Photo from 1905 shows about where the Rome was scuttled some 50 years earlier, underneath the Alameda Exchange and the current-day Justin Herman Plaza. Photo from the SFMTA archive.

Directly underneath the bocce ball courts on the southern end of Justin Herman Plaza, at the foot of Market Street, there lay the remains of a large, three-masted ship called the Rome that arrived in San Francisco in 1850 and was purposely sunk two years later — as were many abandoned vessels — in order to create the basis for landfill upon which would ultimately be built the current Bay frontage of the city. 144 years later, in excavating the extension of the Muni Metro tunnel from Embarcadero Station above ground to Folsom Street in 1994, for what would become the K/T line, construction crews ran smack into the Rome, and determining that it was too large to be fully excavated, archaeologists removed what they could and the Muni tunnel was bored right through the sunken ship. The SFMTA is blogging this week about this fun bit of trivia, which first made national headlines in ’94 when the ship was found, and was picked up by the Chicago Tribune.

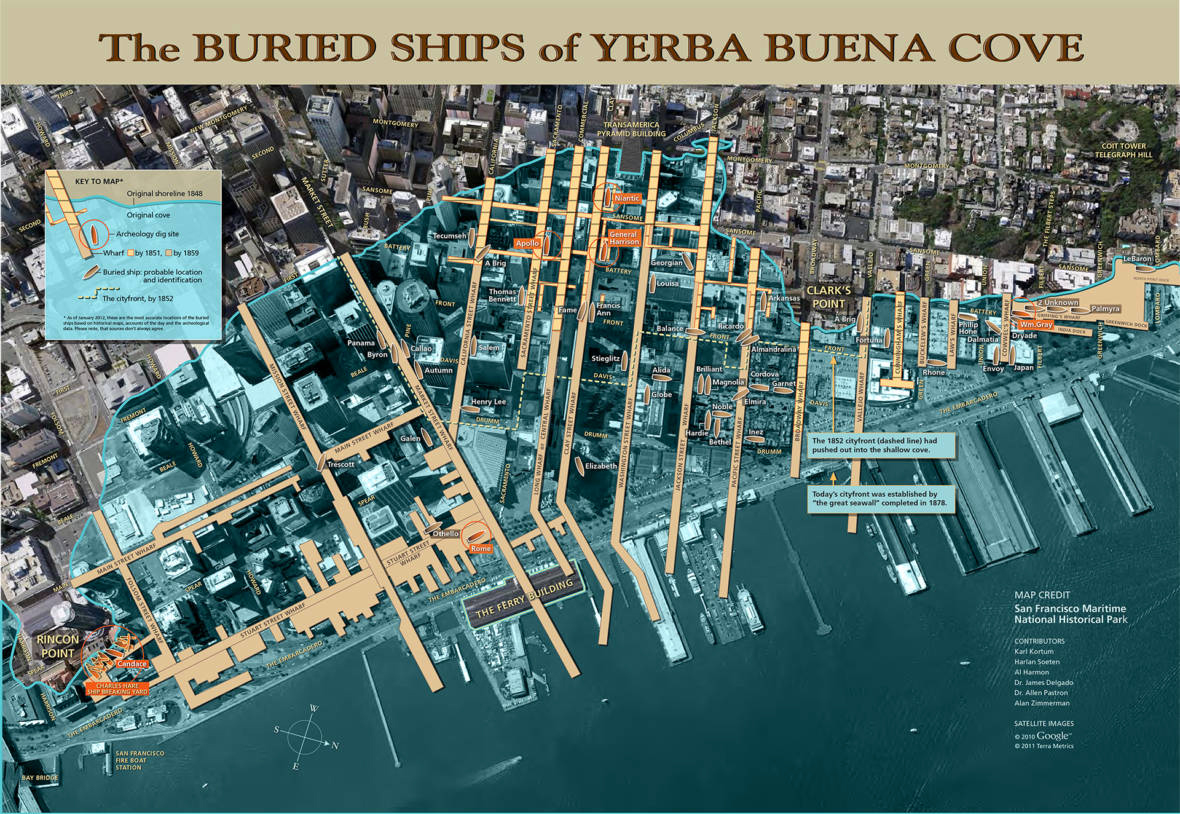

At the time the Rome was still seaworthy, this area was called Yerba Buena Cove, and the tip of Market Street was actually a long wharf that extended out over the water. In the map below you can see in blue where the original shoreline of the cove was, ca. 1848, as well as the location of the numerous ships buried beneath our streets — including the one under the Old Ship Saloon. Industrious early San Franciscans, in just those first couple years after the 1849 Gold Rush, rapidly filled the area in to create new real estate — and among the men who made their riches from doing so was Capt. Fred Lawson, who owned the Rome after it had sat for two years abandoned by its original crew, who like many thousands of others left their vessel behind when they ran off to the Sierra foothills to mine for gold.

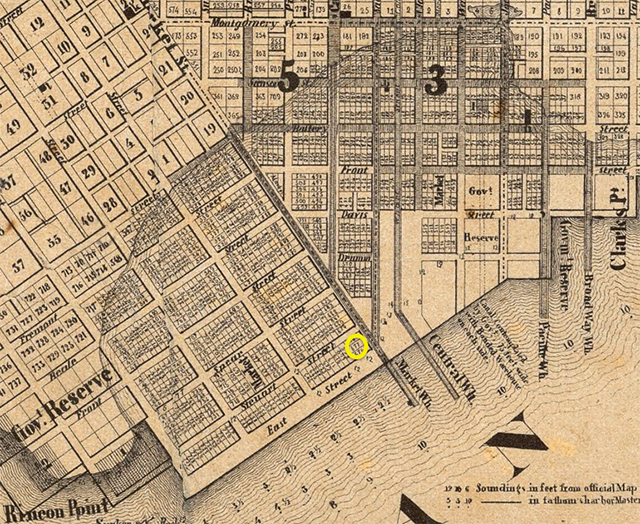

The 1852 map below, dug up by the SFMTA, also shows the former shoreline and shows just how much new real estate was created through man-made fill in a short period of time. The yellow circle shows the location of the Rome.

Project archaeologist James M. Allan uncovered the history of the ship on behalf of the SFMTA, and he told the Chicago Tribune at the time that Lawson “made quite a business out of scuttling abandoned Gold Rush hulks” to help would-be landowners “establish title to water lots by demonstrating an ‘improvement.'” Lawson himself, speaking to the San Francisco Examiner thirty-eight years later, in 1890, told the story this way:

“The ship Rome was a big Russian hulk that cost me about $1,000. She was used for a coal ship and sunk by me at the southwest corner of Market and East (now Embarcadero) Streets, under where the Ensign saloon was [then the Alameda Exchange in the photo above]. Her bow touches the edge of Market Street. I sank her for Joseph Galloway, and I had to do it in a hurry. Galloway bought a block of Smith [sic]. One morning he came running up to me and excitedly asked if I had a ship. I told him yes, that I had the Rome. He told me an injunction was to be served to prevent him having any more piles driven, but that if he could have the ship scuttled before 1 o’clock he would be all right. Before 1 o’clock my tow-boat took the Rome in to where he wanted it and down she went. I got $5,000 for that job.”

To put that in perspective, $5,000 would be worth over $150,000 in today’s dollars.

Sidebar: Niantic, creators of the stupidly popular Pokémon Go, is actually named after another one of these scuttled ships, which you can see on the map above just above Sansome, next to the Transamerica Pyramid.

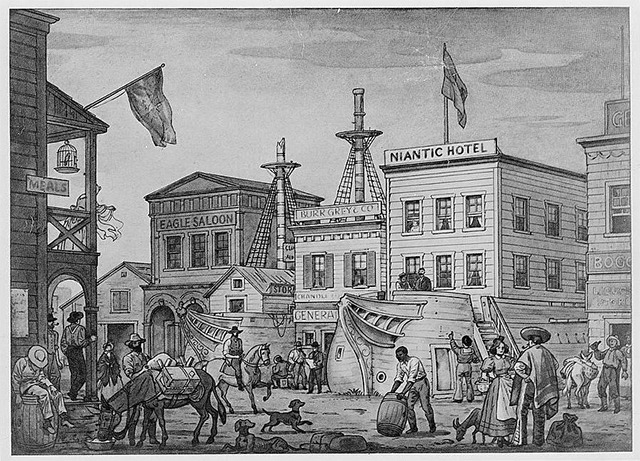

Below, via KQED’s recent history of these many scuttled ships, is an illustration from the Library of Congress depicting what the early streets of SF looked like in this era, as land was quickly filled in and hotels and saloons were built atop scuttled, partly submerged ships’ hulls, including the Niantic Hotel.

Illustration via the Library of Congress

Tunneling under this area near the present-day Embarcadero for what was called the Muni Metro Turnback Project (MMTP), workers and their boring machines ran directly into the hull of the Rome on December 2, 1994, and archaeologists were soon at work sifting through what they could find before the excavation could proceed. In the process, as the Tribune reported, they found various 1852 era detritus, all part of the trash heaps that helped create the landfill, like a soy sauce jar, a brass spoon, and a ceramic teapot.

So, now whenever you’re traveling inbound on the K/T line and the train is turning that corner toward Embarcadero Station, you can tell all your friends that you’re passing through the bow of a 161-year-old scuttled ship.

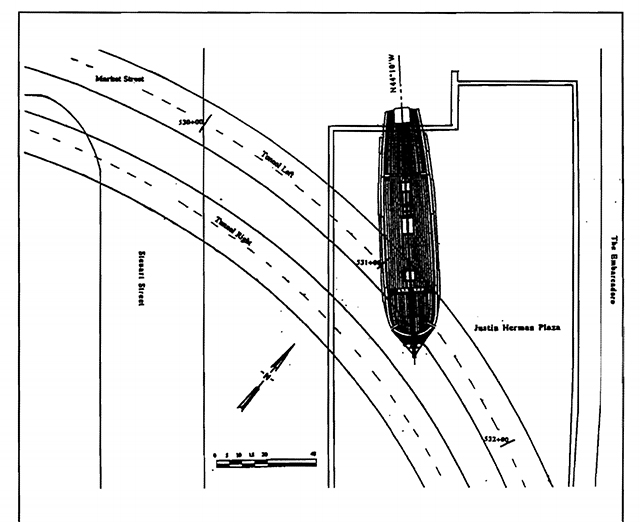

The illustration below, created by James Allan for his original report, shows just where the rest of the ship lies in relation to the tunnel.

Related: Rediscovered Historical Comics Recall San Francisco Days Of Yore