The Art War Waged During the Great War

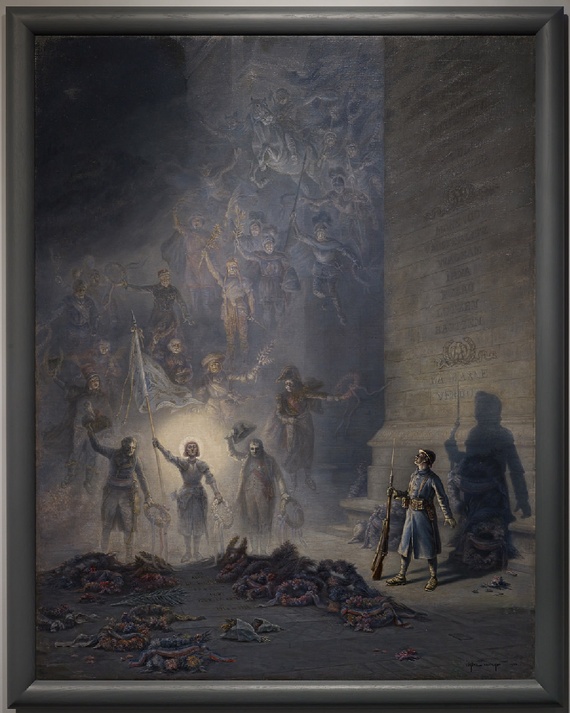

Detail of “I Have You My Captain. You Won’t Fall,” Paul Iribe, June 1917 (Courtesy of The Getty)

The war to end all wars was fought not only on battlefields, but on easels, drawing boards, and sketchpads.

2014 marks the 100th anniversary of the start of World War I, a battle fought famously by the world’s great powers. But two ongoing museum exhibits show it was also fought by artists, who brought images of the battle to the home front. The Getty Research Institute’s World War I: War of Images, Images of War (ongoing through April 19, 2015, Los Angeles) and the Wolfsonian-FIU’s Myth and Machine: The First World War in Visual Culture (until April 5, Miami Beach) examine the role pictures, posters, journals and expressive media played in selling the first modern mechanized war to the public. But they also show the way art portrayed its horrors: Propaganda and sanitized reportage collections are displayed together with raw eyewitness commentaries and visual allegories to reveal how the war was told differently through the new visual mediums.

“Understanding the continuities and differences between the use of images in World War I and past wars was a key—perhaps the key—curatorial concern for us,” said Gordon Hughes, an assistant professor in art history at Rice University and co-curator of the exhibit at The Getty. What changed, he noted, is that the conflict was packaged and sold on both sides as a war between cultures, with the end goal of determining which was best suited to lead Europe into the modern era.

The materials in the Getty exhibition evince the larger struggle for cultural dominance. The anti-opposition propaganda sometimes emphasized cultural traits that had little or nothing to do with the actual war: The French ridiculed German sausages and beer, clothing and fashion, bombastic Wagnerian opera, alleged body types, and modern art (German expressionism and Cubism). The Germans in turn “ridiculed the French as decadent, effeminate, inefficient, frail, and superficial,” Hughes said, which were supposedly reflected in their food, dress, bodies, music, and art.

Meanwhile, a generation of traumatized artists on both sides made art that was poignant, cautionary, and incendiary. The work of those who rebelled is examined in the books complementing both exhibitions: The Getty’s Nothing But the Clouds Unchanged: Artists in World War I (edited by Hughes and Philipp Blom) and the Wolfonian’s Myth + Machine: Art and Aviation in the First World War (written by Jon Mogul and Peter Clericuzio).

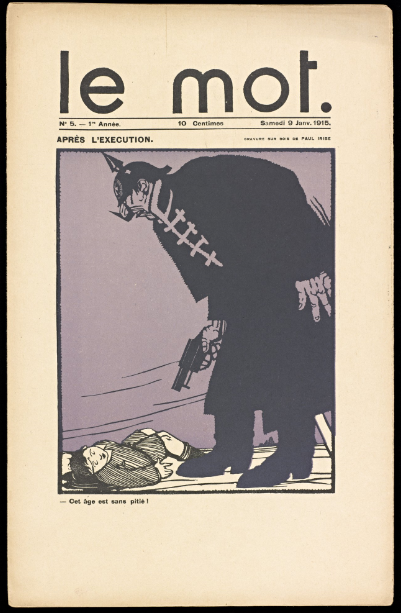

Yet not all the artists were dissenters. For those who served in combat roles directly there was little time, opportunity, or access to materials to produce artworks, Hughes explains. And for those who could not serve in combat—often due to age or health—designing visual warfare was their way of contributing. That was the case with one of France’s leading avant-garde artists, Jean Cocteau, who both volunteered to drive an ambulance and published the anti-German Le Mot with the illustrator Paul Iribe. According to Hughes, Le Mot mobilized a French modernist aesthetic that was overtly propagandistic.

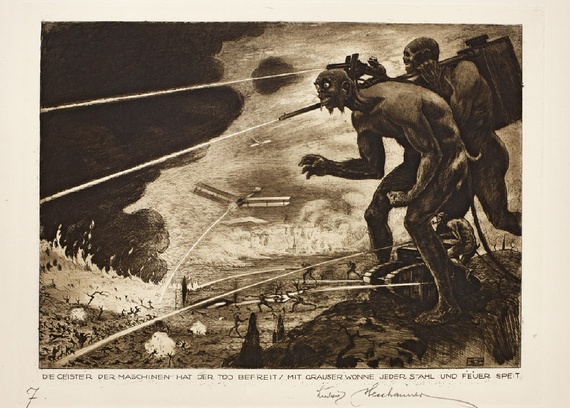

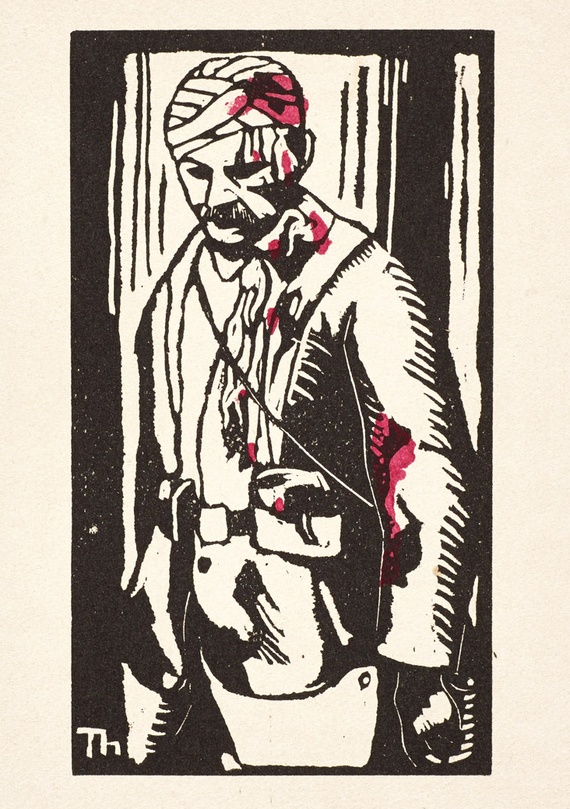

Battlefield carnage was so nightmarish and unprecedented that a new language had to be created to visually and textually describe it. “Most artists and writers, even those who were fairly aesthetically conservative prior to the war, tended to view traditional forms of image making or writing as wholly inadequate to the task of representing the experience of modern warfare,” Hughes said. He pointed out Italian Futurism, and the watercolor drawings on cigarette boxes by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner as examples of the period’s new visual vocabulary. It was, he said, an “effort to find a visual or written idiom that could represent, even if inadequately, what by its very nature cannot be represented.”

How did artists and designers choose to represent the unrepresentable? That’s the questions driving the exhibit at the Wolfsonian, according to its curator, Jon Mogul. The typical answer in art history is that World War I was a trigger for avant-garde innovation, since the war alienated artists from the established culture. That’s not wrong, said Mogul, and there’s evidence for that in the exhibition—works by Wyndham Lewis and Paul Joostens that depict soldiers and machines as nearly abstract geometric forms, a poster by Jean Carlu that incorporates a photo of a badly disfigured French veteran.

But Mogul was just as fascinated by the resilience of conventional, unrebellious depictions. Despite the rise of Cubism, Expressionism and, later, Dadaism, Mogul says that if you look at the art of period broadly, there’s more there than the modern-leaning, angsty stuff. He refers to a series of lithographs portraying the medical care of wounded British soldiers by an artist named Claude Shepperson, which avoided showing any evidence of wounds themselves or further suffering.

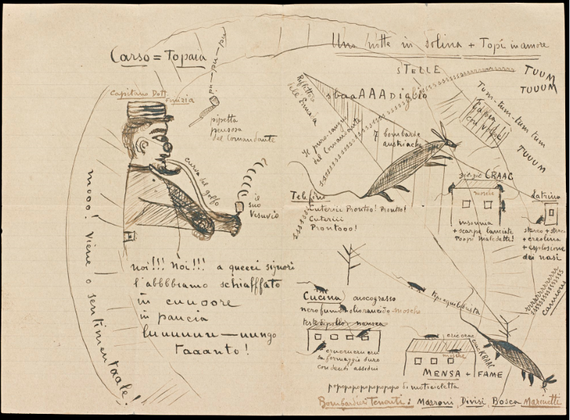

Nonetheless, plenty of raw images from the battlefield were altering the paradigms of pictorial representation in this period. Perhaps the most surprising instances are when sober images made their way into propaganda. Nancy Perloff, the curator of Modern and Contemporary Collections at The Getty and co-curator of this exhibit, cites Filippo Tommaso Marinetti’s parole in libertà (words in freedom) entitled The Carso = A Rat’s Nest: A Night in a Sinkhole + Mice in Love (c. 1917) as such an example. In the piece, a satire of a fellow Italian, the pipe-smoking, triple-consonant-speaking southern captain of the army camp, Marinetti combines sardonic humor with a depiction of realistic filth and vermin. The army camp, for instance, is surrounded by the hissing of enemy cannonballs and the “tuum tuuum” of shells. “We [usually] think of Marinetti as embracing war, but this parole conveys a more ambiguous message,” Perloff said.

When WWI is remembered today, it’s usually seen as a clash between armies. Perloff and Mogul hope that their respective exhibits will promote awareness that it was also a clash of arresting images. As Mogul noted, it was “an event that provoked as much disorientation and confusion among artists as it did among generals and statesmen.”