Postcard, circa 1957. The view is westward along Market Street from just below Powell. A Woolworth’s blade sign on the right marks the Flood Building.

Following the 1906 cataclysm, the stretch of Market Street between Powell and Polk developed as a lively theater and shopping district that by night was a sea of flickering chase lights and glowing neon tubes that seemed to stretch to the horizon on marquees announcing theater and cinema fare, and on towering blade signs like gigantic, fiery chart pins identifying each theater and department store along the broad and bustling thoroughfare; a protean street of dreams, alive with the pulse of the City.

Source: San Francisco History Center, S.F. Public Library

Fox Theater, opening night, 28 June 1929.

Source: San Francisco History Center, S.F. Public Library

Fox Theater Farewell Benefit, 16 February 1963.

When in 1963 the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency demolished the celebrated Fox Theater, a San Francisco landmark designed by Thomas Lamb on the corner of Polk and Market, it was replaced by high-rise apartments and commercial space covering the entire block of Market Street between Polk and Larkin, named Fox Plaza in memory of the theater. In 1964 BART began construction of its subway system, which for a decade turned downtown Market Street into a massive, gaping trench.

Source: San Francisco History Center, S.F. Public Library

The fenced-off, post-demolition pit at Polk and Market, 1964.

The destruction of the Fox was a death knell signaling the end of an era. The district lost much of its glamor when, under the 1967 Market Street Beautification Act, all of Market Street’s brightly-lit marquees and most of its neon blade signs were removed. When traffic was diverted away from the mid-Market area by BART construction, the district’s fate was sealed and it sank into a decline from which it has never recovered. Stores and theaters that had thrived for decades struggled on for awhile and then closed forever. Mid-Market became a constantly changing landscape of liquor stores, fast food outlets, porn shops, check-cashing companies and gaudy storefronts, few of which have survived more than a few years. The downturn in quality and character of mid-Market commerce and a profusion of unused buildings and boarded-up storefronts have obscured the district’s glorious past and left in its stead an oppressive hollowness and blight. Transience and decay have become ingrained, attracting derelicts, outcasts, and petty criminals from far and wide. One consequence of these changes, largely overlooked, has been a harsh decline in the quality of life for the area’s many long-time residents.

Source: San Francisco History Center, S.F. Public Library

Fads ‘n’ Fashions, 1969. For many Market Street enterprises, “Out of Business” became the sign of the times during BART construction.

Source: San Francisco History Center, S.F. Public Library

BART construction, Market and Eddy, 1971.

Marshall Square

(Updated 28 Apr 15.)

Source: California State Library

City Hall, circa 1900. As photographed from the rooftop of the bygone Mechanic’s Pavilion at Hayes and Larkin, the old City Hall is bounded in front by the diagonal slash of City Hall Avenue extending rightward to Leavenworth and McAllister from Larkin Street on the left.

Marshall Square was a plaza that connected Market Street with City Hall Avenue,* a parallel frontage road for the old City Hall. When the old City Hall was ruined by the 1906 earthquake and fire, the design for a new Civic Center demanded the reshaping of grid lines. City Hall Avenue was completely obliterated and Marshall Square became part of the Hyde Street extension to Market. Opened in 1926, the office building and theater at the corner of Hyde and Market is the namesake of Marshall Square, though nowadays it is known only by the name of its theater, the Orpheum.

*originally named Park Avenue.

Source: Bancroft Library, UC Berkeley

San Francisco Business District Map (detail), 1904. Marshall Square is circled in red.

Source: California State Library

City Hall, circa 1897. Shot from Eighth Street just below Market, this view looks straight across the Pioneer Monument in the middle of Marshall Square to the old City Hall. Crowning its Baroque dome is the Goddess of Progress, an iron statue with a corona of electric light bulbs.

Designed piecemeal by seven different architects; shoddily constructed with compromised materials over a period of twenty-seven years at a cost of six million dollars; the old City Hall was a disgraceful mess, the malodorous* embodiment of municipal graft. Nine years after its completion, it was all but destroyed by the 1906 earthquake and fire.

*The stench of raw sewage frequently permeated the superstructure’s poorly ventilated chambers and corridors; a consequence of faulty plumbing.

Source: California State Library

City Hall Avenue, 1899. Looking northwest from atop the Odd Fellows Building at Seventh and Market, we see the east end of City Hall Avenue intersecting with McAllister and Leavenworth Streets, opposite the Hall of Records on the left.

Source: San Francisco History Center, S.F. Public Library

Pioneer Monument, Marshall Square, 1906. A view looking north, with the ruins of the old City Hall in the background.

Built in 1894 with money bequeathed by real estate magnate James Lick, sculptor Frank Happersberger’s Pioneer Monument mythologizes the story of San Francisco’s supposed “manifest destiny.” As told by the empire builders themselves,* it is an unabashedly romanticized story of empire building that depicts Native Americans as a docile and subservient people conquered by the Argonauts, nom de guerre of pioneering gold miners. Contrary to both reality and Lick’s final wishes, the monument also places Mining ahead of Agriculture in order of importance, if not sustainability. Taken from the Great Seal of California, the figure that crowns the monument is Minerva, Roman goddess of wisdom and sponsor of arts, trade and technology. As a goddess born fully-grown, she symbolizes California’s direct attainment of statehood without first becoming a U.S. territory.

*Lick was a founder of the ultra-exclusive Society of California Pioneers.

Source: San Francisco History Center, S.F. Public Library

City Hall Avenue, 1910. Looking southwest from Leavenworth Street, all that remains of the old City Hall is the domed Hall of Records, which was finally razed in October 1916 by the Dolan Wrecking Company.

Source: California Digital Newspaper Collection

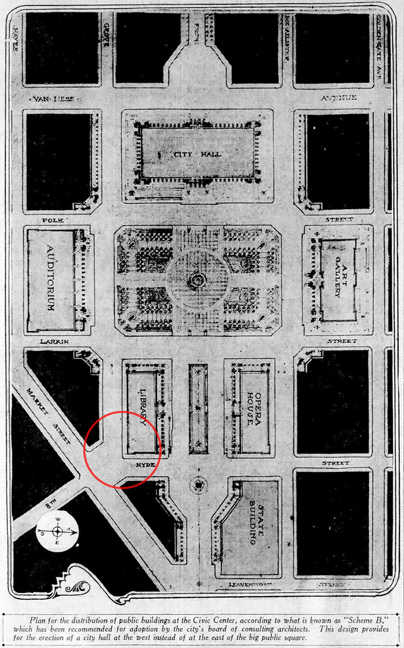

Illustration, San Francisco Call, 29 May 1912. “Scheme B” plan for the Civic Center. Chaired by John Galen Howard, the consulting architects included Frederick H. Meyer, and John Reid, Jr. Note the extension of Hyde Street, where the site of Marshall Square has been circled in red. Also of interest are the proposed sites for a library, art gallery, opera house and state building.

As things turned out, City Hall and the Civic Auditorium were the only Civic Center structures completed by 1915, just in time for the opening of the Panama Pacific International Exposition. The Civic Auditorium was in fact specifically designed for the PPIE and is one of the few exposition buildings still remaining. It was renamed the Bill Graham Civic Auditorium in 1992, in memory of the City’s renowned concert promoter. The beaux-arts Main Public Library was built in 1917 on the site proposed for the opera house. Following extensive remodeling under the direction of Italian architect Gae Aulenti, the building became home to the Asian Art Museum in 2003. The new Main Library, erected 1993-95 and opened in 1996, was built on the site originally proposed for a library. 1922 saw the opening of the California State Building at 350 McAllister, proposed site of the art gallery. Today, the beaux-arts granite structure is home to the Supreme Court of California. Opened in 1932, both the beaux-arts War Memorial Opera House and its twin sister, the War Memorial Veteran’s Building (home to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art until 1994), were constructed on Van Ness Avenue, opposite City Hall. The site proposed for a state building, now part of the United Nations Plaza, is where the beaux-arts Federal Office Building was constructed between 1934 and 1936.

As composed of these seven beaux-arts buildings, the San Francisco Civic Center is widely considered as one of the most successful manifestations of the City Beautiful Movement. Listed in the National Register of Historic Places in October 1978, it was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1987.

“City Hall” (2011)

“Civic Auditorium” (2011)

“Asian Art Museum” (2011)

Source: Bancroft Library, Jesse B. Cooke Collection

Market and Eighth, 1912. The view is to the northeast along Market Street as photographed from the southwest corner of Eighth Street, opposite Marshall Square. On the left is the Hall of Records on City Hall Avenue.

Source: Bancroft Library, Jesse B. Cooke Collection

Marshall Square, 1914. When this photograph was taken, Marshall Square and City Hall Avenue were little more than artifacts of former times. The old City Hall had been demolished and construction of the new City Hall and Civic Auditorium was nearing completion. Together with its associated infrastructure and architecture, City Hall Avenue was anomalous to the evolving urban fabric. Soon, every trace of it would be expunged. Marshall Square as a plaza would also disappear, though its eastern pavement would endure as part of the Hyde Street extension. The Pioneer Monument remained in place until 1993, when it was moved to the orphaned block of Fulton Street between Hyde and Larkin, to make way for the new Main Library.

Source: San Francisco History Center, S.F. Public Library (R.J. Waters & Co.)

New City Hall, circa 1915. Looking south from Larkin and McAllister, the new Civic Auditorium is in the background to the left. The block-long excavation in the foreground marks the site of the California State Building, opened in 1922.

“Asian Art Museum and Federal Buildings” (2008)

“Old Federal Office Building” (2008)

Now occupied by the General Services Administration, the old Federal Office Building was constructed on the site of the former Hall of Records. In 1975, the building became an integral part of the newly-constructed UN Plaza, a 2.6 acre pedestrian mall designed by Lawrence Halprin to commemorate the 1945 signing of the United Nations Charter at the War Memorial Opera House. The plaza was rededicated by visiting members of the UN General Assembly in 1995. Following much-needed renovations, it was again rededicated during World Environment Day in 2005. The new Federal Office Building is on Mission, across Seventh Street from the Ninth Circuit Appellate Court.

“Bolivar Monument” (2006)

At the west entrance to the United Nations Plaza, aligned with the Pioneer Monument and City Hall, stands a monument to Simon Bolivar, the founder of Bolivia and liberator of Columbia, Ecuador, Panama, Peru and Venezuela. Dedicated on 06 December 1984 by Dr. Jaimie Lusinchi, President of Venezuela, the monument is a copy of Adamo Tadolina’s original nineteenth-century sculpture that stands in the Plaza del la Constitucion in Lima, Peru. On the left of this photo is the new Main Library.

“UN Plaza Farmers Market” (2008)

One of the nicest things to flourish in the central city in more recent years is a farmers market, which takes over the United Nations Plaza every Wednesday, Friday and Sunday.

“Produce Stand” (2008)

“Flower Stand” (2008)

Source: Bancroft Library, UC Berkeley

Marshall Square Building, 1926. Until the early 1990s, the Marshall Square Building’s storefront arcades were occupied by a pharmacy on the corner and various small businesses that added much to the character and color of Market Street. One business I particularly remember bore the name of its proprietor, “Mister San Francisco,” a dapper fellow with an extraordinarily long, waxed, and elaborately curled Snidely Whiplash mustache, who conducted off-the-beaten-path tours of the local night life.

Source: Bancroft Library, Jesse B. Cooke Collection

Marshall Square Building, 1928. Revealed in this view is a corner of the Pioneer Monument at the foot of the Hyde Street extension on the left.

After the Marshall Square Building was purchased by its current owners, tenants were forced to leave, some sooner than others. Last to go was the corner pharmacy. While the theater thrived, the Marshall Square Building itself was neglected; characterized by darkened storefronts, empty save for odd bits of debris left behind by departed businesses. By the time the Pioneer Monument was moved to Fulton Street, every storefront was vacant and soon would be sealed and stuccoed-over. Where once were variety and commerce, there now are anonymous windows and blank wall, prosaic and drear. Marshall Square has already faded from civic memory, and with antecedents thoroughly obscured, its namesake is only known as the Orpheum Theater.

“Marshall Square Building” (2011)

“Orpheum” (2008)

1192 Market Street. Marshall Square Building; office building, theater, and storefronts. 4B stories, steel frame and concrete construction; cast concrete and stucco facade, two-story bays with casement windows and spandrels; three-part vertical composition; Spanish Moorish/Spanish Baroque design. Alterations: remodeled theater entrance; new blade sign and marquee; decorations stripped from spandrels; finials removed; storefronts filled in and stuccoed. Current owner: Shorenstein Hays Nederlander Organization. Architect: B. Marcus Priteca. 1926.

Christened the Pantages when it opened in 1926, the theater was designed as a vaudeville house to replace the original Pantages Theater at 939 Market Street. A few years later, it was sold to RKO and soon thereafter reopened as the Orpheum, a first-run movie house. From the premiere of This Is Cinerama! on Christmas Day 1953 until the final showing of Ice Station Zebra early in 1970, the Orpheum was San Francisco’s foremost Cinerama cinema. The theater was closed for a short time and then reopened in 1977 as a venue for live theater, but the conversion was unsuccessful and the theater was closed once again. It was purchased in 1981 by the Shorenstein Hays Nederlander Organization and since then has been a successful showcase for traveling Broadway shows.

Source: San Francisco History Center, S.F. Public Library

Orpheum Theater, 1931.

Source: San Francisco History Center, S.F. Public Library (Photo: Larry Moon)

Orpheum Theater, 1962.

National Hotel

“National”

National Hotel. 1139 Market Street

Erected in 1906, the National Hotel is typical of rooming houses built to house a maximum number of occupants in a small space. There are storefronts at street level, while the hotel occupies the second and third stories. The building is long and narrow, with forty-five roughly 10′ by 10′ rooms on each floor. There is no lobby, the entrance to the hotel being a stairway that leads directly to the second floor, where a small room with a teller’s window serves as the hotel office. The rooms have small sinks and case closets, with windows that open onto narrow light wells providing room ventilation. Bathrooms are located in the back of the building. Monthly rent in 2006 was $600, about average for SROs at the time.

Strand Theater

“For Sale”

Strand Theater (formerly the Jewel, 1917; Sun, 1920; College, 1920; Francesca, 1921). 1127 Market Street.

National Hotel. 1139 Market Street

Source: San Francisco History Center, S.F. Public Library

Strand Theater, circa 1945.

Named the Jewel when it first opened October 1917 as part of the Grauman chain, the theater saw its name change, along with its management, several times over the next decade. When it was renamed the Strand in 1928, the name stuck, and so it remained until the very end. Operated by the West Side Theater Company from 1940 to 1977, the programming was triple bills, changed daily, with nightly bingo games. In 1977, the theater was purchased by Mike Thomas, who around the same time also acquired the Warfield, Crest and Embassy theaters. Thomas remodeled the Strand and hired security to keep out undesirables, then reopened the theater with a revival of Howard Hughes’ 1943 production of The Outlaw. The show was a sell-out and the Strand soon became known as a venue for revival cinema, hosting occasional guest appearances by such celebrities as Lana Turner, Sophia Loren and Mae West. The theater was also known for its midnight showings of The Rocky Horror Picture Show.

Source: San Francisco History Center, S.F. Public Library (Photo: Alan J. Canterbury)

Strand Theater, 1964.

Market Street commerce, which had begun to decline in the mid-60s, took a sharp downward turn in the 1980s and, with the increasing popularity of home video, the revival cinema business declined as well. The theater was closed following the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake and then reopened under the management of Silver Screen Amusements. Following a brief closure in June 1997, the Strand reopened as a porn theater, showing projected video. In its final years, it was a haven for drug dealers and prostitutes. Early in 2003, after a raid by the San Francisco Police Department, the Strand was closed once again, this time for good.

Embassy Theater

“Embassy Site”

Embassy Theater Site (American Theater, 1907; Rialto, 1916; Rivoli Opera House, 1923; Embassy Theater, 1927; Warner Brothers, 1932-1933). 1125 Market Street.

Source: San Francisco History Center, S.F. Public Library

Embassy Theater, 1927.

Although the theater’s construction was interrupted by the 1906 earthquake and fire, it nevertheless opened the following January as the American Theater. After a couple of name changes over the next two decades, it was named the Embassy in 1927 when it premiered Vitaphone Talking Pictures. The theater was briefly known as Warner Brothers in the early ’30s, but its name soon reverted to the Embassy. Much later, under the management of Dan McLean, it was a popular second-run Market Street cinema that highlighted nightly games of Ten-O-Win, a spin-the-wheel game originated by McLean.

Source: San Francisco History Center, S.F. Public Library

Embassy proscenium and orchestra, undated.

During the 1980s, the Embassy suffered much the same fate as the Strand, becoming a harbor for drug dealers, prostitutes and the homeless. The theater was condemned after suffering severe structural damage in the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake and was finally demolished in 1994. A popular source of entertainment for several generations of San Francisco theatergoers, the Embassy is unique in the annals of San Francisco cinema as the only theater to have been shaken by both the 1906 and 1989 earthquakes.

Source: San Francisco History Center, S.F. Public Library (Photo: Alan J. Canterbury)

Embassy Theater, 1964.

Odd Fellows Temple

“Odd Fellows”

Odd Fellows Hall. 26 Seventh Street. Five stories. Steel frame construction, brick and terra-cotta facade, three-story galvanized iron windows, galvanized iron cornice. Architect: George Andrew Dodge. 1909.

From the time I first laid eyes upon this building, I have admired it; partly for its dramatic, ornate windows, partly for its name, Odd Fellows, and partly for the wonderful two-and-a-half story terra-cotta panel illustrating the Odd Fellows’ symbols. Formerly the Grand Lodge of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows, this unusual building was built as a replacement for the original lodge that was destroyed during the 1906 earthquake and fire. While their Grand Lodge is now in Saratoga, California, several Odd Fellows lodges still meet here, including the Yerba Buena Lodge #15 and Apollo Lodge #123.

Source: Bancroft Library, U.C. Berkeley

Odd Fellows Hall, 1886.

Source: Bancroft Library, U.C. Berkeley

Odd Fellows Hall, 1906. The collapsed roof of the original hall is clearly visible in this photo, taken from Leavenworth near Golden Gate on the morning of the ‘quake.

Source: Bancroft Library, U.C. Berkeley

Odd Fellows Hall after the fire, 1906.

Source: Bancroft Library, U.C. Berkeley

Odd Fellows Hall dynamited, 23 April 1906. Five days after the fire, the dangerously unstable shell of the Odd Fellows Hall was dynamited with 750 pounds of explosive. Unfortunately, the poorly placed charges left much of the building standing, but the blast nearly destroyed the main Post Office a half-block away at Seventh and Mission.

“IOOF Windows”

Odd Fellows Hall. 26 Seventh Street.

In need of repair and a paint job, the Odd Fellows’ elaborate windows show the building’s age. In the background are the U. N. Plaza fountain and the old Federal Building.

Looking closely at this photograph, you will note in a window at the very bottom a sign proclaiming the end is near. Another sign indicates that this corner of the building is the studio of one Richard L. Perri. Both of these signs have been there for as long as I can remember, and as I have always relished dark humor, I often wondered who this Mr. Perri could be. At last, near the beginning of 2008, I met Richard when I was invited to a meeting of the Yerba Buena Lodge of the Odd Fellows. There, I discovered him to be a most charming and witty fellow, who was delighted to know that for years I had been an admirer of his sign.

Grant Building

“Early Morning – Market Street”

The Grant Building and Odd Fellows Hall are seen in this late autumn view, taken around seven o’clock in the morning.

“Grant Building”

Grant Building. 1095 Market Street. Owner: Seligman Western Enterprises. Nine stories. Steel frame construction; pressed brick facade, sandstone lintels and keystone, galvanized iron parapet, double-hung sash. Architect: Newton Tharp. 1904.

The Grant Building is one of the very few large buildings on Market Street to have survived the 1906 earthquake and fire. Although it has been upgraded over the years, the original interior marble finishes and beautiful cast iron staircases have been preserved. The building has for years been the home of numerous non-profit organizations, including the San Francisco Study Center, which publishes a monthly neighborhood paper, the Central City Extra.

Source: California State Library

Grant Building, 1906.

Source: Bancroft Library, U.C. Berkeley

Merrill’s Drug Store, circa 1949. Closed since 2003, Merrill’s was a friendly, local pharmacy favored by central city residents.

Imperial Theater

“Market Street Cinema”

Market Street Cinema (Grauman’s Imperial, 1912; Imperial, 1916; Premier, 1929; United Artists, 1931; Loew’s, 1970; Market Street Cinema, 1972). 1077 Market Street. Architect: Cunningham and Politeo.

Source: Bancroft Library, U.C. Berkeley

Imperial Theater, 1919.

One of many links in the Grauman’s chain, the theater opened as Grauman’s Imperial on 22 December 1912. Known as the Premier for a short time in the late ‘20s, in 1931 it became the United Artists Theater, a first-run movie house, and so it remained until 1970, when the theater was briefly taken over by Loews. In 1972, the theater was renamed the Market Street Cinema, shortly thereafter becoming a venue for adult films, which in the ‘90s gave way to live entertainment and lap dancing.

Source: San Francisco History Center, S.F. Public Library (Photo: Alan J. Canterbury)

United Artists Theater, 1964.

Guild and Centre Theaters

“Guild and Centre Theater Sites”

Guild Theater Site (Egyptian Theater, 1924; Studio Theater, 1943; Guild Theater, 1947; Pussycat Theater, 1974). 1069 Market Street.

Centre Theater Site (Round Up Theater, 1944; Centre Theater, 1947). 1071 Market Street.

First named the Egyptian, the theater opened with The Last Man on Earth on 14 March 1925. Catering primarily to the Market Street walk-in trade, the theater showed low-priced, late-run releases until Christmas Eve 1943, when it was reopened as the Studio and, as a lure to on-leave servicemen, programming was changed to more sensational, B-movie fare. On 6 June 1947, the theater became the Guild, showing the first-run re-release of MGM’s The Great Waltz, which ran for two months, followed by a three-month run of the first major re-release of Gone with the Wind. At the end of 1947, the theater started showing low-priced, late-run action films, ultimately providing three features for fifty cents. Around 1970, the theater started showing adult films and was renamed the Pussycat in 1974. Along with the Centre, it closed late in 1987, and was afterward converted to retail space.

Source: San Francisco History Center, S.F. Public Library (Photo: Alan J. Canterbury)

Guild and Centre Theaters, 1964.

Opened first as the Round Up on 12 February 1944, the theater offered a program of double-feature Westerns, which changed daily. After it was renamed the Centre in 1947, it showed a hodgepodge of action films and re-releases until 1949, when it began to specialize in comedies, showing a single feature with assorted cartoons and short subjects in programs that changed weekly instead of daily. The tiny theater, which had a single aisle with rows of five seats on either side, was the quintessential “shooting gallery,” a theater type named for its long and narrow layout. When widescreen cinematography became the rage in the early ‘50s, the Centre’s narrowness prevented the theater from adapting its screen to the new format. It survived instead by changing its programming to adult films, which it showed until its closing in 1987. The theater has since then been converted to retail space.

Callaghan Building

Source: San Francisco History Center, S.F. Public Library

Market near Seventh, 1925. A sign for the Egyptian Theater is visible behind the Imperial Theater on the right. The long, two story building on the left is the Callaghan Building.

“Sunset – McAllister and Market”

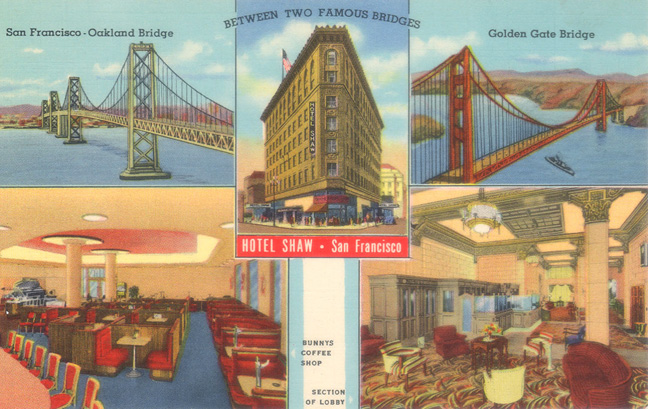

One of several flatiron buildings to be found along the north side of Market Street, the Renoir Hotel began its life in 1907 as a two-story office building named the Callaghan Building (originally built in 1904 and reconstructed after the earthquake and fire). When five more stories were added on in 1936, the building was converted to a hotel named the Shaw, which had such amenities as a street-level lounge and barbershop. Following a couple of name changes in the ’80s, in 1993 the hotel was purchased and renamed the Renoir by Regent West LLP.

Source: Bancroft Library, U.C. Berkeley

Market and McAllister, 1906. Here photographed just months after the earthquake and fire, the Callaghan Building’s reconstruction was already well underway. On the right is the newly-restored Hibernia Bank Building at 1 Jones Street, and in the background are the skeletal ruins of the old City Hall on City Hall Avenue.

Postcard, Hotel Shaw, circa 1945.

Hibernia Bank

“Fallen from Grace”

Hibernia Bank Building. 1 Jones Street.

The Hibernia Bank was first organized in April 1859, in a little office at the corner of Jackson and Montgomery. Among the first depositors were Irish miners who had struck pay dirt in the California goldfields to the north. The Hibernia Bank accepted the miners’ unminted gold and earned a reputation among them for courteous and efficient transactions, and eventually became known as “the people’s bank.” Business increased apace and before long the bank moved to more spacious quarters at Montgomery and Post, but the institution’s extraordinary growth over the next two decades eventually demanded another change.

It was a fateful day when the Hibernia’s directors hired a relatively unknown architect named Albert Pissis to design a new building at the corner of McAllister and Jones. Completed in 1892, the Hibernia Bank Building captured the hearts of San Franciscans and ensured the fame of Albert Pissis, whose work would change the face of San Francisco in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Architect and Engineer reflected in 1909 that

. . . the (Hibernia Bank) became famous at once and marked an epoch in San Francisco architecture and placed its designer in the forefront of his profession, where he has remained ever since.

Indeed, so famous was the building that San Franciscans called it “The Paragon.” The Hibernia Bank was one of the few buildings in the central city to survive the 1906 cataclysm, although it was damaged by the fire. As one of the City’s most popular and vital institutions, it was also one of the very first buildings to be restored.

Source: San Francisco History Center, S.F. Public Library

Market and Jones, 1891. Dominating the photograph is the Murphy Building, home of Prager’s Dry Goods; on the left is the Hibernia Bank Building, still under construction.

Source: California Digital Newspaper Collection

Illustration, San Francisco Call, 15 September 1892. Shortly after the new bank building was completed, the San Francisco Call asked twenty San Francisco artists, “From an artistic point which building do you think the best?” Fourteen of the artists named the Hibernia Bank Building; the Mills Building came in a distant second with four votes, followed by the Crocker and Mutual Life Buildings with one vote apiece. The results of the poll were published in an article that declared the Hibernia Bank was “The Most Artistic Building in Town.”

“Hibernia”

After it was vacated by the Hibernia Savings and Loan Company, the building served as headquarters for the San Francisco Police Department Tenderloin Task Force until the new Tenderloin Station was finally completed in 2000. An out-of-town speculator then bought the building and left it empty and unmaintained. This prominent landmark, which should be a proud San Francisco showpiece, has for years been a focal point of neighborhood blight.

Source: Bancroft Library, U.C. Berkeley

After the fire, 1906. The pile of rubble in the foreground is all that remained of the Callaghan Building; on the right are the ruins of the Murphy Building.

Source: Bancroft Library, U.C. Berkeley

Fire-damaged Hibernia Bank, 1906. When this photo was taken, restoration of the bank building had just begun.

Source: Bancroft Library, U.C. Berkeley

Officers and employees of the Hibernia Bank, 1906. Clearly none with whom to trifle, these gentlemen protected the Hibernia’s compromised bank vaults during the height of the fire.

Source: Bancroft Library, U.C. Berkeley

Opening Day, 25 May 1906. Just five weeks after the fire, while the building’s restoration was still in progress and before much of the City’s reconstruction had even begun, the Hibernia reopened to five-block-long lines of depositors in desperate need of funds.

Hibernia Grillwork

The Hibernia Bank Building holds an unparalleled place in San Francisco history. It is truly an architectural treasure, but one that has been sadly forgotten, and thus the building’s exterior has suffered greatly from years of neglect and abuse. Near the end of 2008, the building was purchased for $3.9 million by Seamus Naughten, who also owns the old KGO-TV building on Golden Gate Avenue. More than two years later, the building continues to rot and its future remains uncertain.

Hibernia Dome and Balustrade

Paramount Theater

Source: San Francisco History Center, S.F. Public Library

Granada Theater, opening day, 1921. The Boyd Hotel and part of the Hibernia Bank Building are visible on the far left; in the background to the right is the steel skeleton of the Golden Gate Theater, under construction at Golden Gate and Taylor. The large, three-story building at the corner of Jones and Market is Prager’s Department Store.

Designed by Alfred Henry Jacobs, this opulent movie palace opened in 1921 under the Publix banner as the Granada Theater. It had a four manual, thirty-two rank Wurlitzer organ and boasted an operating staff of 122 people. After becoming a part of the Fox chain for awhile, the theater was returned to the Publix fold and on 31 January 1931, after extensive remodeling, was reopened as the Paramount.

Source: San Francisco History Center, S.F. Public Library

Granada Theater, circa 1923. This beautiful nighttime image imparts a dreamlike quality to the Granada Theater’s fanciful architecture, which is reflected in the cupola of the nearby Golden Gate Theater.

Source: San Francisco History Center, S.F. Public Library

Paramount Theater, 1930. A view from the loge of the newly remodeled theater.

Source: San Francisco History Center, S.F. Public Library

Paramount Theater after remodeling, 1930.

Source: San Francisco History Center, S.F. Public Library

Paramount Theater, circa 1945.

Source: San Francisco History Center, S.F. Public Library (Photo: Alan J. Canterbury)

Paramount Theater, 1964.

“Post-mortem”

Paramount Theater Site. 1066 Market Street.

When the Shorenstein Company demolished the Paramount Theater in the late 1960s, two small storefronts were hastily erected to plug the resulting gap between adjacent buildings. Incongruous, commonplace, and cheaply made, they are emblematic of the poor planning that helped to catalyze the district’s downfall.

Pompeii Theater

“Regal”

Unoccupied storefront (formerly Pompeii Theater, Regal Theater, Bijou Theater, L A Gals). 1046 Market Street. 1925.

Opened in mid-1925 as the Pompeii, the theater was renamed the Regal on 8 February 1936. For some thirty years, the Regal was one of several popular small Market Street cinemas that catered to the walk-in trade, showing for a very low price action films that were changed four times a week. In the mid-50s, double features became triple features and six color cartoons were included with every program. In 1972, the theater started showing hardcore films. When the Mitchell Brothers took it over in 1974, it was renamed the Bijou, then later renamed the Regal once again before it finally devolved into a lap dancing venue named LA Gals.

Heart of the City

“Heart of the City”

Once the prosperous heart of San Francisco’s theater district, Mid-Market has become a blighted no-man’s-land of empty buildings and frowzy storefronts. Many of the storefronts are boarded up, and those that are not have been so often remodeled that nothing is left of the original design; however, look upward and the architecture still appears much the same as it did almost a century ago. Above the storefronts one sees the designers’ original intent, and the architecture’s true character is revealed. Designed to celebrate and embrace the human spirit, it is also accessible, built on a human scale.

“Mercantile Block”

In 2005, the former Weinstein Company department store was given a bright blue facade and converted to live/work lofts, most of which are still empty in 2009.

Source: San Francisco History Center, S.F. Public Library

Weinstein Company department store, 1950. Newscopy: “THE NEW LOOK AT 1041 MARKET ST. – Exterior view of the Weinstein Company main store at 1041 Market street, as it appears today following recent remodeling. The just inaugurated motorstairs, conveying to and from all floors, in the store climaxes extensive interior remodeling and improvement.”

“Tawdry Storefronts”

How far this remarkable street has fallen! At one time a source of civic pride, Mid-Market has become San Francisco’s badge of shame. Surely the angels weep for its passage through neglect into oblivion.

“Vacant Buildings”

“Fascination”

Fascination Site. 1027 Market Street.

Fascination was a unique Market Street business that first opened its doors in the 1950s and closed them for the final time in 2003. It was a kind of midway arcade game located on the main thoroughfare of San Francisco. The fact that Fascination was a successful business for all those years is an indication of the steady, if not devoted patronage of its clientele, who were almost exclusively the tenants of surrounding SROs after BART construction disrupted Market Street commerce (see also “Daybreak” in Part I: Sixth Street).

Eastern Outfitting Company

“Grand Illusion”

1017-1021 Market Street, Eastern Outfitting Company. 7B stories; brick and steel-frame construction; white sandstone facade; casement windows framed by huge terra-cotta Corinthian order columns; galvanized iron entablature with “Furniture and Carpets” in relief. Architect: George Applegarth. 1909.

I remember wishing I could levitate upward and in through the open window above me when I captured this image. As often as I have photographed this building’s exterior, I have never been able to gain access to the upper floors. The little round holes in the window casings are light sockets, 700 to be exact, which unfortunately have not had light bulbs in them for many years.

Source: California Digital Newspaper Collection

Clippings from the San Francisco Call. (left) 05 September 1909. (right) 26 January 1911.

Following the opening of its first store at 1310 Stockton in 1899, the Eastern Outfitting Company did such a bang-up business that in January 1903 the company opened a new store in a much larger building at 1320-1328 Stockton. When that building was destroyed by the 1906 fire, the company set up temporary post-fire quarters at 1970 Mission Street. By the time the company opened its brand new store at 1017-1021 Market Street on the evening of 05 September 1909, the Eastern Outfitting Company had branches scattered throughout California and the new building became headquarters for the chain. At the grand opening, the store was flooded by a throng of customers and well-wishers, and over a hundred floral arrangements from friends and competitors alike were distributed throughout the new building’s corridors. The employees celebrated by presenting an appropriately engraved bronze plaque to the management.

In the late 1940s, the building became the Union Furniture Store. In more recent years, sweatshops have occupied the upper floors and the storefront has been leased by a succession of short-lived bargain stands.

Postcard, circa 1909.

Source: San Francisco History Center, S.F. Public Library (Photo: Alan J. Canterbury)

Circa 1964.

“Furniture and Carpets”

The Eastern Outfitting Company Building is close to where Market Street intersects with Sixth Street, Golden Gate Avenue and Taylor Street. The upper stories of a building in the foreground are part of the San Cristina residential hotel. The ground floor is currently occupied by Show Dogs, the most recent in a succession of restaurants. The building is also where Christian Slater interviewed Brad Pitt in Interview with the Vampire. It is a flatiron building, designed to fit the acute angle of Market Street intersecting Golden Gate Avenue. What appears to be a turret-like structure is actually just the narrow tip of the triangle.

“Billiards, Furniture and Carpets”

From a Market Street sidewalk perspective, the Eastern Outfitting Company Building’s enormous, unrelieved expanses of brick are mostly hidden by the buildings on either side. The illusion created by the false front is largely dependent on looking upward from street level. The giant Corinthian order columns and capitals are constructed of terra-cotta tiles; and the entablature, seemingly so massive, is in fact hollow—a galvanized-iron box. Architecture like this is for me transcendent; it turns the street into a stage set, which makes otherwise hidden parts of the building even more tantalizing. The deus ex machina, you might say, is the utilitarian brick that makes up the building behind the facade.

Across Market Street from the Eastern Outfitting Company Building, the rough brick wall advertising Hollywood Billiards used to abut the beautiful Paramount Theater, which was razed by the Shorenstein Company to make way for . . . a parking lot.

Golden Gate Theater

“Where the Tenderloin Begins”

On the left is the San Cristina residential hotel, and in the background behind the streetlight is the McAllister Tower. In the center are the spires of St. Boniface, a block-and-a-half away on Golden Gate Avenue; to the right are the entrance and marquee of the Golden Gate Theater.

“Lansburgh’s Legacies”

Golden Gate Theater. 1 Taylor Street.

Warfield Building. 988 Market Street.

Now mostly empty, the Golden Gate Theater and the Warfield Building were designed by G. Albert Lansburgh, one of the great American theater architects of the Twentieth Century. Raised in San Francisco, Lansburgh worked for both Bernard Maybeck and Julius E. Krafft while studying at U.C. Berkeley. After graduating, he moved to Paris and studied at the prestigious Ecole des Beaux-Arts. Upon earning his diploma in 1906, he returned to San Francisco one month after the city’s devastation by earthquake and fire, and lived here throughout his long and illustrious career.

“Golden Gate Theater”

Golden Gate Theater. 1 Taylor Street. Eight stories; dome, arcaded top story, brick and fine terra-cotta facade, wrought-iron balconets. Entry and marquee altered, storefronts boarded shut. Owner: Shorenstein Hays Nederlander Organization. Architect: G. Albert Lansburgh. 1922.

The Golden Gate Theater stands at one of the busiest entries to the Tenderloin. Featuring vaudeville, the theater first opened its doors in 1922. Over the years, theatergoers saw everything from the Marx Brothers to Cinerama. Most recently, it has been a venue for Broadway shows, including Rent, the film version of which was shot less than a block away on Sixth Street. Programming since 2006 has been sporadic and the theater often sits empty and unused for months at a time.

Source: San Francisco History Center, S.F. Public Library

Golden Gate Theater, circa 1923.

The theater’s owner, scion of one of San Francisco’s wealthiest families and the City’s largest owner of downtown commercial properties, has boarded up storefronts along Taylor Street and Golden Gate Avenue that once housed colorful theater-related businesses. The owner has kept the office space at 25 Taylor vacant since evicting an entire building of non-profit organizations in 1995. The terra-cotta and wrought-iron details of this Art Deco palace have suffered greatly from neglect and the six-story neon signs haven’t worked in ages. The building’s rundown, semi-abandoned aspect and the interdiction of small business have both suppressed neighborhood commerce and proliferated blight.

Warfield Theater

“Warfield”

982-998 Market Street, Warfield Building. 8B stories, steel frame construction; decorative brick, painted terra-cotta and stucco facade; galvanized iron cornice and belt course; three-part vertical composition; Renaissance-Baroque ornamentation. Owner: Fair Market Properties LLC. Architect: G. Albert Lansburgh. 1922.

Composed of the Warfield Theater and attached office space, the Warfield Building was purchased for $12 million in 2005 by David Addington, principal at Fair Market Properties LLC, Atlanta. The theater lease was taken over in May 2008 by Goldenvoice Presents, part of the Anschutz Entertainment Group,* after the acrimonious departure of Bill Graham Presents (owned since Graham’s death by Clear Channel). Following some minor renovation work on the theater, concerts were resumed in September 2008.

*Anschutz Entertainment Group is owned by multi-billionaire Philip Anschutz, who also owns the San Francisco Examiner.

Source: San Francisco History Center, S.F. Public Library

Warfield Building, 1922.

Warfield Storefronts

Caryatids, Warfield Theater

Theater Entrance

Source: San Francisco History Center, S.F. Public Library

Loews Warfield, opening day, 1922.

Opened on 23 May 1922 as Loews Warfield, the theater was named for People’s Vaudeville Company co-founder David Warfield (born David Wohlfeld in San Francisco on 28 November 1866), one of Marcus Loew’s best friends and one of the first investors in the corporate empire that became Loews-MGM. Originally a venue for both vaudeville and cinema, the theater operated as a first-run movie house until the late 1970s, when it began to occasionally host live music by artists such as Siouxsie and the Banshees and Devo. The theater was leased by Bill Graham Presents about the same time that Graham closed down his North Beach venue, Wolfgang’s, after a suspicious fire. Since then, just about every top name in rock has performed at the Warfield. Jerry Garcia set the record for most performances at the theater by appearing eighty-eight times with the Grateful Dead and various side bands.

Stairway, Warfield Theatre

Proscenium and Loge, Warfield Theatre

Proscenium Detail, Warfield Theatre

Crest Theater

“Crazy Horse”

Crest Theater Site. 980 Market Street.

Next door to the Warfield, what is now the Crazy Horse “Gentlemen’s Club” was for most of its life a cinema. Opened in 1909 as the Lesser Nickelodeon, it became Grauman’s in 1910, the Maio Biograph in 1912, the Circle in 1924, New Circle in 1932, Newsreel in 1939, Cinema in 1949, Crest in 1958, Egyptian in 1976 and the Electric in 1981. The theater was reincarnated as the Crazy Horse in 1994.

Source: San Francisco History Center, S.F. Public Library

Crest Theater, 1967.

Hale Brothers and Wilson Buildings

“Hale Brothers”

Hale Building. 989 Market Street.

Source: San Francisco History Center, S.F. Public Library

Market and Sixth, 1905.

Source: Bancroft Library, UC Berkeley

Market and Sixth, 1906. Left relatively unscathed by the earthquake, the Wilson and Hale Brothers buildings (on the left) were gutted by the ensuing fire; however, both buildings were soon after restored. In 1912 a new Hale Brothers Building—the fourth, largest, and last of the company’s San Francisco department stores—was built on the corner of Fifth and Market.

Source: Bancroft Library, Jesse B. Cooke Collection

Market and Sixth, 1920. Partly visible on the left is the Hale Brothers Building.

Source: San Francisco History Center, S.F. Public Library (Photo: Gabriel Moulin Studios)

Wilson and Hale Brothers buildings, 1944.

Source: San Francisco History Center, S.F. Public Library (Photo: Alan J. Canterbury)

Hale Brothers Building, 1964.

St. Francis Theater

Soon, all will be new, bright, shiny, and soulless — and the legends will be gone forever, ground to dust by the relentless jackhammers.

–Herb Caen

“Final Curtain”

St. Francis Theater. 965 Market Street.

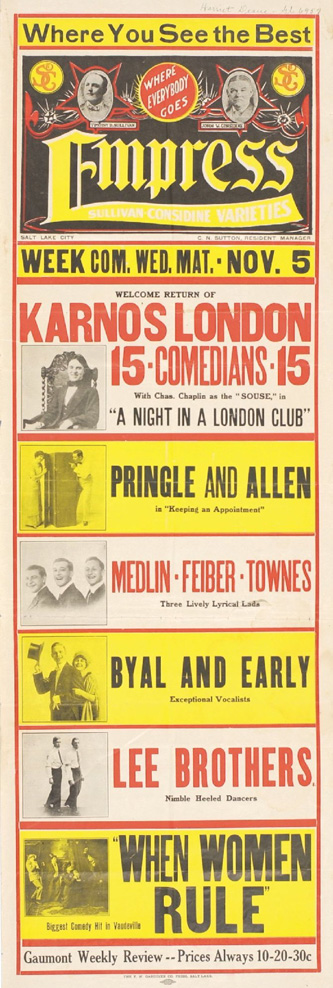

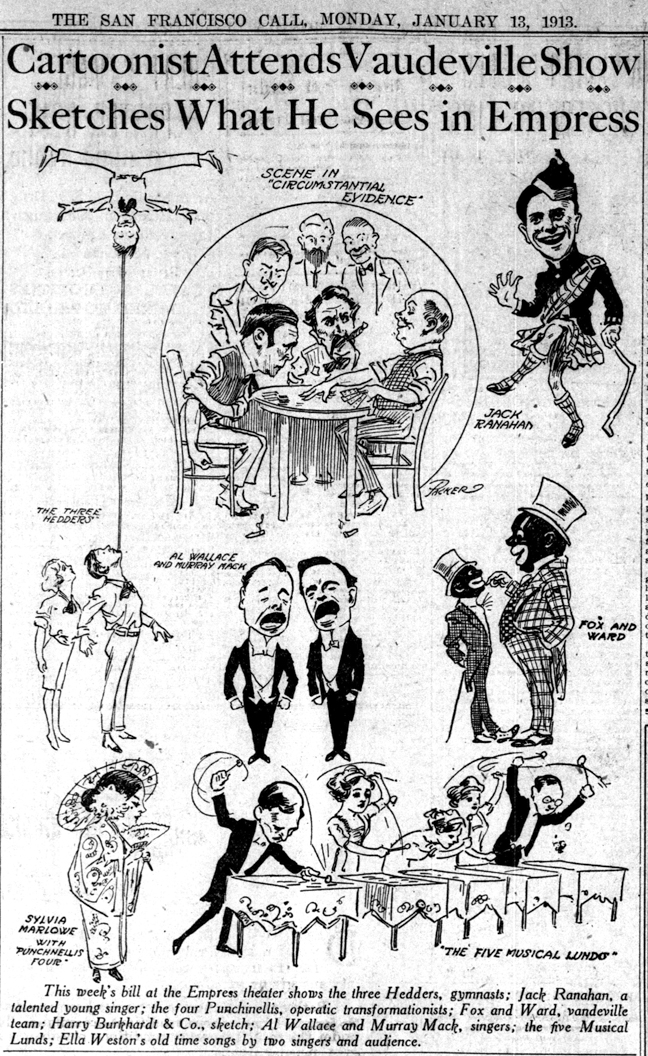

Closed since May 2001, the St. Francis is one of Market Street’s oldest cinemas. Designed by John Galen Howard, architect of the UC Berkeley campus and one of California’s most respected architects, the theater opened in 1910 as the Empress, then was taken over by Sid Grauman and renamed the Strand in 1917, becoming the St. Francis in 1924. When the theater was twinned in 1968, one screen was christened as the Baronet and the other screen retained its name as the St. Francis; in 1976, the theater was renamed for the last time as the St. Francis I and II.

Source: Gensler & Associates

Proposed CityPlace Mall

After ignoring numerous oversights and flaws in the draft Environmental Impact Report that had been painstakingly enumerated in public commentary, in 2010 the San Francisco Planning Commission rubber-stamped the final EIR for CityPlace, a five story shopping mall and parking garage that will replace everything from the St. Francis theater to the Kress building. In an effort to circumvent this decision, attorney and preservationist Arthur Levy, who had several years earlier saved the historic Harding Theater from demolition, arranged a special hearing with the Board of Supervisors and the planning department. Sadly, five hours of presentations by architects, attorneys and preservationists, including me, were to no avail against the hubris and prevarication of a hostile planning department. The supervisors voted unanimously in favor of the developers and the St. Francis will soon be just a memory. (see also “Farewell to the St. Francis”).

Source: San Francisco History Center, S.F. Public Library

Empress Theater, 1910. Note the horse-drawn carriages parked in front of the theater.

Source: Anonymous

Poster, circa 1911.

Source: Anonymous

Charlie Chaplin, circa 1911.

Source: California Digital Newspaper Collection

Clipping, San Francisco Call. 13 January 1913.

Source: San Francisco History Center, S.F. Public Library

Interior, St. Francis Theater, 1925.

Source: San Francisco History Center, S.F. Public Library

St. Francis marquee, 1925.

Source: San Francisco History Center, S.F. Public Library (Photo: Alan J. Canterbury)

St. Francis marquee, 1964.

Source: San Francisco History Center, S.F. Public Library

St. Francis Theater and storefronts, 1953.

“St. Francis”

St. Francis Theater and storefronts.

No sign remains of the retail shops that once thrived in the St. Francis storefronts, all of which were boarded-up in 2002.

Pantages Theater

“Pantages”

Unoccupied building (formerly Pantages Theater, later Kress and Company). 939 Market Street. Seven stories, steel frame construction; facade completely stripped and remodeled. Architect: B. Marcus Priteca. 1911.

The Pantages Theater opened on 30 December 1911 and operated until February 1926, when the new Pantages Theatre (later the Orpheum) opened at 1192 Market Street. Soon thereafter, the building became a retail store for the Kress chain, and from the 1980s until 2007 it was occupied by the Social Security Administration; the building has been unused since then.

Source: San Francisco History Center, S.F. Public Library

Pantages Theater, circa 1920.

Source: San Francisco History Center, S.F. Public Library

Kress and Company, circa 1926.

Source: San Francisco History Center, S.F. Public Library

Kress and Company, 1956.

Market and Mason

Source: Bancroft Library, U.C. Berkeley

Market and Mason, circa 1890. The tall, domed building near the center is the Baldwin Hotel at Market and Powell.

Source: California State Library

Market near Mason, circa 1920. Note the Pantages Theater on the right.

“Near Market and Mason”

In between the check-cashing companies, liquor stores, and boarded-up buildings, numerous short-lived enterprises sell cheap imported clothing and electronics of questionable origin.

Source: California State Library

Market and Mason, circa 1920. Center right is the largest and last of Hale Brothers Department Stores on the corner of Fifth and Market.

“Market and Mason”

Along this row of storefronts, the frequent changeover in proprietorship is evident in the painted-over business names on tattered canvas marquees.

Garfield Building and Pix Theater

“Pix”

Pix Theater Site (Garfield Building). 942 Market Street Seven stories, steel frame construction; brick facade, terra-cotta spandrels and lintels, galvanized iron cornice, double-hung sash. Architect: Reid Brothers. 1907.

Opened on 4 April 1946, the Pix was so small that it didn’t even issue tickets. Instead, there was a turnstile that was activated by the cashier after admission was paid. The theater had no lobby—restrooms, lounge and snack bar were downstairs. The Pix, like the Centre, was a “shooting gallery” theater, with rows of six seats on either side of a center aisle. Unlike the Centre, however, the Pix was just wide enough for a small, 1.85:1 screen to be workable. Amazingly, the tiny theater was air-conditioned, and in fact for years was the only theater in San Francisco that could boast of this. Programmed as a grind house (a theater with continuous showings of violent or sensational films), the Pix showed three “action hits” and six color cartoons for an admission price of fifty cents. On 25 August 1950, the Pix became the Newsvue, which showed only newsreels on weekdays and a program of twenty-five cartoons on weekends. Audiences grew tired of newsreels, however, and in 1955 the newly renamed Pix resumed its former grind house programming. Toward the end of its life, the Pix became an adult theater and, after closing for the last time in 1972, was converted to retail space.

Source: San Francisco History Center, S.F. Public Library

Market and Mason, 1955. The Pix marquee is visible near the center of the photo, below the dentist office blade sign.

Esquire and Telenews Theaters

Source: San Francisco History Center, S.F. Public Library

Esquire and Telenews Theaters, 1943. Newscopy: “Smoke from film and equipment blazing from a projection booth fire darkens the front of the Telenews Theater in Market Street, where trolley cars and automobiles were tied up in long lines and thousands watched the (?) One man was hurt, 30 safely filed out of the theater.”

Source: San Francisco History Center, S.F. Public Library

Esquire and Telenews Theaters, 1964.

“All Gone”

Esquire and Telenews Theater Sites. 934 and 930 Market Street.

Source: San Francisco History Center, S.F. Public Library

Market Street Theater, 1910.

The Esquire, opened in 1909 as the Market Street Theater, was one of the first large-scale cinemas to open on Market Street. After a series of name changes over the years, in 1940 the theater was finally named the Esquire. During the ‘40s, the theater showed first-run Abbott and Costello comedies and Universal horror films, leavened intermittently with Technicolor extravaganzas. By the 1960s, the theater was showing mostly Roger Corman films and other American International fare. The Telenews Theater opened on 1 September 1939, featuring newsreels of the Nazi invasion of Poland. Both the Esquire and the Telenews were demolished in 1972 to make way for the new Hallidie Plaza.

Source: San Francisco History Center, S.F. Public Library

Market Street and new Fifth Street extension, 1973. Nearly all the buildings between Powell and Mason were demolished during BART construction. The North-of-Market extension of Fifth Street connected with Anna Lane, later renamed Cyril Magnin Way.

Market and Powell

Source: Bancroft Library, Jesse B. Cooke Collection

Market near Powell, circa 1898. On the left is the Baldwin Hotel on the northeast corner of Powell and Market; the Parrott Building, otherwise known as the Emporium Department Store, is the large building in the center.

Source: California State Library

Powell and Market, circa 1916. On the left is the Techau Tavern, replaced in 1920 by the Bank of Italy Building; across Powell Street is the Flood Building.

“Powell and Market”

Bank of Italy Building. 1 Powell Street. Architect: Walter Danforth Bliss. 1920.

Flood Building. 870 Market Street. Architect: Albert Pissis. 1904.

In 2005, the historic Bank of Italy building was purchased by SPI Holdings for an undisclosed price from Wilson Meany Sullivan, who had spent $35 million in renovations that included a seismic retrofit, a new floor, and conversion of the 90,000-square-foot building to 25,000 square feet of retail and forty-nine rental apartments. The retail tenant is Forever 21, a purveyor of trendy fashions for women. The Bank of America has moved its branch to the basement level. As of early 2008, monthly rent for a one-bedroom apartment is $3,900.

“Storm Season”

Flood Building. 870 Market Street. Twelve stories. Steel frame construction, Colusa sandstone facade (extensively restored mid-1990s). Architect: Albert Pissis. 1904 (restored following 1906 earthquake and fire).

Albert S. Samuels Clock. 856 Market Street.

James C. Flood (1826-1889), one of the Silver Kings of the 1870s, was the financial mind behind the Consolidated Virginia mine, which yielded the largest mineral strike in U.S. history. The grandiosity of the building that bears his name reflects his tremendous wealth. Truly a monumental edifice, its facing is entirely of hand carved stone and the elaborate ornamentation looks like an architect’s holiday. The four-faced clock, now an historical landmark insured by Lloyd’s of London, was built by jeweler Albert S. Samuels in 1915.

Source: Bancroft Library, UC Berkeley

Baldwin Hotel, 1898. Before the Flood Building there was Elias J. Baldwin’s hotel and theater, here photographed after the fire that destroyed it (for more about “Lucky” Baldwin and his hotel, see Part III: The Tenderloin).

Source: San Francisco History Center, S.F. Public Library

Flood Building, 1905. On the left is the St. Anne’s Building, destroyed in the 1906 fire.

Source: San Francisco History Center, S.F. Public Library (Photo: Alan J. Canterbury)

Woolworth’s, Flood Building, 1964. One of my favorite features of the old Woolworth’s store was a fifty-cent photo booth, which I would often visit on my way to classes at the San Francisco Art Institute on Chestnut Street in the late ’60s and early ’70s. In those days, the fare for all Municipal Railway lines, including cable cars, was twenty cents.

“Abyss”

Vantage Point: Marines Memorial Hotel. 609 Sutter Street.

When a building has been around for a while it shows signs of time’s passage, revealing its history in a wonderfully arcane visual language. What I captured with my camera here can’t be seen from street level; it is a hidden world. With the encroachment of new skyscrapers in the distance, this image symbolizes for me what is happening to all cities in America today. In the forty-three years I have lived in San Francisco, I’ve witnessed the passing of much that was admirable and unique. It saddens me that Part II is largely an epitaph for what used to be.

Except where otherwise indicated, text and photos on this site are copyright © 2004-2015, Mark Ellinger. Any use and/or duplication of this material without prior written permission from the author is prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Mark Ellinger and with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.