First you need the right set of arguments.

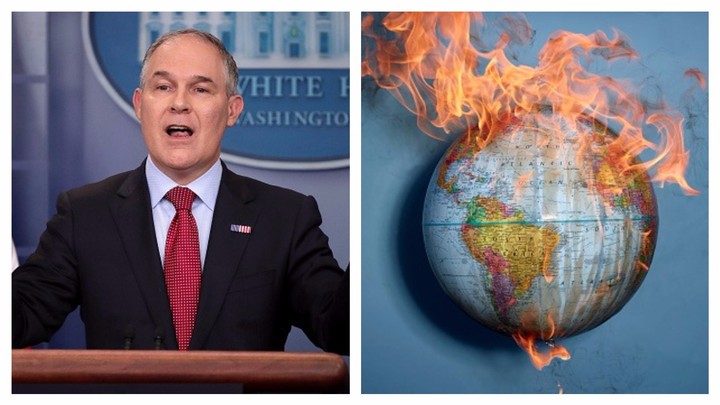

Chip Somodevilla/Matthew Salacuse/Getty Images

Recently, Scott Pruitt, the current head of the Environmental Protection Agency, called climate science into question—again. His newest debunking initiative involves gathering researchers to debate whether climate change is human-caused, essentially brushing off the fact it’s well-established by the scientific community that it is. While discussion is typically welcome in science, experts fear that Pruitt (who is already a climate change skeptic) will prioritize cynical voices.

Chances are you have a version of Scott Pruitt in your life. Maybe it’s a co-worker at the office who thinks climate change is a hoax or a relative who says global warming is normal and natural because “the climate has changed before.” Chances are you have engaged in a debate of your own about climate change and if you’re a believer, maybe you’ve tried to win them over, adding that some pretty credible nonpartisan organizations have found that climate change is happening and that we humans are to blame. But your Pruitt isn’t budging. Is it possible to change their mind?

It is indeed, but we’re going to be honest: Embarking on this epic quest will not be easy. It’s going to require time, patience, and listening (basically all the skills that nobody has time for these days). But with that and a few communication adjustments and talking points, it can be done. We asked climate science communication experts (and one researcher who studies evolution, because hey, that’s another heated topic) about how to approach the dissenters.

Appeal to the other person’s values.

When we talk about why we should tackle climate change, common reasons include protecting nature from harm or being compassionate toward communities that might suffer as a result. Someone might show you a picture of a polar bear family on a lone piece of ice or discuss how those in poverty will see their situations worsen if we keep messing with the environment.

But experts say these messages fall short. “There’s an idea called moral foundations theory that hypothesizes that liberals and conservatives prioritize different values,” says Asheley Landrum, assistant professor of science communication at Texas Tech University. “Research has found that liberals tend to place a higher value on compassion and fairness, while conservatives favor purity, obeying authority, and loyalty, so you can’t keep targeting conservatives with liberal tropes—talking about caring or compassion with them will likely be ineffective.”

If you’re trying to convince someone who leans left, you can stick with the polar bear and keeping tugging at their heart strings with talk of how unfair it will be to our children if the world is poisoned, but if you’re with a conservative, it’s wise to change up your approach—science has found that personalized climate-related messages work better. A study published in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology reported that when conservative participants were presented with messages about how a pro-environmental agenda maintains the purity of America or how taking responsibility for yourself and the land you call home is patriotic, they were more likely to support that agenda. Another study found that framing a recycling effort as an obligation to adhere to authority and be part of a group—by showing a state’s increase in recycling participation over the year—actually increased recycling efforts in conservative households.

Start with trust, not facts.

You know how it seems intuitive to want to give everyone all the data and statistics and studies that support climate change right away? Well, you should avoid that when you’re starting a conversation. “People don’t like to be the target of a persuasive effort, so they are likely to shut down if you start throwing out evidence,” says Liz Barnes, a PhD student who focuses on evolution education research at Arizona State University. One 2010 study found that correcting people could lead them to further double down on their own misperceptions, something researchers called the “backfire effect.”

More From Tonic: Death in a Can

Barnes says that people are more receptive to evidence when there’s a sense of trust between people. In the case of climate change or really any controversial topic, you won’t build trust if you tell (or imply!) that someone’s views are wrong, uneducated, or that there’s a “right way to think about this.”

Instead, ask questions about their views and how they came to be. What influences their current ideas about climate science? What makes them uncertain that climate change is happening?

As an instructor who teaches evolution, often to students who don’t believe in it, Barnes stresses the importance of being respectful and keeping an open mind. “My implicit goal is to help students accept evolution, but I do not say ‘you have to accept it to get an A.’ I first acknowledge that students may have differing opinions about evolution, let them know I will respect their views regardless of what they are, and tell them I hope they would feel comfortable expressing any concerns about the material. You will be more successful at fostering acceptance of evolution if students feel as if they have the freedom to make that decision themselves.”

And be realistic: “Maybe you won’t change their mind that particular time but you might come off in a different, more approachable way than other people who have tried to sway them,” she adds. “People are so used to coming into these conversations with a battle mindset, when you show that you’re not there to prove them wrong, they’ll be more open to you the next time. You can plant a seed and grow it.”

Let the skeptics know that there is a consensus among scientists.

In a 2016 article in the National Review, Pruitt wrote that “scientists continue to disagree about the degree and extent of global warming and its connection to the actions of mankind.” It’s the classic comeback: Why should we believe in climate change, if even the experts can’t agree on it?

But there’s actually no disagreement, says Edward Maibach, director of the Center for Climate Change Communication at George Mason University. “Despite what frequently floats around in the media, around 97 percent of climate scientists believe that climate change is happening, that it is human-caused, and is worrisome.”

Helping people understand that experts are on the same page about melting ice caps and climbing temperatures could actually sway them—in fact, researchers refer to this perceived acceptance as the “gateway” to getting people on board with climate change. In a 2015 study published in PLOS One, Maibach and colleagues found that telling people that experts agreed on climate change increased the chances that those individuals would accept that climate change was happening, was human-caused, and presented a real threat. Extra encouraging: That strategy was also particularly influential on Republicans, though liberals might also need a nudge. According to a recent Pew Research poll, only 55 percent of liberal Democrats believe that nearly all experts agree that humans are responsible for climate change.

These results are important to consider, since other studies have found that when the public gets a whiff of even a small amount of disagreement among experts, they’re less likely to support environmental policies.

Focus on what’s already happened and keep it local.

There are two things humans aren’t really particularly good at: thinking about the future and caring about what’s happening outside of their bubble. (Do we have to remind of what went down in November 2016?)

How does this relate to climate change? Well, often both researchers and lay people attempt to school other individuals about climate science using projections about what’s going to happen in the coming years. Things like “By 2040, sea levels will rise X amount” or “In 15 years, we won’t be able to farm X crops because it will be so hot.” While data like that can have some shock value, people might not take it seriously. “When we look at projections going forward it’s pretty easy to discount that data, not because they are wrong, but it’s just that we all know our local meteorologists doesn’t get the three-day forecast right, so we tend to be leery of a three decade or ten-decade prediction,” says Maibach. Similarly, throwing out statistics about what is happening in Bangladesh or even in another part of the country is likely to be ineffective, unless someone happens to have personal interests in said place.

Instead, Maibach suggests offering data from the past, focusing on changes that have already happened, “which gives people less incentive to distrust them, since it’s a historical fact.”

Next, keep it local, because things tend to stick better when people have learned from experience, something called experiential learning. In a 2012 study published in Nature Climate Change, Maibach found that people who are less engaged with the issue of climate change (which is a whopping 75% of Americans) are more likely to be influenced by experiential learning. So gently and respectfully talk to them about what’s changed in their community. Chat about the increased coastal flooding or data about the stronger heat waves that have occurred in the last 10 years. Have they noticed that the first frost comes later or that summers are longer? As people experience global warming, they are more likely to acknowledge it is happening.

Dish out neutral sources.

Thanks to confirmation bias, we (both liberals, conservatives, and everyone in between) tend to seek out sources that support our already established views. But that can be a dangerous path, especially as it relates to climate science. In a study published in the Public Understanding of Science, Maibach and his colleagues summarized data that found that conservative media outlets feature more stories that question whether humans are responsible for climate change, claim that there is a lack of consensus among scientists, and consistently present climate change-denying experts as more “objective.” Ultimately, these story facets reduce viewers’ trust in scientists and their certainty that climate change is happening.

At the same time, suggesting your friend or uncle flip on CNN or forwarding them links to left-leaning sites for some media consumption diversity might be a challenge (especially for those motivated reasoners!), so point them to more neutral sources. Maibach suggests the National Climate Change Assessment, National Academy of Sciences, and American Association for the Advancement of Sciences websites, which all have very digestible reports written in simple English.

Give them examples of climate change-accepting role models

Some people are so wrapped up in their political identity that they may have a fear that if they accept climate change, they are no longer a Republican, Landrum says. “So, you want to show them that supporting climate change doesn’t conflict with Republican values.”

Assuming that your skeptic leans right, what works? Try citing conservative leaders who support climate change. Jerry Taylor is a great example of a conservative who switched sides. Bob Inglis, Lynn Scarlett, and Hank Paulson are also on board. Ask your skeptic what they think of their initiatives or their stance as conservatives—again, focus on learning through questions, rather than rattling off these individuals’ achievements or resumes from the get-go.

Recently Barnes published a study about how to reconcile religion and evolution in the classroom. She says that bringing in a biologist who was a practicing Roman Catholic and public defender of evolution helped students understand that religion and evolution don’t need to clash. “The biggest misconception, even in scientists, is that religion and evolution are mutually exclusive, but that’s not the case. With a religious, evolution-supporting role model, we hoped to show students that they could be compatible,” she adds. And it worked: along with discussions about religion and evolution, they were able to reduce students’ perceived conflict between the two by 50 percent.

Read This Next: A Totally Heat-Ravaged Planet is Just 83 Years Away