Murder, but also reckless driving, drug overdoses, drinking, unruly passengers, and everything else

Shootings and murders surged in 2020, and while the 2021 increase appears to have been substantially smaller (as previously covered, this data reports with annoyingly large lags), the overall trend was toward more deadly violence in most cities, even as a few posted declines.

This has been a huge political fiasco for the substantively unsound notion of defunding the police and has also unfortunately kneecapped more reasonable reform ideas. But defunding police departments can’t possibly be the cause of the national murder surge because very few departments actually cut police funding. And while it would be a stretch to say the increase has been uniform, it has certainly been broad-based — red states and blue states, jurisdictions with reform DAs and jurisdictions with traditional ones, and even the handful of cities with GOP governors were all impacted by the rising tide of mayhem.

With that in mind, I think it is under discussed the extent to which we seem to be living through a pretty broad rise in aggressive and anti-social behavior.

Shooting someone is an extreme behavior, even in a country as violent and gun-soaked at the United States of America. But everyone has some margin along which they can get a bit more reckless, a bit more hostile, a bit more indifferent to the people around them. And as far as I can tell, a much larger swathe of the population is moving in that direction than the tiny number of people who are doing murders. You’re seeing more killing, which is a subset of the increase in shooting, which in turn is a subset of the large increase in gun-carrying. But traffic deaths are also up. Unruly passenger incidents on airplanes have surged. Schools report more discipline and student safety issues.

Basically, the murders seem like the tip of an iceberg of bad behavior. And while we need some tailored policy measures to address specific issues, I think we might also see some broad-based benefits in trying to restore a climate of normalcy.

The epidemic of dangerous driving

The United States has always had an unusually large number of motor vehicle fatalities because Americans drive more on average than residents of other rich countries.

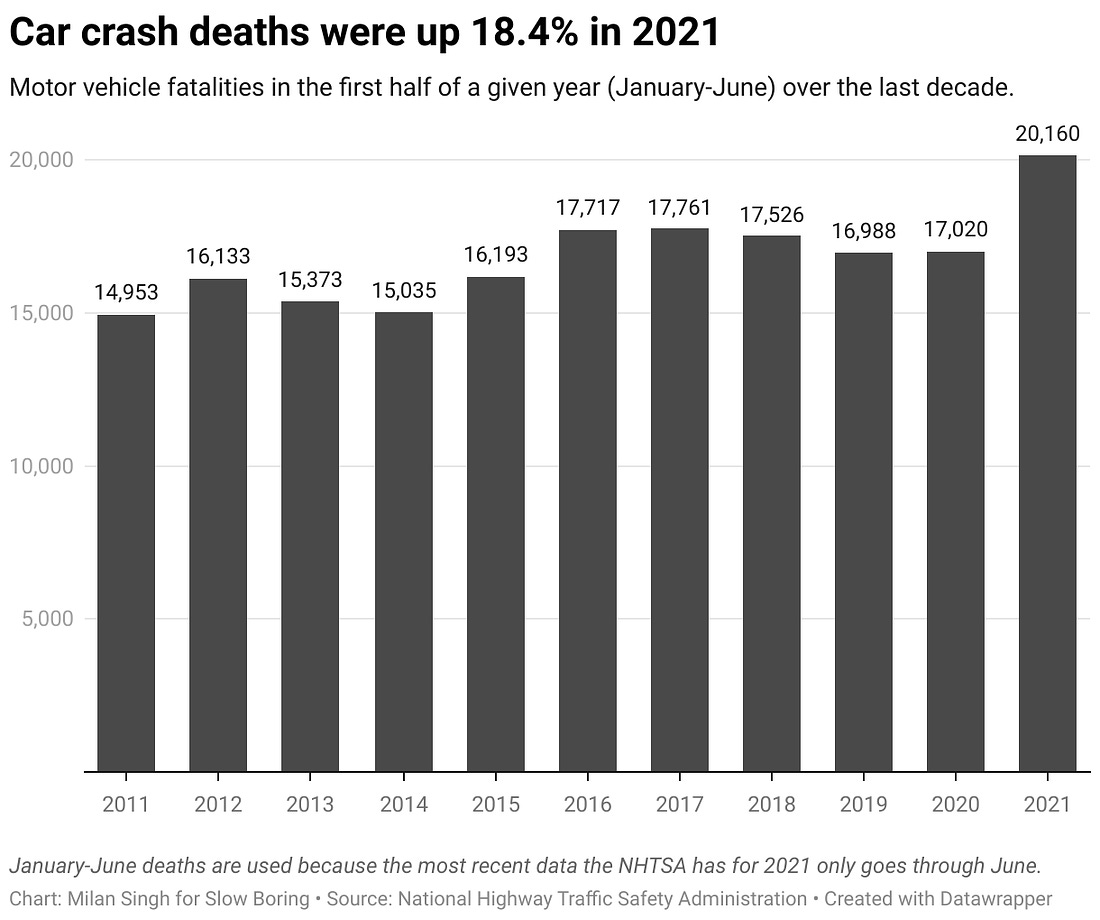

But in 2020, car fatalities didn’t decline despite the reduction in commuting volumes. And then in the first six months of 2021, we saw a huge increase in motor vehicle fatalities relative to before the pandemic.

Why did more people die? According to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, it was basically all of the things. If there was a way to make the driving experience less safe for drivers, less safe for passengers, or less safe for everyone else on the road, people did it.

NHTSA’s analysis shows that the main behaviors that drove this increase include: impaired driving, speeding and failure to wear a seat belt.

“Safety is the top priority for the U.S. Department of Transportation. Loss of life is unacceptable on our nation’s roadways and everyone has a role to play in ensuring that they are safe. We intend to use all available tools to reverse these trends and reduce traffic fatalities and injuries,” said Dr. Steven Cliff, NHTSA’s Acting Administrator. “The President’s American Jobs Plan would provide an additional $19 billion in vital funding to improve road safety for all users, including people walking and biking. It will increase funding for existing safety programs and allow for the creation of new ones, with a goal of saving lives.”

The safety measures Cliff mentions, some of which were funded by the bipartisan infrastructure bill, are all good ideas. As I said, the United States is a bit of an outlier among rich countries in terms of motor vehicle deaths, so it’s a problem we should try to address. But clearly the short-term rise we’re seeing isn’t a sudden deterioration in the quality of our transportation policy. People started speeding and driving under the influence more and wearing seatbelts less, and driving under the influence more.

Given how highly concentrated violent crime is in a relatively small number of neighborhoods, I think the typical American’s life is more at risk from reckless drivers than from murderers.1

And the change here is clearly coming from an increased level of misbehavior rather than from road design issues. But what’s interesting about reckless driving is how much more innocent-seeming and normalized it is. Driving your car too fast is nowhere near as dangerous to others as shooting a gun at someone is. So while only a tiny share of the public has ever shot someone, a huge number of people drive illegally fast at least some of the time. That’s what makes speeding so dangerous in the aggregate, lots and lots of people do it. And this seemingly unmotivated rise in speeding — especially when paired with other reckless driving behaviors — indicates to me that we’re looking at a general rise in misbehavior.

All kinds of institutions are reporting trouble

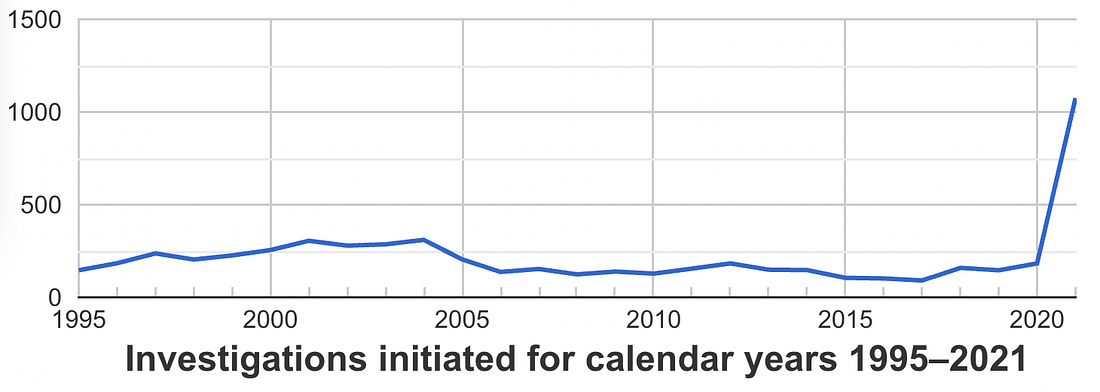

The Federal Aviation Administration’s data on the increase in unruly passenger investigations is frankly pretty shocking. In a proximate sense, this seems to be largely about mask rules. But is it really?

I’m a good mask-compliant liberal so I’d never think to get unruly about the mask mandate per se. But there’s plenty of occasion to be annoyed while flying on a plane and there always has been. Why do I need to take my shoes off? The mask thing has not made flying four times as annoying as it was in 2019. What’s happening is that people are experience less self-control and good judgment than they did before the pandemic, the same reason they’re driving more recklessly.

There’s been an increase in attacks on health care workers.

So maybe that’s political. People are watching Tucker Carlson and he’s getting them riled-up about vaccines.

But Roman Stubbs reports in the Washington Post that “As fans return to high school sports, officials say student behavior has never been worse.” And Chalkbeat and every other source I can find says school behavioral issues have generally gotten worse.