His duplicity bears a disturbing resemblance to Putin-style propaganda.

At a speech in Harrisburg, Pa., on April 29Carolyn Kaster/AP

“26 hours, 29 Trumpian False or Misleading Claims.”

That was the headline on a piece last week from the Washington Post, whose reporters continued the herculean task of debunking wave after wave of President Donald Trump’s lies. (It turned out there was a 30th Trump falsehood in that time frame, regarding the head of the Boy Scouts.) The New York Times keeps a running tally of the president’s lies since Inauguration Day, and PolitiFact has scrutinized and rated 69 percent of Trump’s statements as mostly false, false, or “pants on fire.”

Trump’s chronic duplicity may be pathological, as some experts have suggested. But what else might be going on here? In fact, the 45th president’s stream of lies echoes a contemporary form of Russian propaganda known as the “Firehose of Falsehood.”

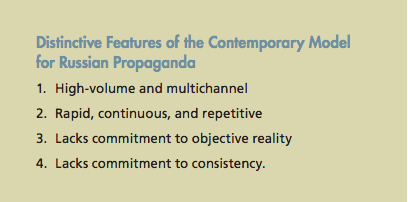

In 2016, the nonpartisan research organization RAND released a study of messaging techniques seen in Kremlin-controlled media. The researchers described two key features: “high numbers of channels and messages” and “a shameless willingness to disseminate partial truths or outright fictions.”

The result of those tactics? “New Russian propaganda entertains, confuses and overwhelms the audience.”

Indeed, Trump’s style as a mendacious media phenomenon resonates strongly with RAND’s findings from the study, which also explains the efficacy of the Russian propaganda tactics. Here are the key examples:

RAND: “Russian propaganda is produced in incredibly large volumes and is broadcast or otherwise distributed via a large number of channels.”

Trump is known for his high-volume use of Twitter, tweeting about 500 times in his first 100 days in office, using both his personal account and the official @POTUS account. His tweets often become the subject of news stories and sometimes provoke entire news cycles’ worth of coverage across the mainstream media, such as when he accused former President Barack Obama of “wiretapping” his campaign and suggested he might have secret recordings of ex-FBI Director James Comey. Both CNN and the Los Angeles Times keep running tweet trackers on the president. Trump has also appeared on White House-friendly cable news shows like Fox & Friends—a show he also tweets about effusively on a regular basis.

Trump is also a prolific liar on stage: Of the 29 false statements the Washington Post tracked last week, five came in a speech to Boy Scouts, two came from a news conference, and a whopping 15 came from a rally in Youngstown, Ohio. (Seven others came from, where else, his personal Twitter feed.)

The deluge matters, notes RAND: “The experimental psychology literature suggests that, all other things being equal, messages received in greater volume and from more sources will be more persuasive.”

RAND: “Russian propaganda is rapid, continuous, and repetitive”

Trump often repeats misleading statements in rapid, successive tweets. As the Post captured, in three tweets within 13 minutes on the evening of July 24, he railed against the “Amazon Washington Post,” and in three tweets between 3:03 a.m. and 3:21 a.m. on July 25, he railed against his old foe Hillary Clinton, calling Attorney General Jeff Sessions “VERY weak” for not investigating her, and wrongly saying that acting FBI Director Andrew McCabe’s wife received money from Clinton.

Why the technique works: RAND explains that “repetition leads to familiarity, and familiarity leads to acceptance.”

RAND: “Russian propaganda makes no commitment to objective reality”

Phony news stories are a staple of Vladimir Putin’s Russia—and as Mother Jones has detailed, Trump and his team have been caught repeating several that originated in Russian news outlets.

Trump also has a habit of repeating false statements that can be very easily checked—such as lies about the number of bills he has signed. On July 17: “We’ve signed more bills—and I’m talking about through the Legislature—than any president, ever.” And then on July 21: “I heard that Harry Truman was first, and then we beat him. These are approved by Congress. These are not just executive orders.” The historical record shows that many presidents—including Dwight Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy, Jimmy Carter, Richard Nixon, George H.W. Bush, and Bill Clinton—all signed more bills within their first six months of office.

From RAND’s 2016 study

RAND notes that this propaganda strategy flies in the face of conventional wisdom that “the truth always wins.” However, the researchers found, “Even when people are aware that some sources (such as political campaign rhetoric) have the potential to contain misinformation, they still show a poor ability to discriminate between information that is false and information that is correct.” Confirmation bias and emotion also factor in: “Stories or accounts that create emotional arousal in the recipient (e.g., disgust, fear, happiness) are much more likely to be passed on, whether they are true or not.”

RAND: “Russian propaganda is not committed to consistency”

Trump’s story often changes, even among his own false statements. The New York Times tracked five times this spring that the president changed his story about when China had stopped manipulating its currency—from “the time I took office” to “since I started running” to “since I’ve been talking about currency manipulation.” The reality is, China stopped manipulating its currency years ago.

According to RAND, this approach exploits relatively low expectations of truth among the public regarding statements from politicians. In Russia, “Putin’s fabrications, though more egregious than the routine, might be perceived as just more of what is expected from politicians in general and might not constrain his future influence potential.” In the United States, Trump may be taking advantage of historically low public trust in both the media and politicians.

RAND: “Don’t expect to counter the firehose of falsehood with the squirt gun of truth.”

The Washington Post has called Trump “the most fact-checked politician.” Yet, the RAND research found that pointing out specific falsehoods was an ineffective tool against the propaganda techniques they studied in Russia because “people will have trouble recalling which information they have received is the disinformation and which is the truth.” The researchers acknowledged the challenges that other governments and organizations like NATO have in countering Russian propaganda, and advised against taking on the propaganda messages directly.

Some responses proposed by the researchers may also hold clues for media struggling to contend with Trump’s unprecedented behavior in the Oval Office. The researchers suggest making the first impression on an issue by priming audiences with accurate information, to get in front of a potentially misleading message. And they advise exposing the method: “Highlight the ways propagandists attempt to manipulate audiences,” they say, “rather than fighting the specific manipulations.”

For the American media, it may well be a matter of doing both, and often.