Whistleblower describes how firm linked to former Trump adviser Steve Bannon compiled user data to target American voters

• How Cambridge Analytica’s algorithms turned ‘likes’ into a political tool

The data analytics firm that worked with Donald Trump’s election team and the winning Brexit campaign harvested millions of Facebook profiles of US voters, in one of the tech giant’s biggest ever data breaches, and used them to build a powerful software program to predict and influence choices at the ballot box.

A whistleblower has revealed to the Observer how Cambridge Analytica – a company owned by the hedge fund billionaire Robert Mercer, and headed at the time by Trump’s key adviser Steve Bannon – used personal information taken without authorisation in early 2014 to build a system that could profile individual US voters, in order to target them with personalised political advertisements.

Christopher Wylie, who worked with a Cambridge University academic to obtain the data, told the Observer: “We exploited Facebook to harvest millions of people’s profiles. And built models to exploit what we knew about them and target their inner demons. That was the basis the entire company was built on.”

Documents seen by the Observer, and confirmed by a Facebook statement, show that by late 2015 the company had found out that information had been harvested on an unprecedented scale. However, at the time it failed to alert users and took only limited steps to recover and secure the private information of more than 50 million individuals.

Profile

Cambridge Analytica: the key players

Alexander Nix, CEO

An Old Etonian with a degree from Manchester University, Nix, 42, worked as a financial analyst in Mexico and the UK before joining SCL, a strategic communications firm, in 2003. From 2007 he took over the company’s elections division, and claims to have worked on 260 campaigns globally. He set up Cambridge Analytica to work in America, with investment from Robert Mercer.

Aleksandr Kogan, data miner

Aleksandr Kogan was born in Moldova and lived in Moscow until the age of seven, then moved with his family to the US, where he became a naturalised citizen. He studied at the University of California, Berkeley, and got his PhD at the University of Hong Kong before joining Cambridge as a lecturer in psychology and expert in social media psychometrics. He set up Global Science Research (GSR) to carry out CA’s data research. While at Cambridge he accepted a position at St Petersburg State University, and also took Russian government grants for research. He changed his name to Spectre when he married, but later reverted to Kogan.

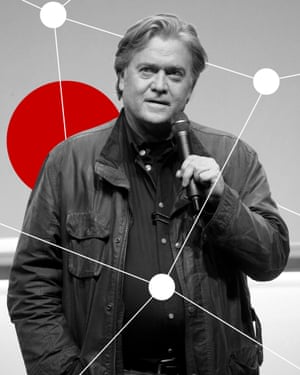

Steve Bannon, former board member

A former investment banker turned “alt-right” media svengali, Steve Bannon was boss at website Breitbart when he met Christopher Wylie and Nix and advised Robert Mercer to invest in political data research by setting up CA. In August 2016 he became Donald Trump’s campaign CEO. Bannon encouraged the reality TV star to embrace the “populist, economic nationalist” agenda that would carry him into the White House. That earned Bannon the post of chief strategist to the president and for a while he was arguably the second most powerful man in America. By August 2017 his relationship with Trump had soured and he was out.

Robert Mercer, investor

Robert Mercer, 71, is a computer scientist and hedge fund billionaire, who used his fortune to become one of the most influential men in US politics as a top Republican donor. An AI expert, he made a fortune with quantitative trading pioneers Renaissance Technologies, then built a $60m war chest to back conservative causes by using an offshore investment vehicle to avoid US tax.

Rebekah Mercer, investor

Rebekah Mercer has a maths degree from Stanford, and worked as a trader, but her influence comes primarily from her father’s billions. The fortysomething, the second of Mercer’s three daughters, heads up the family foundation which channels money to rightwing groups. The conservative mega‑donors backed Breitbart, Bannon and, most influentially, poured millions into Trump’s presidential campaign.

The New York Times is reporting that copies of the data harvested for Cambridge Analytica could still be found online; its reporting team had viewed some of the raw data.

The data was collected through an app called thisisyourdigitallife, built by academic Aleksandr Kogan, separately from his work at Cambridge University. Through his company Global Science Research (GSR), in collaboration with Cambridge Analytica, hundreds of thousands of users were paid to take a personality test and agreed to have their data collected for academic use.

However, the app also collected the information of the test-takers’ Facebook friends, leading to the accumulation of a data pool tens of millions-strong. Facebook’s “platform policy” allowed only collection of friends’ data to improve user experience in the app and barred it being sold on or used for advertising. The discovery of the unprecedented data harvesting, and the use to which it was put, raises urgent new questions about Facebook’s role in targeting voters in the US presidential election. It comes only weeks after indictments of 13 Russians by the special counsel Robert Mueller which stated they had used the platform to perpetrate “information warfare” against the US.

Cambridge Analytica and Facebook are one focus of an inquiry into data and politics by the British Information Commissioner’s Office. Separately, the Electoral Commission is also investigating what role Cambridge Analytica played in the EU referendum.

“We are investigating the circumstances in which Facebook data may have been illegally acquired and used,” said the information commissioner Elizabeth Denham. “It’s part of our ongoing investigation into the use of data analytics for political purposes which was launched to consider how political parties and campaigns, data analytics companies and social media platforms in the UK are using and analysing people’s personal information to micro-target voters.”

On Friday, four days after the Observer sought comment for this story, but more than two years after the data breach was first reported, Facebook announced that it was suspending Cambridge Analytica and Kogan from the platform, pending further information over misuse of data. Separately, Facebook’s external lawyers warned the Observer it was making “false and defamatory” allegations, and reserved Facebook’s legal position.

The revelations provoked widespread outrage. The Massachusetts Attorney General Maura Healey announced that the state would be launching an investigation. “Residents deserve answers immediately from Facebook and Cambridge Analytica,” she said on Twitter.

The Democratic senator Mark Warner said the harvesting of data on such a vast scale for political targeting underlined the need for Congress to improve controls. He has proposed an Honest Ads Act to regulate online political advertising the same way as television, radio and print. “This story is more evidence that the online political advertising market is essentially the Wild West. Whether it’s allowing Russians to purchase political ads, or extensive micro-targeting based on ill-gotten user data, it’s clear that, left unregulated, this market will continue to be prone to deception and lacking in transparency,” he said.

Last month both Facebook and the CEO of Cambridge Analytica, Alexander Nix, told a parliamentary inquiry on fake news: that the company did not have or use private Facebook data.

Simon Milner, Facebook’s UK policy director, when asked if Cambridge Analytica had Facebook data, told MPs: “They may have lots of data but it will not be Facebook user data. It may be data about people who are on Facebook that they have gathered themselves, but it is not data that we have provided.”

Cambridge Analytica’s chief executive, Alexander Nix, told the inquiry: “We do not work with Facebook data and we do not have Facebook data.”

Wylie, a Canadian data analytics expert who worked with Cambridge Analytica and Kogan to devise and implement the scheme, showed a dossier of evidence about the data misuse to the Observer which appears to raise questions about their testimony. He has passed it to the National Crime Agency’s cybercrime unit and the Information Commissioner’s Office. It includes emails, invoices, contracts and bank transfers that reveal more than 50 million profiles – mostly belonging to registered US voters – were harvested from the site in one of the largest-ever breaches of Facebook data. Facebook on Friday said that it was also suspending Wylie from accessing the platform while it carried out its investigation, despite his role as a whistleblower.

At the time of the data breach, Wylie was a Cambridge Analytica employee, but Facebook described him as working for Eunoia Technologies, a firm he set up on his own after leaving his former employer in late 2014.

The evidence Wylie supplied to UK and US authorities includes a letter from Facebook’s own lawyers sent to him in August 2016, asking him to destroy any data he held that had been collected by GSR, the company set up by Kogan to harvest the profiles.

That legal letter was sent several months after the Guardian first reported the breach and days before it was officially announced that Bannon was taking over as campaign manager for Trump and bringing Cambridge Analytica with him.

“Because this data was obtained and used without permission, and because GSR was not authorised to share or sell it to you, it cannot be used legitimately in the future and must be deleted immediately,” the letter said.

Facebook did not pursue a response when the letter initially went unanswered for weeks because Wylie was travelling, nor did it follow up with forensic checks on his computers or storage, he said.

“That to me was the most astonishing thing. They waited two years and did absolutely nothing to check that the data was deleted. All they asked me to do was tick a box on a form and post it back.”

Paul-Olivier Dehaye, a data protection specialist, who spearheaded the investigative efforts into the tech giant, said: “Facebook has denied and denied and denied this. It has misled MPs and congressional investigators and it’s failed in its duties to respect the law.

“It has a legal obligation to inform regulators and individuals about this data breach, and it hasn’t. It’s failed time and time again to be open and transparent.”

A majority of American states have laws requiring notification in some cases of data breach, including California, where Facebook is based.

Facebook denies that the harvesting of tens of millions of profiles by GSR and Cambridge Analytica was a data breach. It said in a statement that Kogan “gained access to this information in a legitimate way and through the proper channels” but “did not subsequently abide by our rules” because he passed the information on to third parties.

Facebook said it removed the app in 2015 and required certification from everyone with copies that the data had been destroyed, although the letter to Wylie did not arrive until the second half of 2016. “We are committed to vigorously enforcing our policies to protect people’s information. We will take whatever steps are required to see that this happens,” Paul Grewal, Facebook’s vice-president, said in a statement. The company is now investigating reports that not all data had been deleted.

Kogan, who has previously unreported links to a Russian university and took Russian grants for research, had a licence from Facebook to collect profile data, but it was for research purposes only. So when he hoovered up information for the commercial venture, he was violating the company’s terms. Kogan maintains everything he did was legal, and says he had a “close working relationship” with Facebook, which had granted him permission for his apps.

Quick guide

How the story unfolded

In December 2016, while researching the US presidential election, Carole Cadwalladr came across data analytics company Cambridge Analytica, whose secretive manner and chequered track record belied its bland, academic-sounding name.

Her initial investigations uncovered the role of American billionaire Robert Mercer in the US election campaign: his strategic “war” on mainstream media and his political campaign funding, some apparently linked to Brexit.

She found the first indications that Cambridge Analytica might have used data processing methods that breached the Data Protection Act. That article prompted Britain’s Electoral Commission and the Information Commissioner’s Office to launch investigations whose remits include Cambridge Analytica’s use of data and its possible links to the Brexit referendum. These investigations are still continuing, as is a wider ICO inquiry into the use of data in politics.

While chasing the details and ramifications of complex manipulation of both data and funding law, Cadwalladr came under increasing attacks, both online and professionally, from key players.

The Leave.EU campaign tweeted a doctored video that showed her being violently assaulted, and the Russian embassy wrote to the Observer to complain that her reporting was a “textbook example of bad journalism”.

But the growing profile of her reports also gave whistleblowers confidence that they could trust her to not only understand their stories, but retell them clearly for a wide audience.

Her network of sources and contacts grew to include not only former employees who regretted their work but academics, lawyers and others concerned about the impact on democracy of tactics employed by Cambridge Analytica and associates.

Cambridge Analytica is now the subject of special prosecutor Robert Mueller’s probing of the company’s role in Donald Trump’s presidential election campaign. Investigations in the UK also remain live.

The Observer has seen a contract dated 4 June 2014, which confirms SCL, an affiliate of Cambridge Analytica, entered into a commercial arrangement with GSR, entirely premised on harvesting and processing Facebook data. Cambridge Analytica spent nearly $1m on data collection, which yielded more than 50 million individual profiles that could be matched to electoral rolls. It then used the test results and Facebook data to build an algorithm that could analyse individual Facebook profiles and determine personality traits linked to voting behaviour.

The algorithm and database together made a powerful political tool. It allowed a campaign to identify possible swing voters and craft messages more likely to resonate.

“The ultimate product of the training set is creating a ‘gold standard’ of understanding personality from Facebook profile information,” the contract specifies. It promises to create a database of 2 million “matched” profiles, identifiable and tied to electoral registers, across 11 states, but with room to expand much further.

At the time, more than 50 million profiles represented around a third of active North American Facebook users, and nearly a quarter of potential US voters. Yet when asked by MPs if any of his firm’s data had come from GSR, Nix said: “We had a relationship with GSR. They did some research for us back in 2014. That research proved to be fruitless and so the answer is no.”

Cambridge Analytica said that its contract with GSR stipulated that Kogan should seek informed consent for data collection and it had no reason to believe he would not.

GSR was “led by a seemingly reputable academic at an internationally renowned institution who made explicit contractual commitments to us regarding its legal authority to license data to SCL Elections”, a company spokesman said.

SCL Elections, an affiliate, worked with Facebook over the period to ensure it was satisfied no terms had been “knowingly breached” and provided a signed statement that all data and derivatives had been deleted, he said. Cambridge Analytica also said none of the data was used in the 2016 presidential election.

Steve Bannon’s lawyer said he had no comment because his client “knows nothing about the claims being asserted”. He added: “The first Mr Bannon heard of these reports was from media inquiries in the past few days.” He directed inquires to Nix.

Since you’re here …

… we have a small favour to ask. More people are reading the Guardian than ever but advertising revenues across the media are falling fast. And unlike many news organisations, we haven’t put up a paywall – we want to keep our journalism as open as we can. So you can see why we need to ask for your help. The Guardian’s independent, investigative journalism takes a lot of time, money and hard work to produce. But we do it because we believe our perspective matters – because it might well be your perspective, too.

I appreciate there not being a paywall: it is more democratic for the media to be available for all and not a commodity to be purchased by a few. I’m happy to make a contribution so others with less means still have access to information. Thomasine F-R.

If everyone who reads our reporting, who likes it, helps fund it, our future would be much more secure. For as little as $1, you can support the Guardian – and it only takes a minute. Thank you.