Firefighters battle a wind driven wildfire in the hills of Canyon Country north of Los Angeles, California, U.S. October 24, 2019.

Gene Blevins | Reuters

California’s biggest utilities aren’t the only U.S. companies grappling with the increased force and frequency of wildfires.

The number of S&P 500 firms flagging “wildfire” as a potential risk factor in annual reports has increased dramatically over the past decade — from 9 in all of 2010 to 37 so far in 2019. In just the past year, at least 14 companies in the S&P 500, including Marriott and Monster Beverage, have added wildfires to their basket of concerns in 10-K filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission. While many S&P 500 firms have included “fire” in the risk factor section of their 10-Ks, this analysis specifically accounts for “wildfire.”

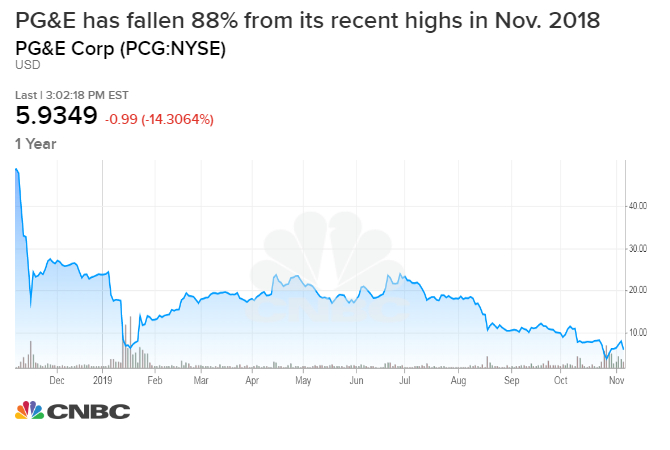

California-based utilities PG&E and Edison International have drawn much of the spotlight since 2017 and, more recently, as the two companies prophylactically shut off power to vast portions of their service areas in October. But, in just the past couple of years, businesses across an armada of industries have started to sound the alarm.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, real estate companies make up the largest share — 10 of 37 — that have flagged wildfire risk in 10-K filings this year. But concerns are spread across sectors from banking to biotech to semiconductors.

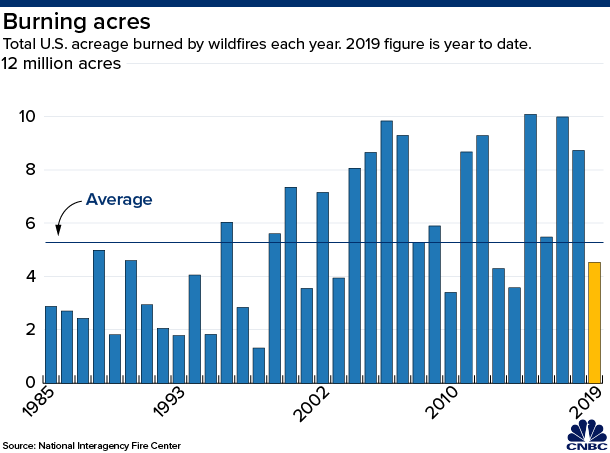

Those proliferating worries are reflected in the data. Ten of the 20 most destructive U.S. wildfires since 1923 have ignited in the last five years.

S&P 500 companies noting “wildfire” as a risk in their annual 10-K filings

A number of these companies have added wildfires to a burgeoning list of natural disaster threats, which include earthquakes and tornadoes. Orville, Ohio-based consumer giant J.M. Smucker, for instance, had flagged the risk of tornadoes to its production facilities in Kansas and Alabama in 2018. But, this year, the consumer giant added a new line on California wildfire.

Other firms have been more explicit in their warnings.

In its latest 10-K filing, Houston, Texas-based power infrastructure company Quanta Services warned investors that its current insurance coverage might not sufficiently account for wildfire risk.

“Should our insurers determine to exclude coverage for wildfires in the future, due to the increased risk of such events in certain geographies or otherwise, we could be exposed to significant liabilities and a potential disruption of our operations,” Quanta Services executives said. “If our risk exposure increases as a result of adverse changes in our insurance coverage, we could be subject to increased claims and liabilities that could negatively affect our business, financial condition, results of operations and cash flows.

Redwood City, California-based data center firm Equinix, meanwhile, has directly cited PG&E as it works to confront the surging wildfire threat. In January, PG&E filed for bankruptcy protection, saying it’s facing more than $30 billion in liabilities after it was determined that its power lines sparked last year’s devastating Camp Fire. The fire, the deadliest in California’s history, killed 86 people and left 30,000 homeless. The power company was also deemed responsible for 12 of the fires that tore through Northern California in October 2017, according to state officials.

While PG&E has said it will honor $42 billion in existing power agreements as a part of its plan to restructure and ultimately emerge from bankruptcy, escalating wildfire threats introduce further uncertainty for businesses across a swath of industries that rely on the utility. On Thursday, PG&E reported $1.6 billion in losses last quarter as it faces increased pressure from state and local officials.

“If PG&E seeks and is allowed to reject power agreements, it is difficult to predict the consequences of any such action for us,” Equinix executives said in their latest 10-K filing. “But they could potentially include procuring electricity from more expensive sources, reducing the availability and reliability of electricity supplied to our facilities and relying on a larger percentage of electricity generated by fossil fuels, any of which could reduce supplies of electricity available to our operations or increase our costs of electricity.”

But Equinix isn’t alone, and executives at a slew of companies — ranging from Comcast to Ulta Beauty to Corona brewer Constellation Brands — are closely monitoring probes into the spate of wildfires that have ravaged California since mid-October. At one point, 16 were burning across the state. As of Friday, all but one were fully contained, according to the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection. Local and state officials lifted all mandatory evacuation orders this past week but investigations are ongoing.

2019, a “below average” wildfire year to date

Despite several weeks of dangerous weather conditions and hurricane-force wind gusts as high as 102 miles per hour, the 2019 wildfire season has actually wreaked less havoc compared to the last two years. 2018 was not only the deadliest fire season on record for California, but with more than 1.6 million total acres destroyed, it was also the worst in terms of sheer scope.

Through October, however, 2019 has been a “below average” year for wildfires by several key metrics, according to researchers at Bank of America Merrill Lynch. Compared to the average seen during the first ten months of the years 2013-2018, wildfires in 2019 have burned fewer acres and destroyed fewer structures. There have been 314 so far in 2019 vs. 2,700, on average, over the same periods in 2013-2018.

Some industry experts contend this year’s fires have been less destructive in part due to improved safety and prevention programs.

“While many factors come into play, this data suggests that the more pro-active de-energization programs set up this year have helped mitigate wildfires,” Antoine Aurimond, research analyst at Bank of America-Merrill Lynch, wrote in a recent note.

Aurimond added that seven of the 10 most destructive wildfires between 2013 and 2018 were caused by power lines, suggesting state policymakers are right to hone in on utility equipment to reduce fire damage. Most recently, Southern California Edison, a subsidiary of Edison International, disclosed on Oct. 29 that its equipment “likely” caused the 2018 Woolsey fire, which burned nearly 97,000 acres, destroyed more than 1,500 structures, and killed 3 people.

But, as utilities turn to deliberate power shutdowns to limit future fires, companies in other industries are bracing for impact.

Eyeing more dangerous conditions ahead, PG&E CEO Bill Johnson said recently that planned blackouts would be necessary for the next 10 years as the company upgrades its electrical systems.

These preventive measures — which forced businesses and school districts to close this fall — have enormous economic ramifications. Michael Wara, senior research scholar at the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment, projected the economic cost of PG&E’s preemptive outages in early October — which impacted 800,000 customers, or nearly three million people — could top $2.5 billion. Other forecasts suggest that hundreds of millions were lost in costs stemming from spoiled food, and an estimated $30 million daily reduction in consumer spending.

“The scope, scale, complexity, and overall impact to people’s lives, businesses, and the economy of this action cannot be understated,” California Public Utilities Commission President Marybel Batjer wrote in a letter to PG&E’s CEO last month.

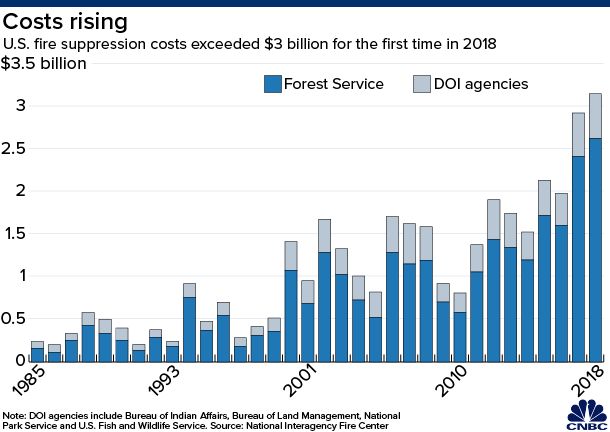

Corporate concerns have been compounded by rising wildfire suppression costs, which topped $3 billion for the first time last year, according to government data. Most of the costs center in California, which spent $947 million on fire suppression and emergency response in 2018, surpassing the $450 million allotted in the state’s budget. To keep pace with these heightened demands, the U.S. Forest Service, which shoulders most of fire suppression costs, said it now expects the fire budget to consume two thirds of its overall budget in 2019. That’s four years sooner than originally planned.

Many analysts suggest that number, which includes insurance claims and cleanup costs like debris removal, will balloon as climate patterns shift and California’s housing shortage forces residents into precarious areas.

California Governor Gavin Newsom added more support to help fight the latest fires, securing a grant from the Federal Emergency Management Agency earlier this month.

But, as wildfire seasons become more intense and expensive, that funding could come under pressure, adding more risks for businesses dependent on the utilities.

Mitigation strategies: tech solutions vs. rolling blackouts

Though the severe winds have abated, California is only midway through its fire season. Residents and companies could face more hazardous conditions before year’s end.

Aurimond and a team of researchers at Bank of America Merrill Lynch note that the most destructive wildfires in 2017 and 2018 occurred later in the calendar year. The 2018 Camp and Woolsey fires ignited in November, while the 2017 Thomas fire in Ventura and Santa Barbara counties sparked in December.

While several industry experts believe utilities have no choice but to initiate more power shut-offs in 2019 and going forward, some are testing new technology to improve local responses to fire emergencies.

Sempra Energy’s San Diego Gas & Electric relies on a network of 15 high-definition cameras that live-stream in fire-prone areas. The cameras capture evidence of dangerous conditions, allowing the utility to turn off broken or damaged power lines before they can spark fires. Southern California Edison has rolled out similar fire-monitoring cameras across Orange County, while PG&E plans to deploy 600 cameras throughout its service area between now and 2022.

Tech companies are also looking to fill the void.

Last month, software giant Splunk invested in San Francisco-based cloud startup Zonehaven, one of a handful of companies using big data to curb the state’s growing wildfire threats.

Aggregating data from controlled burns, real-time weather patterns, and satellite imagery, Zonehaven generates fire simulations that map out the path of the blaze and recommend specific evacuation sequences for residents.

“The real goal is to make sure that, in the first five to ten hours of a fire, we’re getting people out of the way,” Charlie Crocker, Zonehaven CEO and former Autodesk veteran, told CNBC.

Moraga-Orinda is one of several fire districts in the Bay Area that has partnered with Zonehaven, installing 15 ground sensors back in October 2018.

“These [severe wind] events often outpace the reflex time associated with calling for and delivering a response team,” Dave Winnacker, Moraga-Orinda’s fire chief, said. “The next step is providing not only the alert that something is wrong, but personalized recommendations about what actions should be taken.”

Winnacker added that he has had conversations with representatives at Waze, the navigation app owned by Google, about incorporating its traffic monitoring systems to enhance evacuation procedures. Google parent company Alphabet was one of six tech firms that cited “wildfire” risk in their latest regulatory fillings with the SEC.

But there are still concerns that regulation and policy in California aren’t yet sufficient for the technology to be rolled out in place of planned blackouts.

“We have been trying, but thus far unsuccessfully, to gain traction with the state,” Winnacker said.

Much of California policymakers’ recent attention has focused on PG&E, as Governor Newsom hosted meetings with the utility’s top executives last week. Newsom has threatened a public takeover of PG&E and appointed an energy czar to steer the company out of bankruptcy. PG&E must exit bankruptcy by June 2020 to take part in the state’s wildfire fund, which would help guard against future losses.

— contributed to this report.