The test the president boasted about passing does not measure IQ but is typically used to check for early signs of dementia

Like any smart, down-to-earth person, Donald Trump has been bragging about “acing” a simple cognitive test he took recently. He’s been doing it for a while now, but it wasn’t until his interview with Fox News’s Chris Wallace on Sunday that he was challenged over it.

As the president started boasting about his results, Wallace laughed. “I took the test too when I heard that you passed it,” the Fox News host told Trump. “It’s not – well it’s not the hardest test. They have a picture and it says ‘what’s that’ and it’s an elephant.’”

This, according to Trump, was “misrepresentation”. “Yes, the first few questions are easy,” he conceded. “But I’ll bet you couldn’t even answer the last five questions. I’ll bet you couldn’t, they get very hard, the last five questions.” He added: “I guarantee you that Joe Biden could not answer those questions.”

So what is the test and are the last five questions, as Trump claims, really so difficult?

The test is called the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), and was created by the neurologist Dr Ziad Nasreddine in 1996. Talking to MarketWatch on Monday, Nasreddine stressed that the test “is supposed to be easy for someone who has no cognitive impairment”, stressing that “this is not an IQ test or the level of how a person is extremely skilled or not. The test is supposed to help physicians detect early signs of Alzheimer’s.”

There are a few different versions of the test with small variations (such as the words to remember or animals to name), but the questions are generally the same. We can’t tell for sure which version Trump took, but as he said he did it recently, I’ve taken the latest MoCA test from their website.

Trump is right about the start of the test being easy. But when it comes to the last five questions, his claim that they’re “very hard” is unsettling (although not surprising) in what it reveals about his relationship with reality.

But before we dive into that, here’s what the test involves:

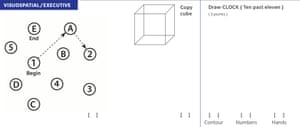

Drawing a clock and a cube

The first few questions are indeed “easy” – although it goes without saying that anyone experiencing cognitive problems is supposed to find it hard, and the point of the test is to help diagnose their condition.

First, you have to draw a line between numbers and their equivalent letters (1 to A, A to 2, 2 to B and so on). Then you have to draw a cube, and a clock at 10 past 11. Call it what you will – millennial-itis, lockdown brain – but this was actually a slight challenge as I can’t remember the last time I looked at a clock that wasn’t on my phone or laptop. So yes, it took me a second to remember that the minutes are all multiples of five – for 10 past the big hand points to two. But I figured it out in the end, and that’s all that matters.

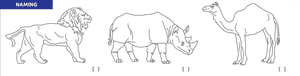

The ‘elephant’ question

If you’re lucky enough to not have any cognitive impairment, this part is also easy. There are three drawings – a lion, rhino and camel. As mentioned, there are a few versions of the test with very minor differences – for example, the test Fox News showed during the interview had an elephant on it (you can see it here), but the latest test has a rhino instead. This has led some of Trump’s critics to baselessly claim that he can’t tell the difference between the two.

Repeat after me – and do some maths

Both of these sections are very simple, and involve repeating a series of numbers forwards and backwards, and remembering a string of five random words. The final part, which Chris Wallace mentioned, asks you to count back from 100 in multiples of seven (100, 93, 86). Like the clock, this took me slightly longer than I would have liked – but nowhere does it say this is a timed test. I did it in the end, slowly but surely.

The difficulties begin

This is where things get a little concerning.

If you remember, Trump bet Wallace that he “couldn’t even answer the last five questions” of the test. But for a mentally healthy person, the last five questions should be as simple as the rest.

The fifth-to-last question on the test asks you to repeat a sentence out loud, before naming as many words as you can starting with F. In the following “abstraction” section, you have to spot the similarity between different objects such as trains and bicycles (modes of transport), or a watch and a ruler (measuring devices).

Next, you have to recall the random words that were included in the earlier memory section. This may be the part that’s easiest to trip over.

And finally, for the orientation part of the test, you have to … say what the date is.

For Trump to claim these are hard is worrying because for any cognitively healthy person, they shouldn’t be. But before we start any armchair diagnosis, you have to weigh up two probabilities against each other. Is it really likely that he found the last five questions hard? Or is it more likely that he’s misrepresenting about how hard they were, in order to look “smarter” than Joe Biden?

In the same interview, Trump got his team to pass him a chart that he said showed the US had “one of the lowest mortality rates in the world”, when it didn’t do anything of the sort. This is shocking, but not surprising – Trump has now made more than 20,000 false or misleading claims since he took office.

So it seems more likely that Trump’s difficulties at the end of the test tell us nothing that we don’t know already. His prolific lying and self-aggrandisement, two things we have empirical evidence for, should be what worries us. For, similar to his “stable genius” claims, you’ve got to ask yourself: how many smart people brag about their supposed intellect so much, and in such a misguided way?

America is at a crossroads …

… and the coming months will define the country for a generation. These are perilous times. Over the last three years, much of what the Guardian holds dear has been threatened – democracy, civility, truth.

Science is presently in a battle with conjecture and instinct to determine policy in the middle of a pandemic. At the same time, the US is reckoning with centuries of racial injustice – as the White House stokes division along racial lines. At a time like this, an independent news organisation that fights for truth and holds power to account is not just optional. It is essential.

The Guardian has been significantly impacted by the pandemic. Like many other news organisations, we are facing an unprecedented collapse in advertising revenues. We rely to an ever greater extent on our readers, both for the moral force to continue doing journalism at a time like this and for the financial strength to facilitate that reporting.

You’ve read more than in the last nine months. We believe every one of us deserves equal access to fact-based news and analysis. We’ve decided to keep Guardian journalism free for all readers, regardless of where they live or what they can afford to pay. This is made possible thanks to the support we receive from readers across America in all 50 states.

As our business model comes under even greater pressure, we’d love your help so that we can carry on our essential work. If you can, support the Guardian from as little as $1 – it only takes a minute. Thank you.