Coppa’s crowning glory was its wildly creative murals, done on the fly by the artists and writers who made the place their second home. The Coppa murals may have been the hippest, wittiest, most ahead-of-their-time artistic improvisations ever to froth up in San Francisco. They were a hilariously proto-Dadaist masterpiece, created 10 years before that anarchic artistic movement, whose 100th anniversary is being celebrated this month by City Lights books, was born at the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich.

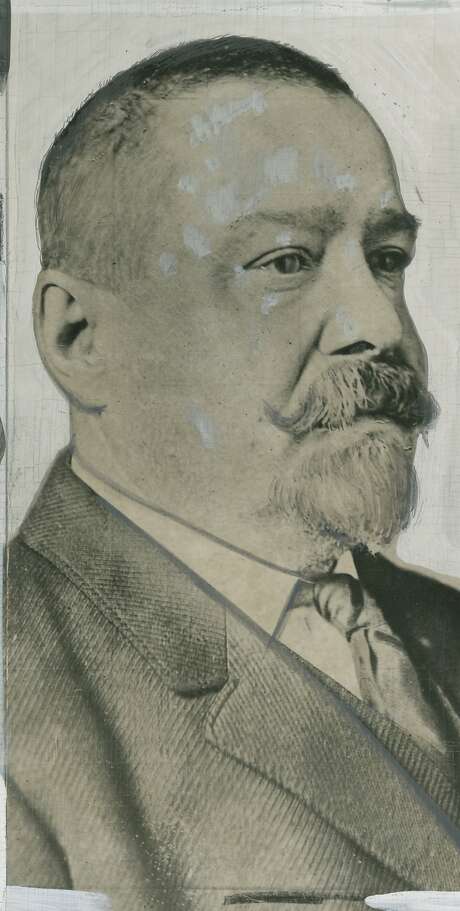

Original Coppa’s Restaurant, to give its full name, was opened in 1904 by Giuseppe Coppa, an Italian from Turin who had come to California in the 1890s. It was on the ground floor of the Montgomery Block, also known as the Monkey Block, the huge 1853 building located where the Transamerica Pyramid now stands.

As Warren Unna notes in “The Coppa Murals: A Pageant of Bohemian Life in San Francisco at the Turn of the Century,” Coppa’s first regular patrons were Italian fishermen wearing scarlet Garibaldis. Soon, however, a convivial group of free-spirited writers and artists discovered the long, narrow room with 21 tables.

Poppa Coppa, as he was affectionately called, routinely extended credit to his often-impecunious scribblers and daubers. Not that prices were steep: The table d’hotel meal, which included salad, excellent pasta, plenty of crusty French bread, an entrée, black coffee and good red wine, cost 50 cents.

The leader of the Coppa gang was Porter Garnett, a writer, editor and designer best known as the co-creator, with fellow Coppan Gelett Burgess, of the whimsical 1895 literary magazine the Lark. The most flamboyant regular was Mexican-born painter Xavier Martinez, who had studied in Paris, had a drooping mustache and was given to belting out French chansons at the drop of his soft-brimmed hat. His friend Maynard Dixon, a noted painter and illustrator who smoked marijuana on a trip to Mexico with Martinez and called his Coppa pals “the fuzzy bunch,” was another key member.

George Sterling, a hard-drinking, moody bohemian poet whom Burgess described as an “eager girlhound,” often held forth at Coppa’s. The short-story writer James Hopper, who was to write the finest piece of journalism about the 1906 earthquake and fire, rubbed shoulders with the earnest young socialist Jack London, who would write the second-best piece.

This merry gang gathered at the center table at Coppa’s to talk about the universe, art and their love lives, which they routinely tried to improve by bringing in women on a kind of tryout basis. “There was an unwritten rule that only one new girlfriend at a time could be brought to the center table,” Unna writes. “Then the group would take a vote under the table. Mary Austin rated a thumbs down when George Sterling brought her and she wasn’t asked again.

“‘She was writing beautiful stuff but she wasn’t pretty,’” Jimmy Hopper, the Carmel writer, once remarked, and then explained, ‘The pretty ones didn’t have to write very much to get in again.’”

Time has repaid the group for its treatment of Austin: Her works are still read today, while those of the Coppa gang, except for London’s, are largely (if not always justly) forgotten.

The Coppa murals were inspired when Garnett and sculptor Robert Aitken spontaneously drew a caricature of former Mayor James Phelan on a blank screen at the Bohemian Club. Encouraged by the result, they offered to redo Coppa’s red-wallpaper decor. Coppa agreed and turned the place over to them on a Sunday in 1905, giving them free lunch and all the wine they could drink.

That day Garnett took a box of chalk and climbed on a table, with no idea what he was going to draw.

“The first thing was a lobster,” Unna writes, “the fons et origo of the Coppa Gallery.” A gigantic drawing of a nearly nude man and woman by Aitken followed.

Over the coming weekends, other Coppans added their bits, all in charcoal, chalk or crayon. Soon the cafe’s upper walls were covered with a melange of surreal sketches, archaic quotations, mock Homeric lists of great artists that included many of the Coppans, and the weird doodley creatures that Burgess called “Goops,” all topped with a frieze of stenciled black cats.

Garnett told Unna that the murals’ only objective was “that most engaging of all games — fooling the public.” One scroll, by Carolyn Wells, the first woman contributor to the Lark, contained the words, “Oh, love, dead and your adjectives still in you!” Another scroll, taken from a Constantinople street cry, read, “In the name of the prophet, figs!”

Next to a large devil catching a fish above the words, “It is a crime,” Garnett drew a matron peering through her lorgnette at a table of bohemians, saying “Freaks!” to her bald companion, who responds, “Yes, artists!” One of the artists returns the compliment, saying, “Rastaquoueres!” a southern French word for Philistines, to which a companion replies, “Oui, cretins!”

In an interview with Unna the day before he died in 1951, Garnett took pains to make clear that the Coppans were not “tainted with that vulgar exhibitionism known as professional bohemianism. … They had no knowledge of being on display, nor were they bent on outraging or titillating a peering public. … The Coppans lived for the joy of living.”

Ironically, the murals soon attracted precisely those “rastaquoueres” the Coppans detested, who came in droves to gawk.

One of the cryptic quotations on the wall, from Oscar Wilde’s “Salome,” read, “Something terrible is about to happen.” On April 18, 1906, it did. The earthquake spared the Monkey Block, but looters broke into the cafe and destroyed everything.

At the request of the Coppans, Coppa opened the ruined restaurant and served a last supper by candlelight. It turned out to be the swan song of San Francisco’s turn-of-the-century bohemians. Coppa tried to recapture the magic with several reincarnations of his cafe, but the bohemians had scattered.

Soon after Coppa abandoned his Monkey Block location, the wondrous murals were destroyed. They had lasted one year.

Gary Kamiya is the author of the best-selling book “Cool Gray City of Love: 49 Views of San Francisco,” awarded the Northern California Book Award in creative nonfiction. All the material in Portals of the Past is original for The San Francisco Chronicle. Email: metro@sfchronicle.com” style=”text-decoration: underline; color: rgb(65, 110, 210); max-width: 100%;”>metro@sfchronicle.com

Trivia time

Previous trivia question: What is the only planet besides Earth not to have a San Francisco street named after it?

Answer: Jupiter. (Pluto is also unnamed, but no longer considered a planet.)

This week’s trivia question: How many armed members of the Second Committee of Vigilance were there at its height?

Editor’s note

Every corner in San Francisco has an astonishing story to tell. Gary Kamiya’s Portals of the Past tells those lost stories, using a specific location to illuminate San Francisco’s extraordinary history — from the days when giant mammoths wandered through what is now North Beach to the Gold Rush delirium, the dot-com madness and beyond. His column appears every other Saturday, alternating with Peter Hartlaub’s OurSF.