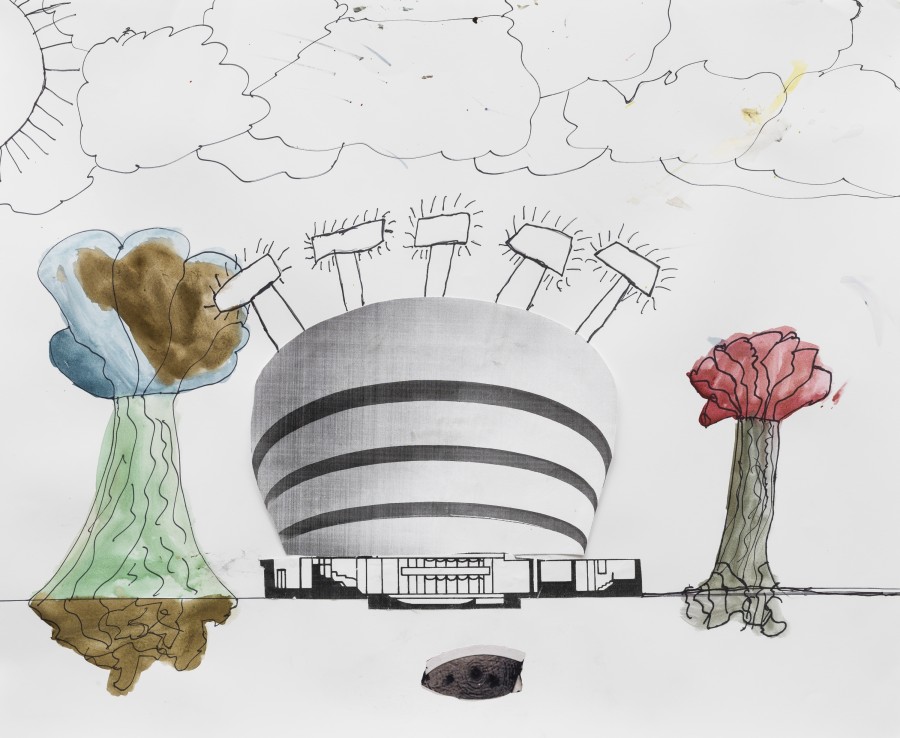

This year, O’Brien teamed up with fourth-grade teacher Deborah Sachs at PS 86 in the Bronx, who has been participating in LTA for 13 years. Their “essential question” was inspired not by a particular piece at the Guggenheim but by the structure of the museum itself — the iconic, spiraling edifice designed by Frank Lloyd Wright in 1959.

“Our question was, ‘How does where we are affect how we move?'” O’Brien explained. “We looked at the designs of spaces and environments and how we move through them. The students designed models of what their ideal schools and classrooms would look like. We talked a lot about Frank Lloyd Wright’s perspective on architecture. Surprisingly, these third graders can talk a lot about organic architecture.”

These questions, challenging to say the least, would likely intimidate an undergraduate art student, let alone an elementary schooler. But, as O’Brien put it, “the kids rise to the challenge every time.” For example, she taught a second classroom this year, aside from Sachs’ group, with a curriculum that revolves around the query, “How can we time visible?” To answer it, the class discussed the different ways time is experienced, witnessed and documented, both in life and in art. She described it as “pretty conceptual.”

The students and teachers also engage in a daily inquiry, focused on one specific work of art, frequently one found in the Guggenheim’s collection. Using open-ended questions, the teachers facilitate powerful discussions that can last over 30 minutes on a single work of art. “Depending on the background of the students, this idea of asking them a question that doesn’t have an answer is a really foreign concept to them,” O’Brien said. “By the end you realize those conversations have so much more power and momentum and the potential to be really deep. They often go on for way longer than I’d expected, which is pretty impressive for nine and ten year olds.”

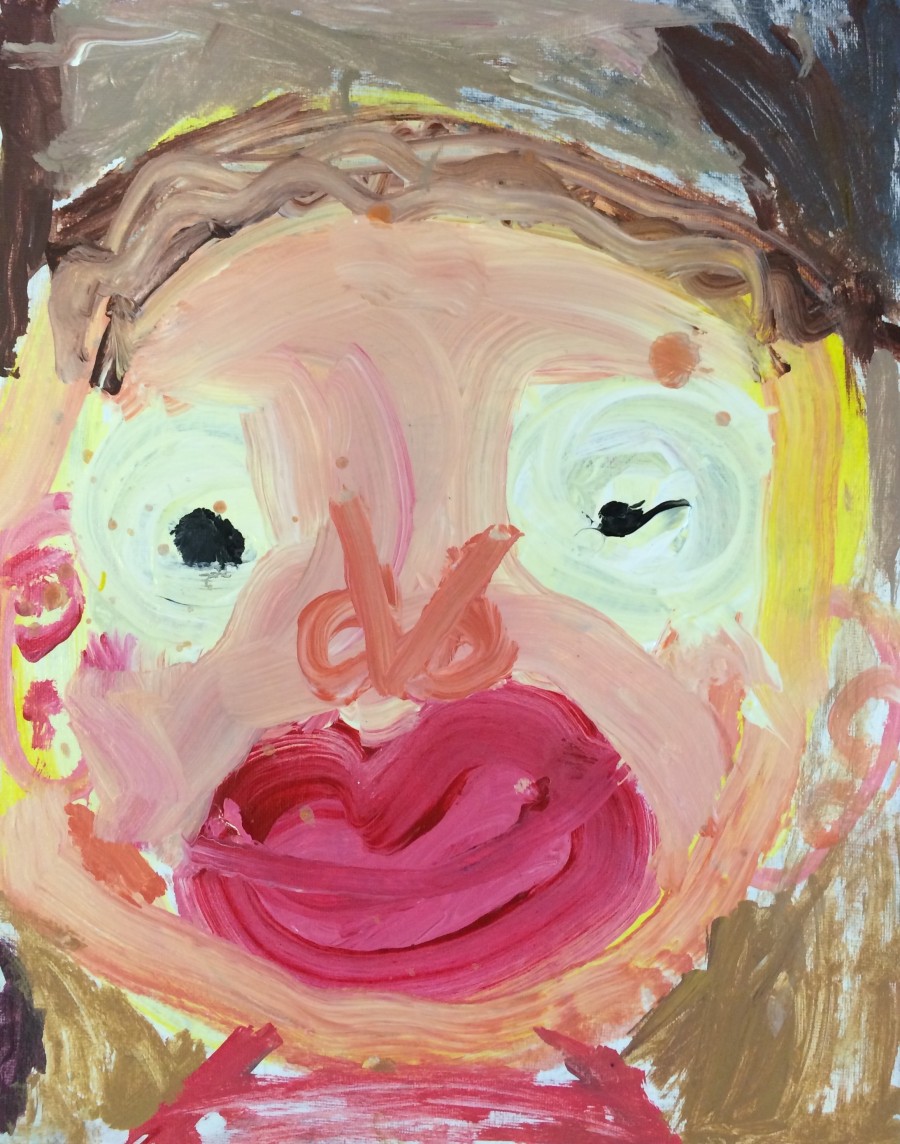

The discussions also allow students to communicate in different ways, often with images of their own, a practice beneficial to those who may not have confidence talking in front of a group to express themselves. “It gave the students more of a choice in how they were learning or how they were participating,” said O’Brien. “It’s amazing for me to see often in the final weeks that students may not have been as vocal are volunteering to share their artwork.”

“The students are making art, looking at art, and reflecting on the experience,” explained Greer Kudon, senior education manager of LTA at the Guggenheim. “Having students engage with the art, finding evidence for their statements, it all connects back to this idea of visual literacy.” Visual literacy is at the core of the program; the notion that navigating and understanding television, movies, ads and websites are necessarily skills in today’s world. In order to be an engaged citizen and a creative force, kids shouldn’t just be talking about books, they need to be talking about images.

At the end of the program, the teachers and staff confer to select around four artworks from each classroom to show as part of “A Year with Children 2015,” an exhibition at the Guggenheim. “What the teaching artists and the classroom teachers are looking for are works that exemplify the process that the students have gone through over the course of the year,” Kudon expressed. “It’s not necessarily the best figurative image or the best landscape, they’re looking for works that capture the experience that these students had. We also, from where I stand, are looking for gender equality. Obviously we want them to be aesthetically pleasing, but that’s very subjective.”

The opportunity to be shown in the Guggenheim, one of the leading modern and contemporary art galleries in the world, is one most artists spend their lives working towards. The magnitude of the experience is not lost on the kids. “Their art is in a wing just like Kandinsky’s art is in a wing, or Chagall’s,” Sachs said. “It’s open like any other exhibit is open to the public. You will see foreigners walking through and it’s unbelievable! I always joke with the kids and say ‘Jean-Francois will be visiting from France, and he will see your work as an example of New York art!’ What they gain from the experience — it’s enriching them in a way that, honestly, we can’t do in the classroom.”

Aside from the memories and pride associated with showing in a major museum, LTA provides children with tools that will assist them throughout their education, including literacy skills, problem solving, creativity and confidence. Two U.S. Department of Education grants have quantified some of the advancements actualized by the art program. The first, “Teaching Literacy Through Art,” conducted between 2004 and 2006, explored the correlation between reading skills and artistic learning. “Across the board, it was proven there was improvement in literacy for students who went through the program,” Kudon explained. Specifically, as detailed in the study, “Treatment Group students were more talkative and used more complex language than did Control Group students.”

The second study, conducted between 2007 and 2009, was titled “The Art of Problem Solving,” and examined children’s problem solving and creative skills, breaking down this somewhat abstract concept into six more measurable components. The results showed that three out of the six targets showed improvement –flexibility, connections of ends to aims, resource recognition. (The other categories were imagining, experimentation and self-reflection.)

As summarized in the study: “In plain language, the findings indicate that students who participate in LTA are more likely to plan, persist, be deliberate and thoughtful, approach difficulties with focus, and have greater knowledge of art materials. On the other hand, students who participate in LTA are no more likely to imagine beyond the task at hand or self critique, and they are less likely to try a number of materials.” Kudon hypothesized the satisfactory but not exceptional status of the results stems from the kinds of questions being asked in the particular study. “I think the realization was that these are much harder skills to evaluate in terms of children’s success.”

Some stories, however, make the triumphant outcomes of LTA more than obvious. “A few years ago when the earthquake occurred in Haiti, I had a child come to my class who had lost his house and his grandparents,” Sachs explained. “He was put into my class because he spoke French, as do I. He didn’t speak a word — nothing. I remember taking him to the Guggenheim and thinking, this is going to be interesting. As if he wasn’t already shellshocked enough from the country, the city, the school, the language. Right away, he was immersed in this unbelievable artistic experience. Suddenly he was the star of the class, the nicest kid, everyone loved him. He wasn’t the most amazing artist in the world, but he loved it all the same.”

This year, the Guggenheim is conducting a small grassroots evaluation of the program’s effect on children by following six students at four of the participating schools, two performing under grade level, two at grade level, and two above grade level. Kudon explained: “We’ve done a lot of interviews with these students, asking them about their experience with LTA, what subjects they like best in school, if they ever think about LTA in their other subjects.” They also get feedback from the classroom teacher, the teaching artist and the parents of each child. The results of this evaluation will not be available until the end of the program.

For what it’s worth — and that’s a lot — the kids love it. “LTA brings my mind to life, and we are very fortunate to work with The Guggenheim,” fourth grader Nashary Altamar wrote about her experience. “LTA is a way to learn how to do art and learn how people made art,” added classmate Christopher Macato. And from Sachs herself: “It’s an hour and a half of the day where kids’ minds can wander. In a way, the program and the trips enrich the children’s lives in ways the curriculum can’t. It’s truly a gift that’s given to the children.”

Our daily lives are saturated with an overabundance of magazine spreads, commercials, printed ads, pop-ups, and countless other graphic signals and signs. “It’s a language of words and images which calls out to us wherever we go, whatever we read, wherever we are,” John Berger said in his iconic 1972 television series “Ways of Seeing.”

Learning Through Art offers up a new model of digesting this overabundance, a model that views understanding art and images not as subsidiary skills for the bourgeoning mind, but a crucial element of being an engaged and purposeful citizen.

“A Year With Children 2015” runs from May 1 until June 17, 2015, at the Guggenheim Museum in New York City.

Sent from my Tricorder