How the taboo of single mothers created an underclass of abused children.

The beating of a 4-year-old boy on Christmas Eve went on through the night. Covered with bruises and having suffered catastrophic internal bleeding, he was pronounced dead at a hospital. Soon after, his mother and her two boyfriends were arrested.

While the news of the child’s death sparked outrage and horror in Japan’s media, Orie Ikeda, a single mother of two, says she can understand how such a brutal assault occurred in Minoh, the affluent dormitory town near where she lives.

“It could have been me,” she said quietly. “I didn’t abuse my children only because I was lucky.”

Orie Ikeda

Photographer: Shiho Fukada/Bloomberg

Ikeda managed to get on a government training course that helped her secure one of the lowest-paid jobs in Japan: Looking after the nation’s growing cohorts of elderly.

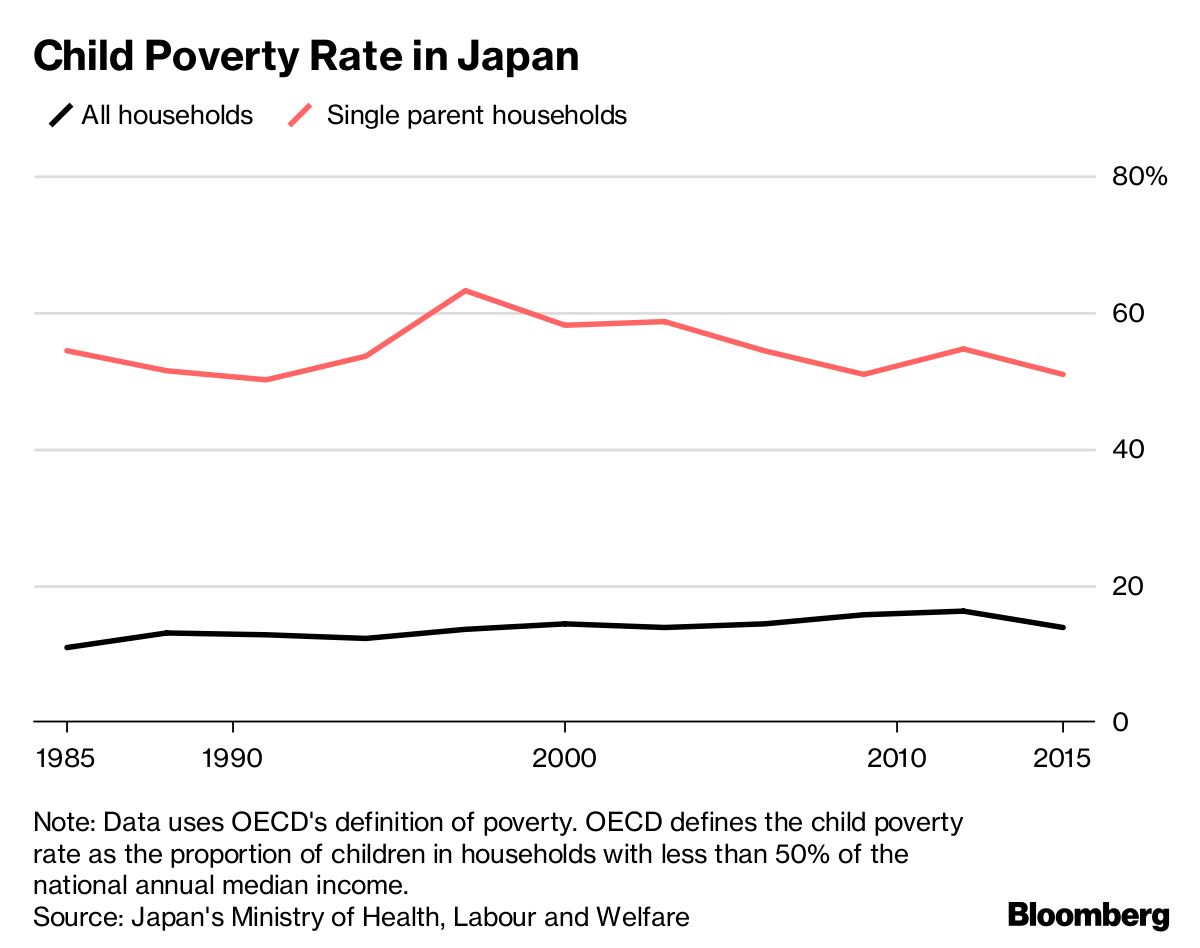

Most single mothers in Japan exist on less than half the national median income, the poverty line defined by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Their children are, on average, poorer, less educated and have fewer prospects — an underclass in a wealthy and aging nation that can ill-afford to lose a significant chunk of its future workforce. One in every seven children in Japan experiences poverty.

Failing to address that will cost Japan 2.9 trillion yen ($26.3 billion) in lost incomes and 1.1 trillion yen in lost taxes and social security payments for each year of children at school, according to the Nippon Foundation in Tokyo. The estimate calculates the impact over the future working life of 15-year-olds.

It’s also a lost opportunity for a country that desperately needs as many young, highly skilled workers as it can get.

Even after decades of stagnation in the shadow of China’s economic rise, Japan is still among the 10 wealthiest nations with more than 10 million people in terms of GDP per capita.

But almost none of that wealth trickles down to Japan’s single mothers. Fewer than half of them receive alimony, and even if they can get a job, the odds are stacked against them. Working women earn roughly 30 percent less than men doing a similar job in Japan, and about 60 percent of women who work hold part-time, contract or temporary jobs where pay is lower and benefits can be non-existent.

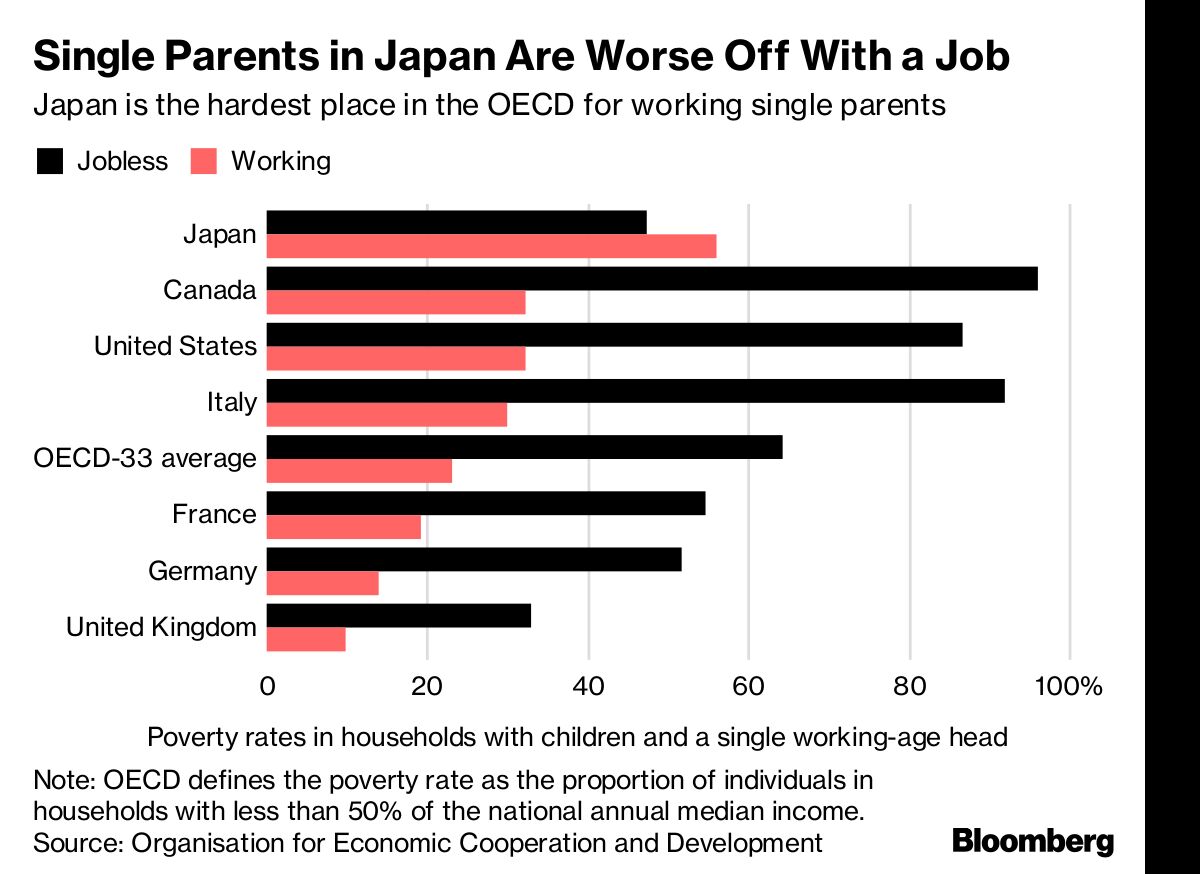

Yet while Japan’s overall population is declining, the number of single-mother households in the country rose by about 50 percent to 712,000 between 1992 and 2016, according to the labor ministry. The child poverty rate for working single-parent households in Japan stood at 56 percent, the highest among OECD nations, compared with 32 percent in the U.S.

Those that get alimony or child support from their ex-spouse or live with their parents are the lucky ones. In Japan, single parents are more likely to live in poverty with a job than without, according to the OECD.

“Your choices become very narrow when you don’t have money,” said Ikeda, 52. “You must put up with a lot of small things.”

Most Single Moms in Japan Live in Poverty

What made the Christmas Day death especially shocking for Japan is that Minoh is the last place where most people would expect it to happen.

Mayor Tetsuro Kurata, 44, had tried to make the city a national model of child protection, installing hundreds of surveillance cameras along the roads children use to go to school and parks, and analyzing a database with the assistance of social groups that would monitor children’s progress at school and home for any sign of trouble.

Then, Kurata got the call just before dawn on Dec. 25.

“It was unbearable; it’s Christmas,” said Kurata, who has three sons, the youngest of whom is also 4. “We couldn’t stop it even though we were involved. What were we doing?”

The town of Minoh, near Osaka city.

Photographer: Shiho Fukada/Bloomberg

Visitors flock to Minoh from nearby Osaka to hike in its famous park, with its picture-postcard Japanese bridge in a wooded glade below a waterfall. Single-family homes dot rolling streets shaded with maple trees.

The crime scene itself is in a freshly painted white apartment complex on a small hill, where the smell of cut grass wafts in the air and fallen leaves are neatly piled. A nearby house holds piano lessons for children.

Behind that facade, the city’s report of the crime tells a different story, one of hardship, brutality and a struggle to keep up appearances in public. The single mother of two boys was sick and looking for a part-time job. When she found one at a supermarket, she couldn’t start because she didn’t have childcare during Sunday shifts.

She had already been reported for possible neglect in the town where she used to live. She turned up at her boys’ school with two men, who she told staff were cousins. Two weeks before the older son was killed, a teacher visiting the mother’s home noticed a bruise on the left cheek of the younger son.

“The mother was also a victim,” said Tsuyoshi Watari, who runs Atto School, a nonprofit organization in Minoh that helps students from single-parent households. “I grew up with one parent and my mother was very strong. But I had a hard time and walked a tightrope to finish college.”

Left: Atto School’s Tsuyoshi Watari, Right: A tutoring session in progress.

Photographer: Shiho Fukada/Bloomberg

The reasons why Japan’s single parents and their children have slipped through the net are not just about money.

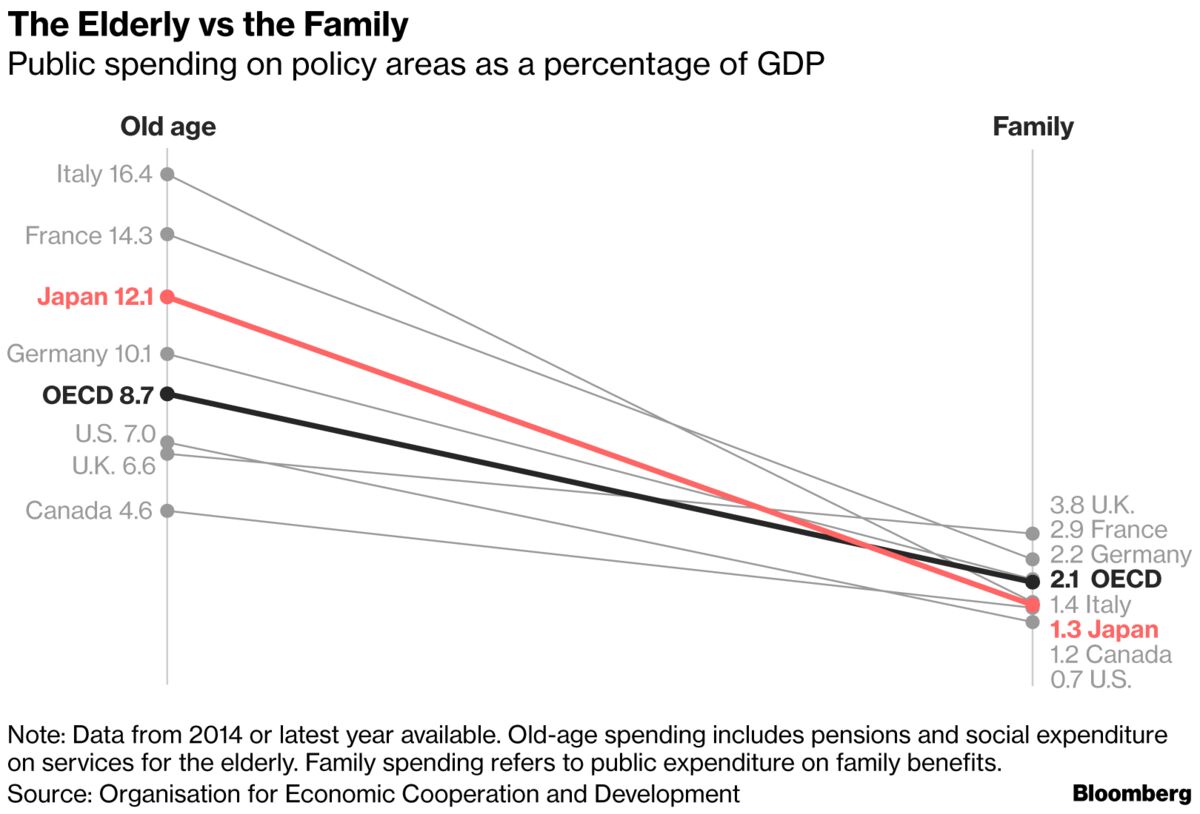

Much has to do with the twin taboos of being a divorced mother and being poor. In addition, public spending has favored the old — an increasing proportion of the electorate. Work prospects for single parents have also been eroded — years of economic stagnation hollowed out Japan’s once-ubiquitous salaried middle class, replacing many positions with low-paying, part-time or contract jobs.

“It’s wrong,” said Ikeda, who has struggled to secure childcare while serving senior citizens whose costs are largely covered by a public insurance program. “It’s extremely difficult to raise children.”

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has encouraged women to “shine” by balancing child rearing with a job, and official female labor participation rates have risen, partly due to the increase in the number of part-time positions.

Ikeda folds laundry in her home.

Photographer: Shiho Fukada/Bloomberg

For one single mother in Minoh, Abe’s challenge seems more like a dream.

Speaking on condition of anonymity because of fear about her ex-husband, she said that, for her, “shining” would be simply to live a normal life. She said she felt she was at the bottom of society and her priority was just to be able to feed her child.

She works two part-time jobs, as a receptionist at a local clinic and a clerk at a store. She said other single mothers she knows have to work more.

Masaji Matsuyama, minister of demographic challenges, says the plight of children has eased under Abe’s premiership since late 2012. Child poverty fell to 13.9 percent from 16.3 percent between 2012 and 2015, and for single-parent households dropped to 50.8 percent from 54.6 percent, according to the labor ministry.

“Child poverty is now being eliminated,” said Matsuyama, a 59-year-old father of four. He said the government is creating “all-generation social programs,” though he agreed more efforts are needed to help single parents.

Abe passed a law that took effect in 2014 to tackle child poverty so that “their upbringings won’t dictate their future.”

The prime minister also plans to raise the sales tax in 2019 to help fund social projects, including free preschools. But the government has to service the world’s largest national debt and the bulk of public service spending goes to the elderly. The goal of a primary budget surplus has been pushed back five years to fiscal 2025.

Noriko Yamano, a professor at Osaka Prefecture University who serves on the government’s expert panel on child poverty, said there’s little evidence that the government’s policies are the cause of the dip in child poverty, because it funds projects without monitoring their effectiveness and typically doesn’t set proper targets.

A failure to help disadvantaged children has major repercussions for Japan’s future because of the burden on a shrinking young workforce to look after a growing population of elderly, according to Makiko Nakamuro, an associate professor at Keio University in Tokyo, who specializes in the economics of education.

“People are starting to live to 100,” she said. “Today’s children will have to live in such an era. Seriously, it’s impossible.”

In some areas, it has been left to charities to try to battle child poverty and abuse, such as the one started by Daiwa Securities Group Inc. last year.

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has encouraged women to “shine” by balancing child rearing with a job, and official female labor participation rates have risen, partly due to the increase in the number of part-time positions.

Photographer: Shiho Fukada/Bloomberg

“A brokerage symbolizes capitalism,” Chief Executive Officer Seiji Nakata said. “Capitalism and the market economy create inequality. I don’t think all of child impoverishment stems from inequality, but it’s one of the factors.”

Nakata first got involved years ago when he discovered to his surprise an orphanage next to his daughter’s preschool. He began sending Christmas presents to the children.

Japan’s orphanages have become the country’s asylums for abused children. Many were set up after the war for the street children who had lost parents. Now, about 60 percent of the kids they take were abused or neglected, according to the welfare ministry.

At the House of Hope in Katsushika Ward in eastern Tokyo, a handwritten message is on display near the entrance from a visit by the prime minister. It simply says, “Hope. April 4, 2014. Shinzo Abe.”

But the abuse and disadvantages mean many of the children from Japan’s orphanages have dimmer prospects. At 18, when they have to leave, only 12 percent go to college, compared with 52 percent of high school graduates.

“Some can set goals, but can’t work hard to reach them,” said Ai Makieda, 25, an instructor at the House of Hope, who was raised at an orphanage after her unmarried and jobless mother neglected her. She won a scholarship from Goldman Sachs Group Inc. which enabled her to finish college and she hopes that one day she will get married and raise her own children.

“I wasn’t isolated,” she said. “That was big.”

Goldman’s involvement sprang from a charity event when Shigeki Kiritani took Christmas gifts to an orphanage. He began helping fund some of the children to go to college. Kiritani, president of Goldman Sachs Asset Management Co. in Japan, is one of a group of partners who sponsor the scholarship program.

“In investment terms, you will have a compounding effect for decades,” he said. “They have a long future ahead of them.”

Stringent privacy laws and a culture of keeping up appearances make it hard to spot much of the poverty in Japan. In Bunkyo Ward in central Tokyo, another affluent neighborhood that is home to the University of Tokyo and the Tokyo Dome baseball stadium, a joint project between government and local groups identifies poor families and covertly provides them with some free groceries so that neighbors don’t know. Seven cases of domestic violence have been found via the program. More than half of the project’s users are single-parent households.

Free grocery provisions are packed in Tokyo for families in need.

Photographer: Shiho Fukada/Bloomberg

“People are afraid to be known as poor households and that fear is increasing their stress,” said Hironobu Narisawa, the ward’s mayor. “We want to support them in a closed, invisible way so that they won’t be stigmatized.”

Out of 1,447 child abuse cases in the year through March 2004, 32 percent occurred in single-parent households and 31 percent happened in households experiencing economic difficulties, according to a report by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government.

In Minoh, memories of the crime are already fading now that police cars, media crews and Santa socks put on the family’s mail box are all gone.

“It’s as if nothing happened,” said Michiko Matsui, who has run a beauty salon nearby for more than 40 years and had watched the mother and her children play in front of her shop. “You forget. It can’t be helped.”

One person who hasn’t forgotten is Kurata, the mayor, who has vowed never to let it happen again.

“That’s the only way to atone for the boy,” he said. “It won’t be enough, but that’s the only thing we can do.”

(Adds information on program to identify poor families. )