The decision to approve the Hinkley Point nuclear power plant may raise scrutiny on Chinese investors that want to expand their atomic portfolio in the U.K.

The U.K. government will take a “special share” in all future nuclear projects giving it power to block changes in ownership that could impinge on national security, according to a statement on Thursday. For China, whose 33.5 percent ownership in Hinkley was the subject of security concern, the new rules may erect higher hurdles for reactor projects in Sizewell and Bradwell, which uses Chinese technology.

“The chance the Chinese are prevented from going ahead with Bradwell must be higher today than it was yesterday,” said Stephen Hunt, U.K. utilities analyst at Barclays Capital Services Ltd., in a phone interview.

The decision to tighten the rules highlights Prime Minister Theresa May’s security concerns about Chinese access to critical U.K. infrastructure. The 18-billion pound ($24 billion) Hinkley project is one-third funded by state-owned China General Nuclear Power Corp., which signed a deal in October with Electricite de France SA at Sizewell and another at Bradwell, both on eastern coast.

New Capacity

“We are delighted that the British government has decided to proceed with the first new nuclear power station for a generation,” China General said in a statement that reiterated its intent on “playing an important role in meeting the U.K.’s future energy needs.”

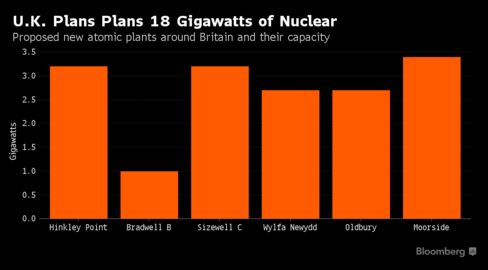

The U.K. wants to build 18 gigawatts of new nuclear capacity in the coming decades from about 9.4 gigawatts last year. The greenhouse-gas free energy produced by the reactors will be needed to replace aging fossil-fuel and atomic reactors removed from the grid and to keep the country’s climate change commitments. Government projections see nuclear covering a third of the country’s power needs by the 2030s at a cost of about 80 billion pounds.

The U.K.’s special share is unlikely to affect all investors equally, according to Barclays analyst Hunt.

“If you had European money, Japanese funding, or American money for example, the feeling is the government might be more sanguine,” he said.

assets.bwbx.io/images/users/iqjWHBFdfxIU/inMbJ9FGMKdI/v2/628x-1.png 628w, assets.bwbx.io/images/users/iqjWHBFdfxIU/inMbJ9FGMKdI/v2/750x-1.png 750w, assets.bwbx.io/images/users/iqjWHBFdfxIU/inMbJ9FGMKdI/v2/-1x-1.png 1200w” class=”” style=”max-width: 100%; margin: 0.5em auto; display: block; height: auto;”>

assets.bwbx.io/images/users/iqjWHBFdfxIU/inMbJ9FGMKdI/v2/628x-1.png 628w, assets.bwbx.io/images/users/iqjWHBFdfxIU/inMbJ9FGMKdI/v2/750x-1.png 750w, assets.bwbx.io/images/users/iqjWHBFdfxIU/inMbJ9FGMKdI/v2/-1x-1.png 1200w” class=”” style=”max-width: 100%; margin: 0.5em auto; display: block; height: auto;”> While the government won’t have a special share in Hinkley Point, it could still prevent EDF from selling its 66.5 percent stake during the construction, according to the statement. That veto power could prevent the company from reducing its share and bringing other investors into the project.

EDF would probably struggle to sell shares during construction, according to Martin Young, managing director of European utilities equity research at RBC Capital Markets. The European Pressurized Reactor has run into trouble at Olkiluoto in Finland, as well as Flamanville, France where costs have more than tripled to 10.5 billion euros ($11.8 billion) and construction is six years behind schedule.

“There’s no decent track record in building the EPR,” Young said. “Olkiluoto’s been a disaster, Flamanville’s been a little better. It’s not great.”

Once Hinkley is built, EDF may wish to sell its stake in order to release capital for further investment, replicating the model used by Dong Energy A/S and other offshore wind farm developers, said Young. At that point, the company would need approval from the government, according to the government statement.

Even then, the government may not “actually invoke such powers,” said Professor Jim Watson, director at the U.K. Energy Research Center, highlighting May’s decision in July not to intervene in the sale of ARM Holdings Plc to Softbank Group Corp.

“I can’t see any huge immediate impact for EDF and there’s no suggestion the financial terms of the deal have been revised.”