Aimee Teese’s final words to her friend and outreach worker Michelle Langan were: “Look after yourself.” Hours later, on 8 January this year, she was found dead in a tent on the outskirts of Liverpool city centre. Within three months, on 2 April, Richard Kehoe was discovered comatose in a tent opposite the Royal Liverpool hospital. Soon after, he was pronounced dead.

Three days later, Liverpool’s mayor, Joe Anderson, announced he would remove all tents from Liverpool city centre. “We are going to give people a warning, give them an hour to take their tent down and say: ‘Here is a place for you to sleep, we will pick you up, take you with your goods.’”

It was a dramatic – possibly draconian – statement. Anderson called the policy tough love, and said there was no other option. He was not prepared to have homeless people dying on his streets, hidden in tents. “When Richard Kehoe or Aimee Teese die, then we have all failed,” he said.

Q&A

What is ‘The empty doorway’ – the Guardian series on people who died homeless?

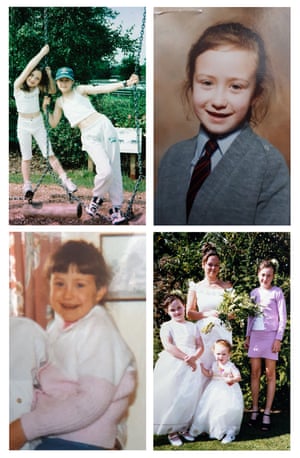

An estimated 800 homeless people died in Britain in the 18 months before March 2019. Over the next few months, G2 and Guardian Cities will look behind this statistic to tell the stories of some of those who have died on Britain’s streets. We will tell not just the story of their death, but the story of their life – what they were like as kids, what their dreams were, their hobbies, what people loved about them, what was infuriating. We will also examine what went wrong with their lives, how it impacted on their loved ones, and if anything could have been done differently to prevent their deaths.

As the series develops, we will invite politicians, charities and homelessness organisations to respond to the issues raised. We will also ask readers to offer their own stories and reflections on homelessness. We want the stories we tell to become the fulcrum of a debate about homelessness; to make a difference to a scourge that shames us all.

It is time to stop just passing by.

In Britain today, there are tents everywhere – city centres, railway stations, parks and towpaths. They have come to signify our fractured society. This is the seventh-wealthiest country in the world, where the disparity between rich and poor continues to grow, and where, according to Shelter, 320,000 people are homeless (roughly one in 200 of the population). Last year, it was reported by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism that at least 449 people had died in the UK while homeless in the 12 months up to October 2018.

We meet Aimee’s aunt, Cathy Teese, in a tapas bar in Liverpool. A 45-year-old special-needs teacher, Cathy’s youthfulness belies the tough life she has led. Her drug-addicted father killed himself by setting fire to the family home when she was 11 (thankfully, there was no one else in the house), and her mother was left to bring up four children alone: Stephen, Aimee’s father John, Paul and Cathy.

“Losing our dad hit the four of us in different ways,” she says. “The older two went to drugs, and me and Paul never touched drugs. I’m too scared of them. I’ve seen too much. I’ve instilled that into my girls as well.”

Cathy’s oldest brother, Stephen, died when he was 35. Aimee’s mother, Jackie, who was also dependent on drugs, died aged 29 and was buried alongside Aimee’s brother, Mikey, who died when he was 14 months old.

Cathy apologises for rattling off these tragedies. “I must seem heartless. I can talk about it without emotion these days,” she says. But while Cathy is tough, she is also warm and selfless; a woman who has not just survived, but thrived.

When Aimee was three years old, she was taken into care and fostered. Cathy, who was 17 and pregnant, fought for contact with her niece. The courts granted once a month, which increased to once a week, and she and Aimee became close. Then, when Cathy was 25, social services called out of the blue.

“It was a Friday afternoon. ‘Hiya, are you able to take Aimee tonight?’ It was as quick as that because her relationship with the foster parents had broken down.” Cathy’s daughters, Lydia and Autumn, began sharing a room, and Aimee, who was almost 11, got a room to herself. “She was older. She’d been through a lot more. She had to get the room,” Cathy says. Aimee immediately fitted in. Lydia and Autumn had gained an older sister.

Cathy and Aimee had a special bond. “We’d just lie on the bed and have a conversation. She’d tell me how much she loved me and I’d tell her how much I loved her.” Even as a young teenager, she says, what Aimee wanted most was to be a mum – to nurture and love a child in a way her own mother had never been able to.

“She had a massive, infectious laugh,” Cathy says. “The girls would be upstairs with the Spice Girls on and our Aimee was the worst dancer ever, honest to God! She had no rhythm, but my two girls were brilliant. So I used to take the piss. I’d say: ‘Come on, do the Spice Girls,’ and she’d go: ‘No, no, no, no, go out of the room and I’ll do it,’ but I wouldn’t. I’d be by the door and go: ‘Oh my God!’” Was Aimee upset? “Nooo! We had a right giggle about it.”

But Aimee grew more rebellious. At 14, she started drinking. Often she would have a drink early in the morning and her school would phone Cathy to complain. Aimee would stay out late, and Cathy would tick her off, but Aimee could always talk her round. “She had the gift of the gab. She was really popular. She was funny, she won over everybody.” What made her special, Cathy says, is that she never judged others. “You could have four heads and no legs and she wouldn’t be arsed. She was amazing.”

The drinking got worse. Cathy encouraged Aimee to come out Thai boxing with the rest of the family, but she wouldn’t. When they came back home, they would find that Aimee could have got through five bottles of beer. “She was battling stuff in her own head,” Cathy says. “She talked to me about her mum. She’d say she wished she had what we had as a family.” Even though Cathy treated her like her own, Aimee was conscious that she wasn’t her daughter. “Living with girls who call me Mum, that’s a smack in the face,” Cathy says.

The more Aimee drank, the more worried Cathy became about the influence her niece was having on her own children. “I spoke to social services; it got to the stage where it was too much to cope with.” At 15, Aimee went to live with her grandmother in Deal, Kent. She returned briefly to Cathy’s home, and tried her best. But by then she was also abusing substances. “I had a rule that if you’re drinking and doing drugs, I can’t have you around the house. It’s probably one of my regrets,” Cathy says. Even now, you can still see her weighing it up. “But maybe not, because I didn’t want my girls to see what I’d seen when I was growing up.”

At 17, Aimee was given a council house. In retrospect, Cathy says this was almost as dangerous as providing her with nothing. “It was a proper bloody house, with a dining room and everything. She couldn’t cope with that. The whole street was terrace housing, and it was all bums outside. I remember walking down the street and every house was occupied by young people.” Liverpool’s most vulnerable young people had been provided for, but not supported, given homes to play adults in, doss, get wasted and deal drugs.

Aimee was moved into a flat – smaller, more practical, in a better location. She was almost 20, clean and pregnant. Although she and the baby’s father broke up, she embarked on the happiest, most stable period of her life. “She was fantastic, a natural with babies,” says Cathy. “She didn’t need teaching anything. I’d ask her advice as much as the other way round. At school meetings, she was faultless.” Aimee volunteered as a cleaner in a care home when her daughter, Emily*, was at nursery. At this stage, Cathy and Aimee were more like sisters. Cathy split up with her partner of 22 years, and it was her niece, now 24, she looked to for comfort. “She was the first person I went to. She was just there for me.” They would sit in pyjamas and Aimee would roll cigarettes. “I was off the ciggies so I’d say, ‘Let me just have one’ and she’d be like, ‘No.’” Aimee was reckless herself, but a strict disciplinarian with those she loved.

Everything seemed too good to be true. Then Aimee became involved with an abusive man. She started drinking and taking drugs again, and handed Emily over to another aunt because she couldn’t cope. Before long she had lost her house and was living on the streets. Cathy lost contact with her.

Five years ago, when Cathy was pregnant with her son Earl, she heard Aimee was homeless. “Someone said: ‘Your Aimee’s begging outside Sainsbury’s,’ and I went: ‘Are you sure?’ She said: ‘Yeah, I took a photo of her.’” How did she feel? “Devastated. We’ve lost so many people in our family to drugs. I thought about my mum, who was close to Aimee. I thought, bloody hell, it’s not fair on her.”

A few months later, Aimee turned up for a traumatic reunion. Cathy had just given birth to Earl after a caesarean section, and by now Aimee, who was bisexual, was living with a woman called Marie. “I’d just had a C-section, and I was at home in the bath in terrible pain. In marches Aimee up the stairs into the bathroom. She was pissed as a fart. She was just so overwhelmed with Earl, because she’d had a little brother, Mikey, and Mikey had died. All she kept saying to me while I was pregnant was: ‘I hope it’s a boy, hope it’s a boy.’ And she was just crying and stroking his face. I didn’t want to take that moment away from her.” But she knew she didn’t want Aimee to return in this condition. “I’d just had a baby. I couldn’t have her coming around like this. I was gutted, though. I felt I’d turned my back on her.”

In November 2018, Aimee turned up unannounced at her grandmother’s house and stayed for a couple of weeks. Cathy says Aimee knew her nan, Cathy’s mother, would forgive her anything. But one day Aimee said she was going out for cigarettes, and they never saw her again.

Michelle Langan, the homelessness campaigner who saw Aimee hours before she died, has been listening intently; her charity, the Paper Cup Project, supported Aimee for most of her time on the streets. When Cathy talks of Aimee’s warmth and humour, Langan smiles; she remembers Aimee as a great talker. She never saw her begging, but people would give her money. “A guy I know said to me: ‘I spoke to her the night she died. I chatted to her and gave her a couple of quid to get a drink.’ That’s the kind of person she was.”

Aimee was generous, always guiding outreach workers to homeless people she considered vulnerable. She was less good at looking after herself. Langan says she looked terrible in the last few weeks of her life. Her gorgeous red hair had been ruined. “One day she turned up to see us and I said: ‘What the hell have you done to your hair?’ She said: ‘I don’t want to talk about it.’ It was like somebody had got scissors and chopped it. It was short, just tufts.”

Aimee was sharing her tent with a male partner at the end of her life, and ticked many boxes for street homeless women – a survivor of domestic abuse, a substance and alcohol addict, chaotic family background and vulnerable on many fronts.

Langan says homelessness, and the threat of homelessness, has become much worse in Liverpool in recent years. In May, an average of 86 people used the council’s emergency homeless refuge, Labre House, every night. Last year, more than 5,000 used the council’s Housing Options service, which aims to prevent families from becoming homeless. Langan counts the causes on her fingers – austerity, universal credit, the bedroom tax, plus cuts to mental health, addiction and homelessness services at a time when the need for them is increasing.

Does she think that, with more resources, Aimee might still be alive? “Yes, she could have gone into rehab 20 times, and the 21st time it might have worked for her. At the moment it’s like: this is your one and only chance and if you fuck it up, you don’t get another.”

Cathy is less certain Aimee could have been saved. “Was she let down? Personally I don’t think so. I think she was given the help from a young age all the way through. I think Stephen, my brother who died, was also given a lot of help.”

Why wasn’t she in a hostel, at the very least? Langan says Aimee hated hostels, but that Liverpool is better than most cities in its provision for homeless people. “Liverpool has got shelter available every night,” she says. “We fought for this. Beforehand, all over the country it was just when the temperature was -3C or something you opened up a shelter, so I just kept battering the council about this. In the end, the mayor, Joe Anderson, decided to set up a shelter that was open every single night.”

Labre House is named after the patron saint of homelessness, Benedict Joseph Labre. Unlike many shelters it offers refuge to anybody who is homeless, including those without recourse to public funds – mostly on mats or in sleeping bags in two long dormitories. It’s a start, Langan says, but far from perfect. “We speak to people on the streets and feed that back to the council. I was speaking to one guy and said: ‘Are you going to Labre tonight?’ And he said: ‘I’m a recovering drinker, and if I’m in a room where I can smell drink, that’s it for me.’ And it can be very intimidating for survivors of domestic violence. So it’s not suitable for everybody, but it’s better than nothing. When I asked Aimee about it she’d say: ‘Nah, it’s not for me.’”

When Langan started the Paper Cup Project three years ago, she coaxed and, when necessary, shamed local politicians into walking the streets with her to acknowledge the extent of the homelessness problem. “Joe and I used to fight like cats and dogs. We hated each other.” Why? “Because in the papers he denied Liverpool had a homelessness problem for ages. He was fed misleading facts and figures, and I kept going: ‘This is bullshit.’ He’d say: ‘We’ve only got 12 homeless people,’ because the government said that when you count rough sleepers they have to be bedded down, so if someone is sitting in a doorway, they’re not counted. I got a couple of council cabinet members to come out with us, and they went back to Joe and said: ‘She’s actually right.’ I then had a chat with him. So now we’re on the same page, and that’s great.”

For Langan, homelessness is a political problem. The Labour party made homelessness a priority when it came to power in 1997, and claimed its Rough Sleepers Initiative reduced rough sleeping by around three-quarters. In March this year, the Conservative government promised £46m over the next two years to help get people off the streets (providing 2,600 beds and 750 extra support staff), but Langan is scathing about its efforts. “We shouldn’t have a homelessness problem in 2019. Homeless people don’t have a vote, so the Tory government doesn’t give a shit about them.” Is it incompetence? “No, I think it’s cruelty and greed. We shouldn’t have people sleeping in doorways in a rich country.”

Both she and Cathy call it an uncaring culture. “Society has become callous and cold. It’s me, me, me,” Langan says. Cathy nods. “It’s completely changed,” she says. “Just seeing people mocking each other, saying: ‘I’ve got this, you’ve got nothing.’” They talk about common attitudes to homeless people – be grateful for what you’re given, don’t complain, you are the undeserving poor. “There was a homeless lad we knew who was a vegetarian,” Langan says, “and when people gave him a ham butty he’d be like: ‘No thanks, I’m a vegetarian.’ And some people would be like: ‘Oooh, I tried to give him a butty, and he refused it!’ They’d take offence. I’d be like: ‘Well, did you actually ask him what he wanted?’ Just because you’re homeless doesn’t mean you shouldn’t have a choice about things.”

As we leave, Cathy says she hopes she’s not been too harsh on Aimee. “She didn’t set out to hurt people, she just did along the way. You wouldn’t have met her and gone: ‘She’s a pain in the arse.’ You’d say: ‘Isn’t she a cracking girl?’”

Outside the restaurant we’ve been talking in, two people are bedding down for the night. Both knew Aimee and say she was funny and loud. Mary* tells us she is 17 weeks pregnant and still taking heroin. Moses, a middle-aged man who could pass for elderly, is also an addict. He is filthy, sharp and welcoming. We sit down with them. Moses has a shocking abscess that gnaws deep into a knuckle.

Two young women approach, and one hands over a large pizza box. Moses politely asks what it contains. “Ladies, don’t be offended, but if it’s the remains and it’s cold, it’s better to put it in the bin than give it to me.” The women stare at him, aghast. “Right! Just leave it with him!” screams one, before they stomp off into the night. The box contains the sodden remains of pizza and chips, and a half-eaten chicken leg.

The Whitechapel Centre, Liverpool’s leading homeless and housing charity, is based in a Victorian school that has seen better days. The smell is overpowering – booze, fags and sweat. Outside, men (nearly all the service users here are men) smoke by themselves or in huddles. Inside, clients are being served cooked breakfasts, showering, getting legal advice, benefits help or support with their search for accommodation. One man is having his hair cut.

David Carter, the chief executive of the Whitechapel Centre and Labre House, has worked with homeless people for decades. He measures the crisis in bald statistics. Five years ago, 1,800 people came through the Whitechapel’s doors; last year, it was 4,025. In 2014, the biggest cause of homelessness was relationship breakdown; now it’s debt. “The impact of welfare reforms has had such a deep impact on people’s ability to sustain accommodation,” he says. Few of the people they see are simply homeless – 71% have drug or alcohol addictions, 61% have mental health problems, 50% have escaped or experienced abuse.

The problems are increasingly complex. For example, there are more and more long-term IV substance abusers with amputated limbs needing adapted properties. While the level of need has risen for many clients, austerity, welfare reforms and the economic downturn have all had an impact. “A lot of the preventive services have folded,” Carter says. “So not only do we have more people coming through, but, at the same time, the options for those people have also decreased.” He says the Whitechapel is lucky – the charity gets £2.2m a year from the council to fund its services and its 90 staff. But it’s still peanuts. How much money does he need? Double maybe, he says.

We are joined by Liverpool’s mayor, Joe Anderson, who bombards us with more figures. By next year, Liverpool’s budget will have been slashed by £444m in a decade, or 64% in real terms – more than any other UK city. Anderson sounds like Alexei Sayle, sticks the boot into political adversaries with the same relish and has a fondness for the F-word. “We are spending £50m on housing benefit, which mainly goes to the private sector. Is that not fucking madness? If you built more social housing you wouldn’t be paying that housing benefit bill. It’s absolutely crazy and incompetent.”

We ask Anderson the official number of rough sleepers in Liverpool city centre. He looks at Carter. “What’s your version?” Carter laughs. As Langan said the other night, there are many ways of recording the statistics.

“Each month, our outreach workers record every homeless person they see,” Carter says. “Last month, we saw 76 people bedded down. It has been pretty stable over the past 12 months. Of them, I would say we got 55 into new or existing accommodation.”

Both men say there are homeless fakes – people who come into the city to beg, to feed addictions or just make a bit of cash. But they are a small minority. Their priority is to get the genuinely homeless off the street. “The first rule is: ‘No second night out.’ When we identify someone sleeping rough, we have them accommodated the following day,” Anderson says. Another motto is: “There’s always room inside” – and Anderson insists there is, now that Labre House has opened.

But the fact remains that both Aimee Teese and Richard Kehoe were street homeless when they died. How does Anderson feel about them dying within three months of each other in tents on the streets of his city? “Absolute anger. When we talk about eradicating homelessness, it’s not just about moving them out of tents, it’s not just about finding them accommodation, it’s about finding them a job, it’s about changing their lifestyle.” Aimee was imprisoned in the run-up to Christmas 2018, just after disappearing from her grandmother’s home, and Anderson says he was angry when he heard that she had been released, “still addicted, with all the demons she still had to face – and we weren’t told about it. And the worst thing is she stayed a bit out of the city centre in a grim area next to a housing estate that we’ve got boarded up. If we’d known about it, Whitechapel could have done something. She might not have died.”

Who is Anderson most angry with? “The system. Everybody. Me!” How has he messed up? “I feel guilty because I manage a city council, a system, that is not joined up. It hurts. I remember David Cameron coming in and talking about the ‘big society’ – and it’s the fucking broken society. That’s what we’re dealing with. And you can’t cut and cut and cut, and not accept consequences. Aimee’s’s death is a mixture of lack of joined-up thinking and cuts. If we’d had more public health workers connecting into probation, connecting into the Prison Service, we would have been told about her.”

It is certainly true that people are slipping through some very leaky nets. But it’s not correct that nobody knew Aimee was living in a tent. After all, Langan visited her on the night she died.

Why does Anderson believe that getting rid of tents is the answer? Many homeless people say a tent gives them privacy and a degree of warmth. Anderson insists that is the wrong starting point – there is no reason for anybody to be homeless in Liverpool; every night there are spare rooms at the YMCA or Labre House. “There’s no reason for anybody to sleep on the streets. If people choose to live on the streets, because they have mental health issues, for instance, then we’ll take that into consideration. But if somebody’s in a tent and they’re jacking up and doing stuff to themselves that no one can see, how are we going to know?”

Carter and Anderson say that much of the city’s homeless drug dealing is done from within tents. The bottom line, Anderson says, is that tents hide illegal activity and vulnerable people who need support. When he announced the zero-tolerance policy on tents, people were sceptical – and worse. “I got a lot of shit on Twitter, as we usually do. People say we’re not doing enough. The city’s not doing enough. I get it all the time. People want to blame somebody for the problems we have in the city. They want to get angry with somebody, so they get angry with me.”

The mayor has a reputation for grandstanding, but there is no questioning his desire to tackle the crisis. We mention pregnant Mary, who we met on the streets the previous night. Anderson and Carter look at each other. “Ah. We know her very, very well,” Anderson says. “And you know why she won’t accept accommodation? She’s had children before, she’s a drug user and we have a child protection order on the baby. We have issues with the father of the baby, her partner. She wants to live with him, and the order stops that happening. There’s much more to your story.” His version is consistent with what Mary told us – she admitted she was still taking heroin. Anderson says, as with Aimee Teese, it would be pointless to address her housing situation without tackling her addiction issues.

It is late June, almost six months since Aimee died and three months since Anderson announced he was going to remove tents from the streets of Liverpool. We meet up with Langan and Cathy to distribute food and clothes to homeless people. Cathy now volunteers for the Paper Cup Project as an outreach worker. She says it has given her a new sense of purpose.

Anderson is not the only public official who has been clearing tents from the streets. The Guardian has just revealed that the number of homeless camps forcibly removed by councils across the UK has more than trebled in four years (from 72 in 2014 to 254 last year). An encampment was defined as a location where one or more homeless people were living on private or public land. The Guardian also revealed there were 1,241 complaints to councils last year regarding “tent cities” and that some councils (including Brighton and East Dorset) charge for the return of seized tents.

At Aimee’s inquest in April, the coroner recorded that she had been found dead in her tent in the back yard of a disused factory. It was revealed she had a medical history of hepatitis C, and drug and alcohol addiction. In the hours before her death she had smoked crack cocaine with her partner and used heroin “within the range of a fatal dose”. She was found by her partner, who returned to the tent after a disagreement with her. Cathy says her niece’s death has turned her life upside down. “It’s split me and my partner up. He’s a bit younger than I am, and he didn’t understand what I was going through. I kept everything in on myself. And I blame myself a lot as well. I took a lot of the guilt because I shouldn’t have said what I said to her.” What does she mean? “I said: ‘With drink and drugs, I can’t have you around here.’” She is becoming tearful. “But I didn’t think she would ever be homeless and I didn’t think she’d ever die.”

There isn’t a day Cathy doesn’t think about Aimee. But one huge positive has come out of all this. She whips a photo out of her wallet. “That’s me, Aimee and her daughter Emily when she was a baby.” Cathy had been close to Emily, who is now 10 and still living with another aunt. Four years after losing contact with each other, she and Emily are rebuilding their relationship. Cathy is overjoyed to have her back in her life. “I had her for the day a few weeks ago,” she says. “We’re just getting to know each other again and we had an absolute ball. We went swimming and went to Anfield to watch the match. The kids love that they’ve got a new cousin.”

Cathy still hasn’t come to terms with Aimee’s death, even though she half expected it. “I didn’t think it would come to this at 30. It sounds cold, but I thought she would die from drugs and things, but that she would be older.”

It was Cathy who identified the body. What shocked her most was Aimee’s hair. “She had gorgeous hair. She was so proud of it – long and dyed red. And when I went to see her, it was all chopped off.”

She was left alone with Aimee’s body. Cathy says it took her ages to say anything, then she let rip. “I gave her a bollocking. I gave her a really good bollocking. I told her off like a proper parent. I said: ‘I’m totally fucking pissed off with you.’ I was just kind of ranting. It felt good.” She is laughing and crying as she says this. “And then when I finished bollocking her, I told her I loved her.”

Indicated names (*) have been changed.

In the UK, Samaritans can be contacted on 116 123 or email jo@samaritans.org. If you are worried about becoming homeless, contact the housing department of your local authority to fill in a homeless application. You can use the Gov.uk website to find your local council

Follow Guardian Cities on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram to join the discussion, catch up on our best stories or sign up for our weekly newsletter