Calling the police on a homeless person can be damaging or even deadly, a new app aims to quickly get them less confrontational assistance.

Walking down a street in San Francisco’s Tenderloin neighborhood–like many other parts of the city–it’s not uncommon to see a homeless person in the throes of a mental health crisis. People passing by often call 911. But an app called Concrn offers an alternative: if you report someone in distress, a trained community member will come offer help instead of the police.

advertisement

Advertisement

Scroll to continue with content

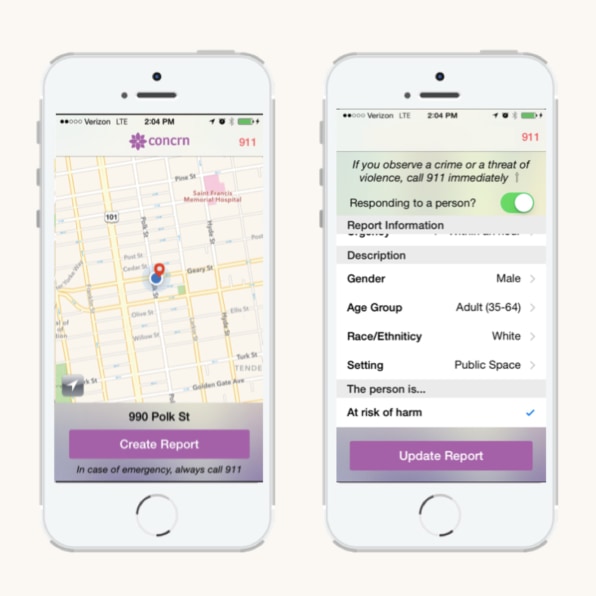

Neil Shah, one of the co-founders of Concrn, which is part of the 2017 class of the tech nonprofit accelerator Fast Forward, describes it as “a community-based crisis reporting app.” “You can submit a crisis report, and our back-end, cloud-based web dispatch platform then rapidly deploys community members that we have trained in compassionate response to de-escalate the crisis, and triage people to crucial services and follow-up care.”

Concrn’s staff includes a core group of seven trained, paid, part-time responders who are community members in the Tenderloin, so the organization can also provide jobs in a low-income neighborhood. It also works with volunteers from a variety of backgrounds; some are social workers, some come from the tech world. To become a responder, each person spends 20 hours studying compassionate response techniques such as empathic listening, using a program adapted from Stanford University’s Center for Compassion and Altruism Research. They then spend 80 hours on the street with mentorship from a lead responder.

The nonprofit was created after one of the co-founders, Jacob Savage, was in training as a police officer in Palo Alto. “He realized that responding to mental health crises from a punitive standpoint, from the police, often did not lead to good outcomes,” says Shah.

Calling the police on a homeless person in distress can often cause more harm than good, ending up with the person needing help in jail instead of in treatment. In the worst-case scenarios, homeless people in various cities have been killed by police. In 2014, Albuquerque police who responded to a complaint about a homeless man camping behind a house ended up shooting the man, who had schizophrenia. In 2016, Sacramento police officers who responded to calls about a mentally ill, homeless man with a knife attempted to run him over with their squad car and then shot him. In San Francisco in 2016, a mentally ill homeless man with a knife was also shot and killed by police.

In San Francisco, the city has stepped up efforts for police officers to try to guide homeless people to local services rather than issuing tickets or arresting them. But police and EMTs have to deal with a huge volume of calls as San Francisco struggles with a large homeless population; the city gets between 4,000 and 5,000 calls every month. Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital, which performs psychiatric evaluative services, often has to quickly discharge patients back onto the street.

Another city team of staff who respond to psychiatric crises on the street also has limited staff. “One option in the city is Mobile Crisis, a trained team of health workers that will respond, but it’s extremely limited,” says Kelley Cutler, a human rights organizer for the local nonprofit Coalition on Homelessness. “So we need more of those. Part of the concept of Concrn is tapping into that.”

Concrn can also help in a more informal way than city staff. “I think it helps fill some gaps between what we can do officially as a system, and what can happen a little bit more on the friend level,” says Sam Dodge, deputy director of the San Francisco Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing. “There’s less of a specific agenda that they have to complete. And our workers are often triaging between 4,000 people on the street every day… there’s a lot of people that could use some direction, some friendship, a little bit of sophistication on how to navigate to some services or not.”

When Concrn responds to someone on the street, they focus on listening to their needs, and help calm them and provide referrals to services. In one recent case, they received a mobile app report about a husband and wife in need of mental health support, and after developing the couple’s trust, helped them find a shelter bed. Two months later, after staying in touch with them, Concrn staff learned that the couple had an opportunity for supportive housing, but couldn’t be found.

“If they weren’t found that day, they were going to lose their housing reservation,” says Shah. “So we were able to quickly coordinate amongst our responders through the backend dispatch system and find this couple, and then coordinate with a nurse to make sure that they got the right psychiatric medication, and coordinate with the homeless outreach team to get them over to the housing.”

Right now, Concrn’s system is partly manual–after receiving a report, someone at Concrn typically calls back the reporter for more information and then manually dispatches a responder via text message; responders can text back “yes” or “no” depending on their availability. But the group is developing a version of the app that will automatically match reporters and responders, and that will allow them to chat directly if needed. Responders will be able to mark themselves on call and receive push notifications.

The nonprofit is also considering digitizing its compassionate care training so that it can easily be adopted by organizations and agencies in other parts of the country.

Like other outreach programs, it’s limited by the available services that it can refer people to. “The reality as an outreach worker is that there are so few resources available,” says Cutler. “Here in San Francisco, we have over 1,000 people on the single adult shelter wait list. That doesn’t even include children and families. That number right there is pretty stunning and a prime example of the crisis that we’re in. We’re in a housing crisis. We need housing and real solutions.” She says that while the app seems positive, she’s skeptical it will be able to help much when there are so few services and options for the homeless to be referred to.

For anyone responding to a homeless person in distress, it also isn’t always possible to immediately help them. Concrn sometimes makes the analogy of like being a Lyft for sending help, but Dodge makes the point that when the city gets a call about a homeless person, callers often expect instant solutions that aren’t possible because of the complexities of legal rights and administrative processes.

“You’ll sometimes have officers in the middle of the night having to navigate multiple complex systems or social workers working with someone who’s very traumatized and depressed,” Dodge says. “We’ve trained ourselves, not unlike with Uber or Amazon Prime or something, that you press this button and it happens, and if not, then let’s have accountability. But humans are just more difficult than that.”

The city, like others, also needs a better solution for the part of the homeless population struggling with mental illness. But while it doesn’t address the deeper systemic problems, Concrn could help provide a little relief–and give concerned San Franciscans something productive to do when calling 911 (or 311, the city’s customer service center) isn’t the right option.

“Traditional approaches, in particular, our jails and prisons, are almost singularly unsuited to addressing mental health, or in the case of hospitals, simply don’t have the capacity for this task, and relying on them for a purpose which they’re never intended for has proven highly counterproductive,” says Shah. “So where we see Concrn stepping in is being able to be the linkage between the behavioral health system and the criminal justice system in a way that utilizes technology . . . to better reduce the burden on emergency services, and to get people connected to care.”