Humanity’s food security is at far more risk than you realize.

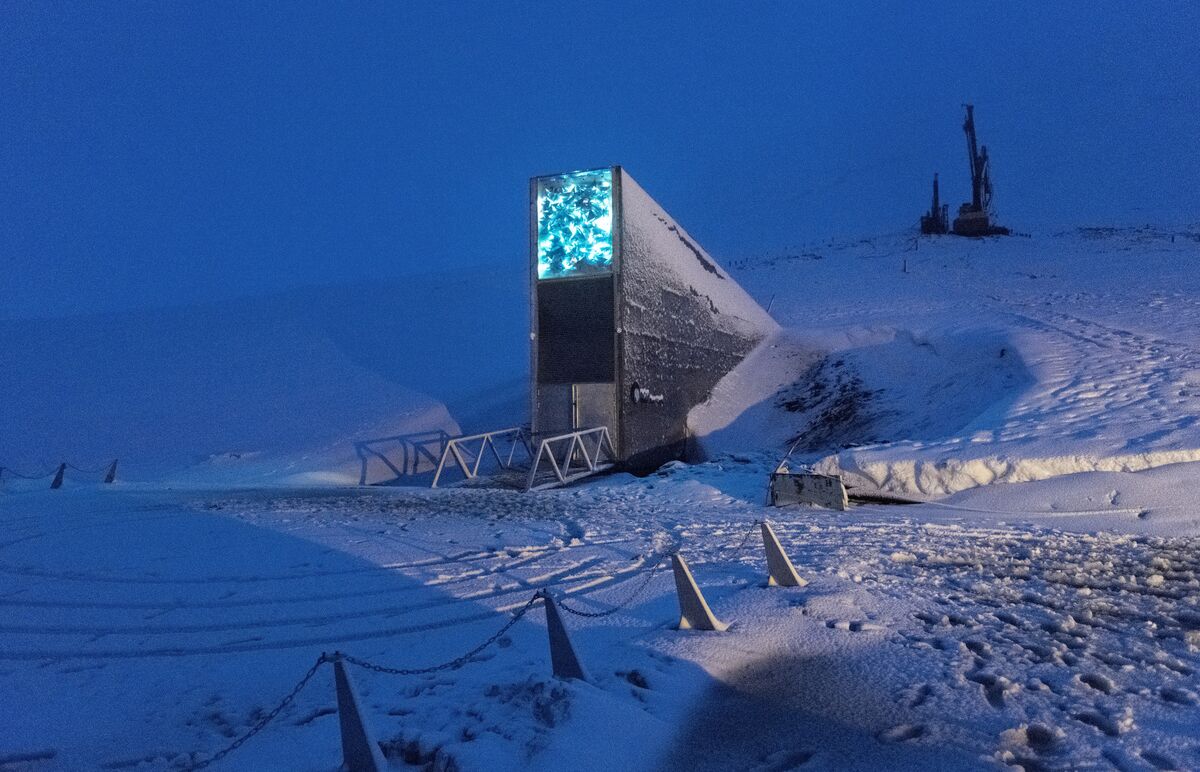

Snow surrounds the entrance to the Svalbard Global Seed Vault in Svalbard.

Photographer: Ivar Kvaal for Bloomberg Businessweek

On this winter day, the world was upside down: it was raining in the Arctic Circle and snowing in Rome.

The contradiction was not lost on those gathered at the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, located near the top of the world. The scientists, activists, executives and government officials were in Longyearbyen, to mark the 10-year anniversary of what has become known as the Doomsday Vault, which stores seeds of the world’s most important crops deep in a mountain against the apocalyptic consequences of climate change and war.

The challenge they’re facing now is that the climate is changing far quicker than they’d imagined. The facility sprung a leak last year after construction had failed to take into account that the permafrost could melt. Norway is now spending about $20 million to secure and improve the facility. But it’s not just the building.

An official passes boxes of seeds inside the Svalbard Global Seed Vault.

Photographer: Ivar Kvaal for Bloomberg Businessweek

“Biodiversity is the building block to develop new plants and because of climate change we’re in a terrible need to quickly develop new varieties,” said Aaslaug Marie Haga, executive director of Crop Trust, a group established to support gene banks. “The climate is changing quicker than the plants can handle.”

Svalbard is the farthest north one can travel commercially, about an 1 1/2 hour flight from northern Norway. The vault is about a 10 minute drive from town, past a coal-fired power plant and up a winding two-lane road. Unless armed with a high-caliber rifle, driving is essential, since leaving town also means venturing into polar bear country. The site’s entrance, not far from the abandoned coal mine that served as the first Nordic seed vault, shines at night like a green beacon, lit up by an artwork of fiber optics, steel and glass called Perpetual Repercussion.

The seeds are kept at minus 18 centigrade (-4 Fahrenheit) more than 100 meters into the mountain behind six steel doors. And in an ideal world, the vault would never have to be used. It’s meant to back up the plant gene banks around the world, organized under the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture.

But many of these facilities are vulnerable. One withdrawal from Svalbard has already been made by the group that ran the seed bank in Aleppo, Syria.

The vault is run by NordGen, the Nordic gene bank. A total of 74 institutes globally have deposits, and only those that send seeds have access. One notable exception is China, which has not signed the treaty, and is creating its own seed and gene banks outside the international cooperation.

Participants say the real fight to preserve biodiversity is at the local level. Crop Trust is seeking to build an $850 million fund to finance its efforts, a long way to go from its current level of $285 million. Its largest donors are the U.S., Germany and Norway, but it’s now looking more to private business for funding.

“We have to be prepared for the unknown,” Jon Georg Dale, Norway’s food and agriculture minister, said in his hotel in Longyearbyen, where he was stuck after canceling a snow-scooter trip because of the thaw gripping the Arctic.

A children’s seesaw sits surrounded by melting snow in Svalbard.

Photographer: Ivar Kvaal for Bloomberg Businessweek

Participants at the conference say (the Trump administration’s climate skepticism notwithstanding) that there have been no signs the U.S. will abandon its commitments. Some joked that perhaps the new administration just hadn’t noticed it yet.

Businesses are becoming more aware of the problems of losing biodiversity, according to Ann Tutwiler, a former Obama-administration official who’s now head of Bioversity International, a global research group backed by more than 50 governments.

“The narrative of the 20th century was that we have to produce more food and that was all about a very narrow range of crops,” said Tutwiler. “Now because we have other issues we are trying to solve, such as climate and nutrition there’s a recognition you can’t do that with just those crops.”

A box of seeds labelled ‘Irish Seeds for Svalbard Global Seed Vault’.

Photographer: Ivar Kvaal for Bloomberg Businessweek

Good intentions weren’t enough for everyone there.

Patrick Mulvany, an agriculturalist and adviser on biodiversity and food sovereignty said the real efforts aren’t being made where they are needed the most: on the ground with the farmers who are not getting adequately compensated.

“Unless that happens our future food is very insecure,” he said. “You can have as many seeds as you want locked up in the vault here but they deteriorate a little bit over time and they aren’t adapting to climate and new social pressures.”

In a ceremony coinciding with the 10th anniversary, gene banks around the world deposit new seeds. They included rice, maize, African eggplant and lentils. It just received the millionth seed, though it says it needs another 2 million.

Some had other goals than food in mind. The Irish placed barley seeds to ensure the continuity of Irish whiskey—which will be in certain demand should the worst come to pass.