UN climate talks begin as global temperatures break records

Environment correspondent, BBC News

UN climate negotiators are meeting in Peru to try to advance talks on a new global agreement.

One hundred and ninety-five nations have committed to finalising a new climate pact in Paris by 2015’s end.

The process has been boosted by recent developments, including a joint announcement on cutting carbon by the US and China.

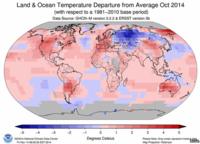

The two weeks of discussions start amid record-breaking global temperatures for the year to date.

According to the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (Noaa), the global average temperature over land and ocean from January to October was the hottest since records began in 1880.

There is likely to be plenty of heat at the UN meeting as well, as long standing divisions between rich and poor could, once again, hinder progress.

Delegates will try to finalise the key negotiating texts that will form the basis of the Paris deal.

Forward momentum

They will attempt to build on the this year’s positive momentum that has seen a new political engagement with the process.

In September, millions of people took to the streets of cities all over the world in a demonstration of popular support for a new approach.

Days later, 125 world leaders attended a meeting called by the UN secretary general, where they re-affirmed their commitments to tackle the problem through a new global agreement.

The chances of that happening were increased by November’s announcement from the US and China, with the Chinese signalling that their emissions would peak around 2030.

The European Union also contributed to the positive mood by agreeing climate targets for 2030.

There has also been good news on climate finance. The UN’s Green Climate Fund (GCF) secured over $9bn in commitments at a recent pledging conference in Berlin.

Now in Lima, the negotiating teams will try to boost these advances and maintain a momentum that will survive to Paris. But observers say there are many “formidable challenges” ahead.

“Ultimately this is not a problem that can be solved by just the US, China, and the EU,” said Paul Bledsoe, senior climate fellow with the German Marshall Fund of the US.

“There’s a whole series of countries – Canada, Australia, Japan, Russia, South Africa, Brazil and Indonesia – who have not made commitments (to cut emissions) and we don’t know yet how robust their commitments are.”

Form and function

One key element of the puzzle that needs to be resolved in Peru is the scale of “intended nationally determined contributions” (INDC).

By the end of March next year, all countries are expected to announce the level of their efforts to cut carbon as part of the Paris deal.

But, as yet, there is no agreement on what should be included or excluded from these INDC statements.

“Developed countries want a narrow scope for those guidelines, but developing countries are pushing for finance and adaption in them,” said Liz Gallagher from the think-tank E3G, and a long-time observer of the UN talks process.

“That seems to be a tactical move to make sure that finance and adaptation get more political attention than in the past – for me that’s where the big tensions in Lima will be.”

As well as the INDC discussion, there will be strong debate about what needs to be included in the final text. Parties are likely to clash over the long-term goal of any new agreement and its legal shape.

Many countries, including the US, have signalled that they will be unable to enter a legally binding deal on emissions cuts.

There will also be pressure for countries to come up with significant contributions in the period up to 2020 when a new deal is likely to come into force.

There are concerns that the scale of division between the interests of richer and poorer countries could lead to stalemate.

“I believe the developing countries need to be careful who they allow to speak as their leadership,” said Paul Bledsoe.

“I don’t believe that petrol states like Saudi Arabia or Venezuela are the appropriate leaders for the interests of less rich countries, most of whom do not have fossil resources.

“It is important that the great majority of developing countries who don’t have fossil resources don’t get gamed by those who do.”

Many attendees believe that the concerns about temperatures, and the engagement of political leaders, as demonstrated in recent months, will be positive for the process.

“I think, this top-down pressure will force countries to think they can’t always retreat to their old school lines,” said Liz Gallagher.

“Whether that will be positive or negative, I think that disruption to the negotiation dynamic is helpful at this stage.

“I think the countries’ ‘true colours’ will start to come out a bit. That’s useful for the public to know.”

Follow Matt on Twitter @mattmcgrathbbc.