Elsewhere, gains are slow and low-income households are paying more rent than ever.

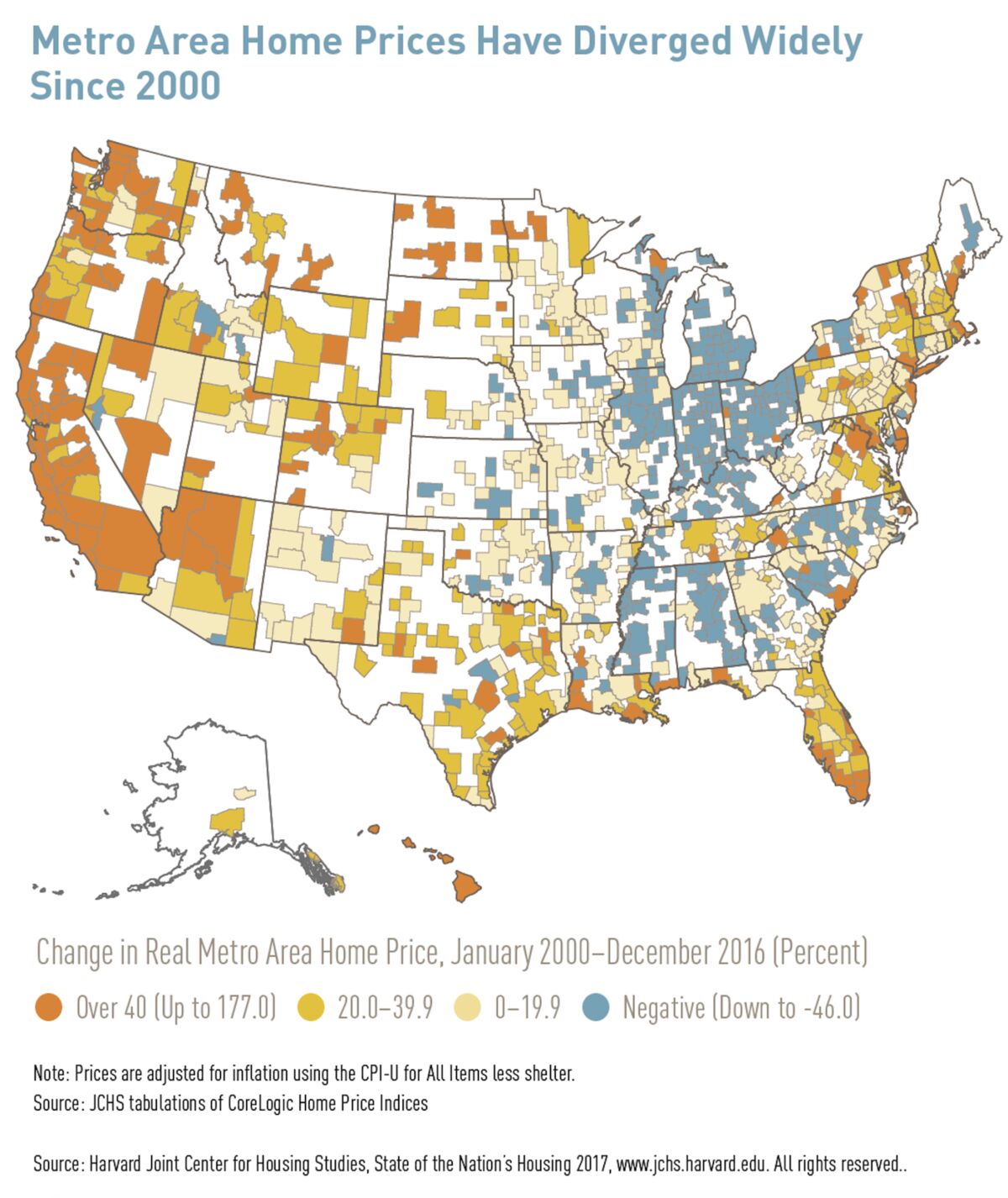

For further evidence of the uneven recovery among U.S. housing markets, how’s this: In the 10 most expensive U.S. metropolitan areas, median home values have increased by 63 percent since 2000, after adjusting for inflation. In the 10 cheapest metros, median values rose by just 3.6 percent.

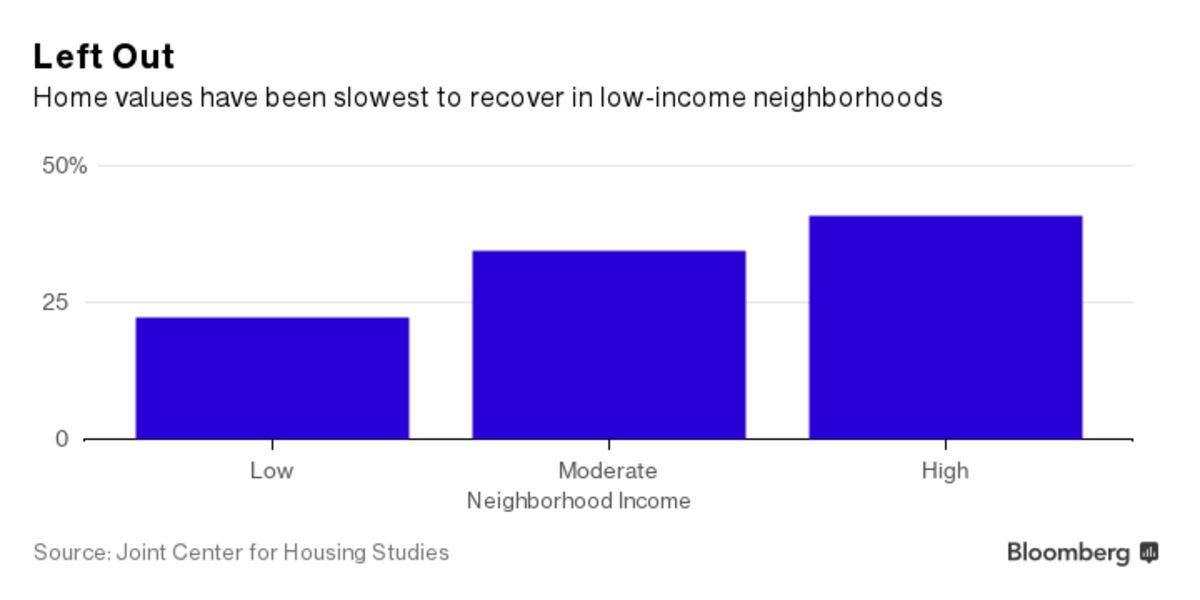

That finding, and the others illustrated by the charts below, comes from the State of the Nation’s Housing, an annual report published Friday by Harvard University’s Joint Center For Housing Studies. While home prices have increased sharply in expensive coastal cities, plenty of urban centers are lagging behind. Home prices in 3 out of 5 metropolitan areas remain below their pre-recession peak, and home prices in low-income neighborhoods are faring even worse.

Meanwhile, the number of Americans spending 50 percent of their income on rent is near historic highs, something likely to get even worse if proposed budget cuts to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development eliminate rental assistance for hundreds of thousands. Demand for rental units continues to rise, pushing rents higher.

The good news—such as it is—is that slow price appreciation in much of the country outside the hot metros means for-sale units there remain relatively affordable for more families.

Home prices increased in 97 out of the 100 largest metropolitan areas, according to the report. Nationally, nominal prices returned to the peaks they held before the Great Recession. But when you adjust for inflation, those prices are as much as 16 percent below past peaks. And appreciation hasn’t been evenly distributed: A May report from Trulia showed that nationally, just 1 in 3 homes has recovered peak value. The Harvard report, however, shows the price gains have been concentrated in high-income neighborhoods.

The flip side of low appreciation should be greater affordability for home buyers. Indeed, 59 percent of households in U.S. metros can afford to purchase the median home, the Harvard report stated, and in 1 in 5 metros, 75 percent can afford to buy. (In this case, the report defines affordability based on a 5 percent down-payment and monthly mortgage payments of no more than 36 percent of household income.)

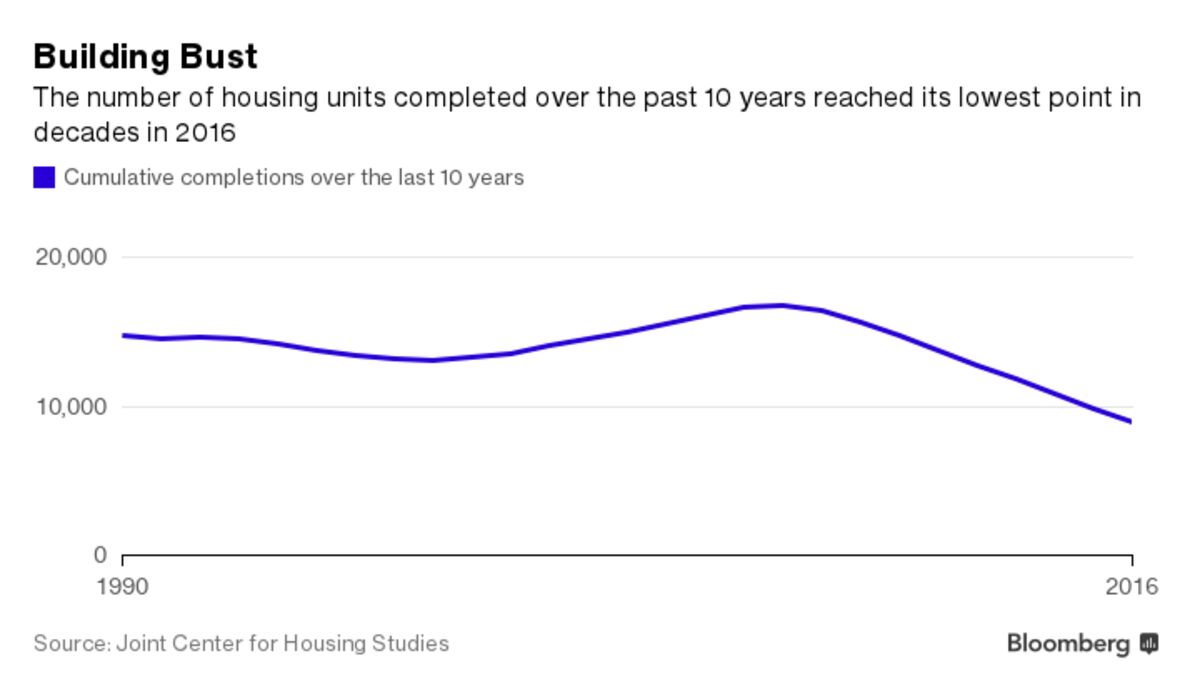

But many local markets suffer from low inventory, the report notes, partly because of the sluggish pace of new construction: The U.S. added fewer housing units over the decade ending in 2016 than in any 10-year period since 1990.

Joint Center for Housing Studies

And while a significant number of Americans spend half of their income on rent, that figure did tick down a bit in 2015, to 11.1 million. That’s still 49 percent more severely rent-burdened households compared with 2001. The vast majority of those households earn less than $30,000 a year.

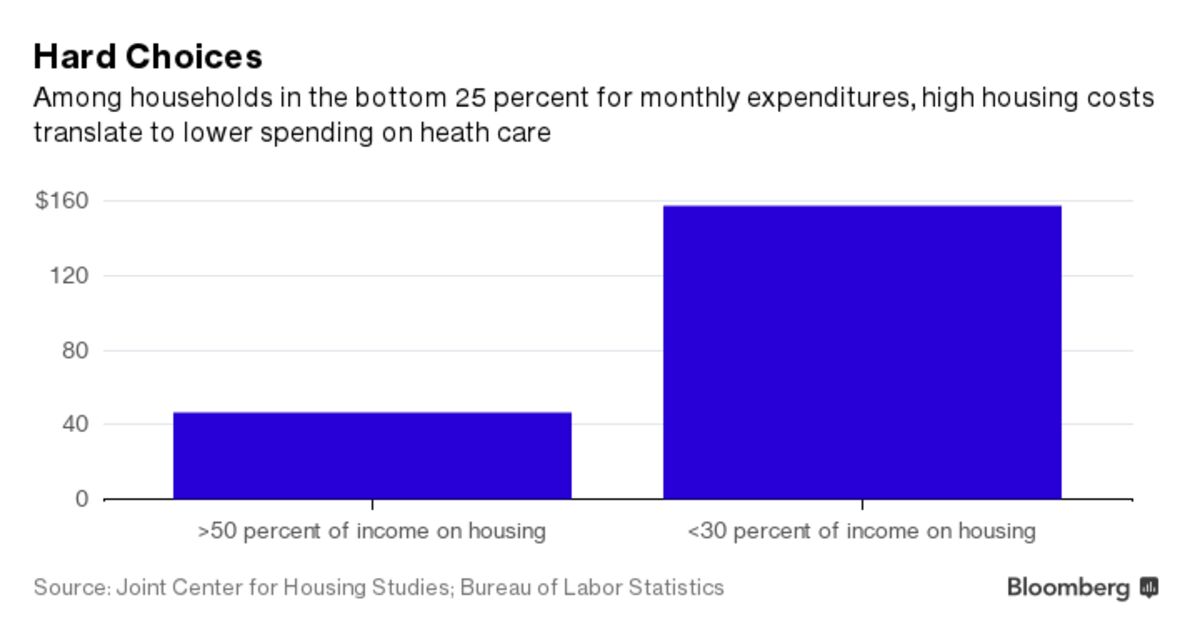

Regardless of income, or whether they own or rent their homes, families that spend half their income on housing are forced to make sacrifices elsewhere in their budgets. When the poorest families pay less for housing, the extra money goes to necessities like health care. Among households that fall in the bottom 25 percent for total consumer spending, those that spent less than 30 percent of their income on housing spent three times as much on health care.

Those hoping for relief in the form of new rental stock may be waiting for a while. After growing by leaps following the foreclosure crisis, the nation’s stock of single-family rentals actually fell in 2015, the last year for which the report offers data. Low-rent units, meanwhile, are being replaced by more expensive offerings, the report said. That is where the money is.