A vote for tax cuts today is tantamount to a vote for tax hikes tomorrow.

There’s a reason Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin keeps insisting that his boss’s tax-cut plan will fully pay for itself through faster economic growth. Budgetary politics make it hard for him to say anything else. Senate rules require 60 votes for any tax cut that would raise deficits beyond a window of 10 years from the date of passage. Conceding upfront that President Donald Trump’s plan would generate more red ink in the medium to long term would be accepting defeat before the legislative fight has even begun.

“This will pay for itself with growth and with reduction of different deductions and closing loopholes,” Mnuchin said at an April 26 briefing on the one-page outline of a tax plan. National Economic Council Director Gary Cohn didn’t go that far, though he did call the plan “a once-in-a-generation opportunity to do something really big.”

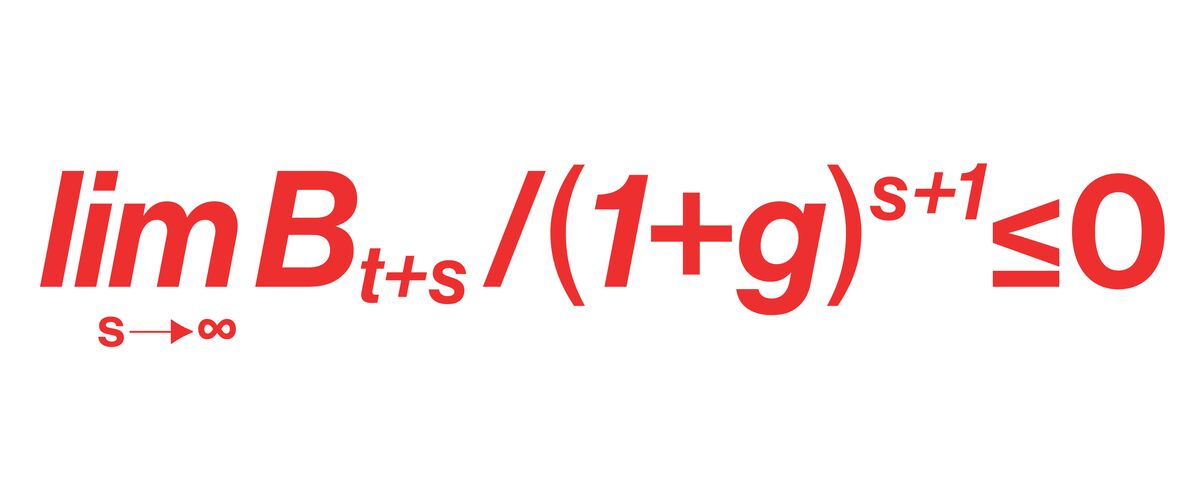

This equation is the transversality condition for a government budget. Debt is B, the present time is t, the economy’s growth rate is g, the future time period is s, and infinity is ∞. What all this means is that the present value of government spending has to be matched by the present value of all receipts … in other words, Trump’s tax plan is unsustainable.

Math is not on their side. The budgetary impact of tax legislation is scored by the nonpartisan staff of Congress’s Joint Committee on Taxation. Judging from its past calculations, the JCT is likely to agree with independent budget wonks, on the left and right, who have concluded that Trump’s plan would create a gusher of red ink. “No individual tax cut pays for itself,” says Alan Cole, an economist at the right-of-center Tax Foundation. “There has to be a strong mix of tax cuts and revenue-raisers—a good mix of both candies and vegetables. Right now I see things as a little short on vegetables.”

The Trump tax plan, because it generates deficits as far as the eye can see, violates what’s known as the transversality condition, which says that debt relative to the size of the economy cannot grow to infinity; fiscal policy is sustainable over the long run only if there will be surpluses in the future to offset deficits today. True, Keynesian-style tax cuts like President Barack Obama’s 2009 stimulus package also generate red ink, but they’re designed to phase out when the economy no longer needs the jolt.

What makes the Trump tax cuts violate the transversality condition is that they’re intended to be permanent. “If you propose a big tax cut without offsetting spending cuts, then it’s essentially an incomplete proposal,” says Eric Toder, co-director of the Tax Policy Center, a venture of the Urban Institute and Brookings Institution. “What you’re implicitly proposing is lower spending and higher taxes in the future.”

The federal budget was on the wrong track even before Trump took office. The Congressional Budget Office said on March 30 that, assuming current laws remain generally unchanged, federal debt held by the public would grow from 77 percent of gross domestic product now to 146 percent in 2046, with no end to the upward trend on the horizon. That’s unsustainable. “We have this enormous fiscal gap. We have to be cutting it, not raising it,” says Laurence Kotlikoff, a Boston University economist who harped on deficits when he ran for president last year as an independent.

Since Trump can’t credibly claim that his tax cuts will pay for themselves and not increase the deficit, he’s left with unpleasant options. One is to curtail his cuts in hopes of achieving a score of revenue neutrality from the JCT. He’s already dropped hints that he considers the one-pager as a starting point for negotiations, not a final demand. But while taking candy out of the tax package and adding vegetables would please the JCT, it would make it harder to pass the bill by creating some clear losers: If revenue is to be neutral, inevitably there will be groups whose taxes go up—such as New Yorkers and Californians who would lose the ability to deduct state and local income taxes.

A second option is to schedule the tax cuts to expire by the end of the JCT’s 10-year scoring period, so they can pass with a simple majority in the Senate. That’s what President George W. Bush did, although some of his cuts were later extended. But businesses don’t like to make investment decisions based on tax cuts that won’t last.

A tempting alternative is for Congress to change its rules. Senator Pat Toomey, a Pennsylvania Republican, issued a press release on April 26 disdaining “arbitrary budget constraints” and suggesting that it might not be necessary to make Trump’s tax plan revenue-neutral at the end of 10 years. “There are ways to navigate these obstacles,” the statement said, “including the use of a longer horizon,” meaning more time for cuts to generate growth and become revenue-neutral. The Wall Street Journal reported on May 2 that a senior administration official said in late April that no rule requires the window for scoring tax proposals to be 10 years long. A scoring window of 20 or 30 years wouldn’t magically make a deficit-generating tax cut into a surplus-generating one, but it would please businesses by giving them low tax rates for longer.

A third option is to press hard on the argument that any revenue losses are temporary and will be made up as the tax cuts boost economic growth. This is Mnuchin’s case. Likewise, Vice President Mike Pence said on Meet the Press on April 30 that deficits could grow “maybe in the short term,” but added, “If we don’t get this economy growing at 3 percent or more, as the president believes that we can, we’re never going to meet the obligations that we’ve made today.”

Pence is right that stronger growth would solve a host of problems. This is where things get interesting. Suppose that Trump’s tax cuts raise economic growth over the long term, just not enough to fully pay for themselves. Deficits would rise. But if—hypothetically—debt grew more slowly than the economy, debt would shrink in relation to GDP, making it easier to bear. The tax cuts, despite not being revenue-neutral, would bring the budget closer to satisfying the transversality condition—i.e., being sustainable.

Mnuchin hinted at one point in the April 26 briefing that debt sustainability, not revenue neutrality, was the right standard by which to judge Trump’s tax cuts. He said that “this plan is going to lower the debt-to-GDP” ratio. Expect to hear more of that kind of talk in future GOP messaging.

The bottom line: Trump’s plan to cut taxes might lead to higher GDP growth, but without spending cuts it will certainly increase the deficit.