By ANNE BARNARD

DECEMBER 27, 2015

ISTANBUL — When Alan Kurdi’s tiny body washed up on a beach in Turkey, forcing the world to grasp the pain of Syria’s refugees, the 2-year-old boy was just one member of a family on the run, scattered by nearly five years of upheaval.

As a Turkish officer lifted the boy from the shallow waves at the edge of the Mediterranean Sea, one of Alan’s teenage cousins was alone on a bus in Hungary, fleeing the fighting back home in Damascus.

An aunt was stuck in Istanbul, nursing a baby, as her son and daughter worked 18-hour shifts in a sweatshop so the family could eat. Dozens of other relatives — aunts, uncles and cousins — had fled the war in Syria or were making plans to flee.

And just weeks after Alan’s image shocked the worldin September, another aunt prepared to do what she had promised herself to avoid: set sail with four of her children on the same perilous journey.

“We die together, or we live together and make a future,” her 15-year-old daughter said, concluding, as have hundreds of thousands of other Syrians, that there was no going back, and that the way to security led through great risk.

This image of Alan’s body washed up on a beach in Turkey led to an outpouring of concern for Syrian refugees. Since then, at least 100 more children have drowned in the Mediterranean Sea.

NILUFER DEMIR, VIA AGENCE FRANCE-PRESSE — GETTY IMAGES

Alan, whose mother and brother drowned with him, belonged to a sprawling clan from Syria’s long-oppressed Kurdish minority. But for most of his closest relatives, that identity was secondary to the cosmopolitan ethos of the Syrian capital, Damascus, where they grew up. They barely spoke Kurdish, identified mainly as Syrian and joined no faction.

So when war broke out, and political ties, sect and ethnicity became life-or-death matters, they were on their own.

Interviews with 20 relatives, in Iraqi Kurdistan, in Istanbul, in five German towns and by phone in Syria, tell a story of a family chewed up by one party to the Syrian conflict after another: the Syrian government, the Islamic State, neighboring countries, the West.

Since Alan’s death, at least 100 more children have drowned in the Mediterranean. A million refugees and migrants entered Europe this year, half of them Syrians, part of the biblical dispersion of a country where half the population has fled.

Alan’s father, Abdullah, who is 39, sometimes blames himself, wishing he could turn back time and not get on the boat. He was trying to steer it in the chaos when it foundered in the waves.

But even for Abdullah’s sister Hivrun, grieving her nephew, the calculus remained in favor of risking her children to save them. Weeks after Alan died, she tried again to start for Germany. Once again, she and her children clambered onto a rubber raft.

Kurdish Roots

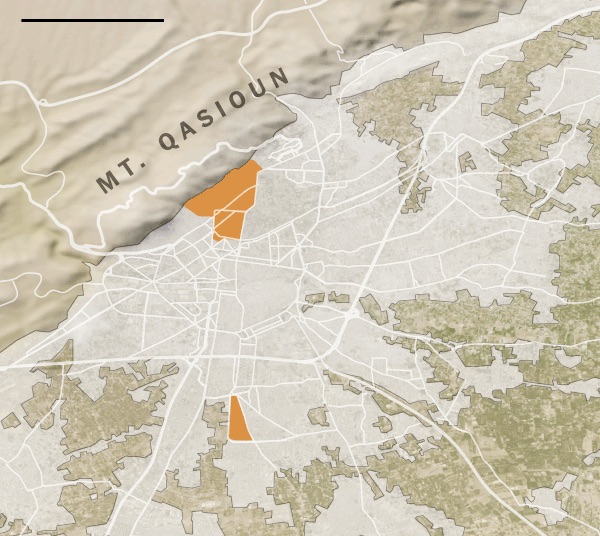

Alan’s grandfather was born in Kobani, a mostly Kurdish enclave near the Turkish border in the north. After compulsory army service, he moved to Damascus looking for work and settled in the mostly Kurdish neighborhood of Rukineddine, on the slopes of Mount Qasioun. He opened a barbershop and married a Kurdish woman who considered herself above all Damascene.

Rukineddine grew fast, with jumbled, unplanned housing and steep, narrow alleys cramming in poor rural workers, the kind of place where rebellion would later flare.

They had six children. They remember living modest lives not much affected by tensions between the government and Kurds. They spent the summers harvesting olives in Kobani, but saw themselves as city kids. Most left school after ninth grade to learn the family’s barbering trade.

Fatima, the oldest daughter, was the first to emigrate. In 1992, she moved to Canada to marry an Iraqi Kurd. They soon divorced, and she raised their son. Working nights in a printing plant, she caught the attention of a kindly boss.

“She said, ‘Every night I’ll teach you 10 English words,’” Fatima, known as Tima, recalled recently. “The rest I got from watching ‘Barney’ with my son.”

English led to a hairstyling license, jobs at high-end salons and citizenship — successes that made the family’s later journeys possible.

3 Miles

Rukineddine

EAST GHOUTA

Damascus

Yarmouk Camp

SYRIA

By The New York Times

A commanding presence, Fatima became her siblings’ source of advice, information and emergency cash. When war broke out, she became their fiercest advocate, supplying the plans and means to seek asylum in the West and, later, the political savvy to make Alan’s death a force for change.

But before the war, the rest of the Kurdis were not thinking of leaving Syria. They were putting down roots in the patchwork of communities that gave Syria its richness. They acquired in-laws and property in the Damascus suburbs, in Kobani and in the bustling Palestinian district of the Yarmouk refugee camp — all places soon to be shattered by violence.

Driven From Damascus

The ripples of conflict reached the capital in the spring of 2011, just as Abdullah Kurdi was starting a family with his wife, Rihanna, a cousin from Kobani.

As the protests, inspired by other Arab uprisings, began to spread against the government of President Bashar al-Assad, Rihanna headed back to Kobani to give birth to Ghalib, Alan’s older brother. Abdullah went back and forth, working in the family’s Damascus barbershop.

Alan Kurdi’s body was recovered near Bodrum

By The New York Times

Some of the Kurdis sympathized with the initially peaceful demonstrations, but most avoided involvement. They feared going into details, since some relatives are still in Damascus. Abdullah said only, “I participated.”

The government cracked down across Syria, and the neighborhood quickly came under pressure. Security forces, always able to detain people at will, became jumpier, quicker to scapegoat Kurds or anyone without political connections.

“After the revolution started, I saw the differences between me and others, the racism,” Abdullah recalled. “Any simple policeman can accuse you. If someone writes a fake report against me, saying this Kurd did this or that, I will never come back.”

One day, officers burst into the family home of some of the Kurdis’ in-laws and dragged away two brothers, who had no known political involvement. They have not been heard from since.

Next, Alan’s cousin Shergo, 13, saw a friend die, shot through the neck by the police while protesting outside school.

Government artillery began shelling the restive suburbs of Damascus — where an armed insurgency was taking shape — from bases atop Mount Qasioun, up the slope from Rukineddine. The army guns were so close that the pressure of outgoing blasts cracked the wall of a family house.

The Kurdis were on the receiving end of the shelling, too, in the suburb of East Ghouta, where one of Alan’s aunts lived with her family. Clashes also erupted in the Yarmouk camp, where another aunt lived with her Palestinian husband. He was wounded in shelling.

Those two aunts brought their families home to Rukineddine. But it hardly felt safer.

The flight to Kobani came after Shergo and another teenage cousin witnessed a suicide bombing in the street. Flesh stuck to a wall, and shrapnel lodged in one boy’s leg.

At the hospital, security officials questioned the boys, who were afraid to say what they had seen. The secret police started asking to talk to the Kurdi men.

“So I said: ‘Let’s go. Let’s leave,’” Shergo’s mother, Ghousoun recalled. “It’s better than if they take us.”

Kobani seemed like a refuge then, as Kurds there tried to establish a safe semiautonomous zone. But, Abdullah lamented, “It didn’t work out that way.”

Life on the Run

At first, the problems were strictly economic. Kobani offered few jobs. Abdullah went to Istanbul to work, while his wife raised Ghalib, and later gave birth to Alan, sometimes spelled the Turkish way, Aylan. (Previous reports put his age at 3.) Ghousoun and her family lived for a time in a sheep stable; she made money by bringing clothes from Damascus to sell.

“I suffered a lot, because I’m a very neat person,” Ghousoun recalled later, in her small and spotless Istanbul apartment.

Ghousoun, married to Alan’s uncle Mohammad, with their children in their apartment on the outskirts of Istanbul this month. Mohammad’s sister Fatima, who is in Canada, raised $20,000 to sponsor his family for asylum there. But Canada required proof of refugee status, which Turkey does not grant.

MAURICIO LIMA FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES

Then a new threat arose. The extremist Islamic State group split from others fighting Mr. Assad, declared a state, and preyed on Kurds and other minorities.

Ghousoun’s travels grew perilous. Her accentless Arabic and conservative dress hid her Kurdishness at Islamic State checkpoints, but made her suspect at Kurdish roadblocks.

By September 2014, the Islamic State was shelling Kobani. Word came that the militants would invade. Families fled toward Turkey, and some were caught between Islamic State fighters and the border fence.

There, fighters grabbed Ghousoun’s husband, Mohammad, Abdullah’s brother. They spoke Arabic, but their accent was not Syrian.

“They beat and beat and beat him with a gun, my husband,” Ghousoun said later, sobbing. “In front of me.” Next, she said, they handed her son Shergo, by then 15, a gun.

“Shoot your father,” they told him.

“They kept saying we were infidels,” Ghousoun said. “But we are not.”

She collapsed on the ground, calling on God, begging the fighters, and somehow, she said, “they took mercy.”

The family spent days looking for a crossing, with hundreds of other Kurds. Finally, the group tried to breach the border. The Turkish police beat most of them back, but a Kurdish woman on the Turkish side hid Ghousoun’s family in her cowshed.

Back in Kobani, the Kurdi clan’s olive groves were burned, houses destroyed, and 18 relatives slaughtered.

Many of the survivors made it to Istanbul, and a new round of ordeals.

A Way Station in Turkey

Abdullah had managed to send money from Istanbul by working, and sleeping, in a clothing workshop. But when his wife and children finally joined him, he said, the burden overwhelmed him, “like a chain on my hands.”

The only apartments he could afford were so far from his work that he had to quit his job, instead lifting 200-pound bags of cement, making $9 per 12-hour day.

Ghalib and Alan jumped into his bed each morning to snuggle before he slathered them with ointment for their eczema, a ritual that he relished, even as he fretted over the cost of the balm.

By The New York Times

“They sat in the house all day,” he said, choking with tears. “The only thing they were waiting for was me.”

Other Kurdis fared no better in Turkey. Syrians there were often invited to bring their children to factory job interviews, but found, instead of day care, children packing goods in boxes. Jobs disappeared when new Syrians arrived, willing to work for less, and employers sometimes withheld pay. Abdullah’s sister Hivrun cleaned hotel rooms, dozens a day. Ghousoun washed dishes in a restaurant; her son Shergo worked in a clothing sweatshop.

The promise of emigrating to the West seemed distant. In Canada, Alan’s aunt Fatima raised $20,000 to sponsor Mohammad for asylum, with his wife, Ghousoun, and their five children. But Canada required proof of refugee status. Turkey granted Syrians only guest status, which Canada did not accept.

Hivrun applied for resettlement in Germany. Last summer, she received a date for her first interview: Sept. 27, 2016.

Options dwindling, Abdullah, Mohammad and Shergo traveled west and crossed a river to Greece. The police beat them with sticks, then sent them back in a rubber raft.

In June, Mohammad took a smugglers’ boat to Greece and made it to Germany.

Alan’s cousin Yasser, 16, fled Damascus to avoid the draft. He, too, boarded a smuggler’s boat out of Turkey.

Disasters at Sea

Hivrun and her husband were the first to take children to sea. They took four children and an adult nephew south to Izmir, the epicenter of the smuggling trade in Turkey.

Smugglers packed them in windowless vans, left them alone in a wooded area to dodge the police, then put them on a raft aimed at a Greek island a few miles off, but the raft had a broken engine. Only when Hivrun objected was the trip aborted.

On the next try, they were out to sea when water started rushing in. Hivrun saw a Turkish coast guard boat and shouted for help, not stopping even when other passengers, who preferred to risk it, angrily shushed her.

Hivrun’s husband and the older children wanted to try again. Hivrun refused. She took the children back to Istanbul, and her husband and nephew sailed off to Greece.

Soon afterward, Abdullah tried the voyage with his family. “We had decided to go to paradise,” Abdullah explained, a better life, whether in Europe — or the hereafter.

Hours after Alan’s drowning, Abdullah told the story in anguish: The small boat foundered and flipped a few minutes into the journey. He tried to hold on to Ghalib and Alan, calling to his wife, “Just keep his head above water!” But all three drowned, one by one.

Other survivors added new details: Alan cried as water sprayed his eyes; an older woman took him on her lap; the smuggler leapt out, and Abdullah took the tiller. Nervous and inexperienced, he swerved over the waves, telling his children, “I’m with you; don’t worry,” just before the boat capsized. One woman remembered Abdullah, in the water, kissing one of his boys.

In the news media blitz that followed, some reports, quoting an Iraqi couple who lost two children in the disaster, said Abdullah was a smuggler. But it is a standard smugglers’ practice to have an ordinary refugee steer, often in exchange for a discount, and in a later interview, the Iraqis said they believed Abdullah was merely the designated refugee pilot.

Abdullah says that he got no discount, and that he and others tried to take control of the boat because “someone had to.”

Regardless, one thing is clear: Abdullah lost his family.

Little Solace

Within hours, Alan’s aunt in Canada, Fatima, leapt into action.

From her home near Vancouver, she took calls from the news media, blaming Canada’s red tape and the world’s indifference. Soon she was touring Europe to advocate on behalf of refugees.

“Those kids were born when the war was on,” she recalled telling António Guterres, the United Nations’ high commissioner for refugees. “And they die with the war still on.”

Abdullah Kurdi in the piano bar of a hotel in Erbil, in Iraq’s Kurdistan region, less than a month after losing his wife and two sons. “I have become a shadow,” he said.

BRYAN DENTON FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES

Her raw message helped spur Western countries — briefly, at least — to open their doors to Syrians.

But none of that changed the calculus for the Kurdis.

In the remote German town of Villingen, on the edge of the Black Forest, Ghousoun’s husband, Mohammad, worried for his family in Istanbul. He emerged one night from a barracks-like refugee shelter ringed with concertina wire and confided his dilemma: It could take a year or more to bring his family legally, so his decision to keep them off the dangerous boats meant indefinite separation.

“The most important thing,” he said, “is to be together.”

For the same reason, Hivrun broke her vow never to set sail again, determined to rendezvous with her husband. This time, she and her children made it.

In Meppen, Germany, a few weeks later, her children recounted the wet, terrifying moments on the boat — “a horror film!” one said — but now they were eating ice cream with a view of yellow autumn leaves.

Their father was stuck in a separate camp, three hours away. But after several weeks of haranguing the authorities, they got their wish: They could move, all together, to an apartment.

To the south, near Heidelberg, Yasser, the teenager who fled alone, was even more bullish on Germany, pinning the colors of its flag over a bed with a heart-shaped plush pillow. As an unaccompanied minor, he receives benefits like carpentry classes and excursions.

He misses his mother, but he already speaks passable German, knows the city and even has a German girlfriend. Wearing his hair in an Elvis-like pompadour, he plans to open a barbershop and study acting.

“I don’t want to lie to you and tell you that I am not happy,” he said. “I am!”

Ghousoun and Mohammad expect to be reunited in Canada on Monday, among 10,000 Syrians admitted by a new Liberal government. Fatima has a job for Mohammad in her new salon, where the sign over the door reads “Kurdi.”

“People always need a haircut,” she said.

A Father’s Heartache

A few weeks after the tragedy, Abdullah sat, angular and stiff and out of place, on a leather sofa in the piano bar of a gilt-trimmed hotel in Erbil, in Iraq’s Kurdistan region. The sea had sheared him of all trappings of identity: his documents, his sisters’ phone numbers, even his dentures.

“I have become a shadow,” Abdullah said.

Mohammad, Ghousoun’s husband, outside a refugee center in the German town of Villingen, on the edge of the Black Forest, where he lives alone.

MAURICIO LIMA FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES

After he buried his family in Kobani, in three graves on a treeless plain, he was whisked to Erbil by the powerful Barzani clan. He had resolved to use the spotlight on his grief to aid other Syrians, and the Barzanis were promising help.

Barely understanding Kurdish, he went gamely to meetings with the rich and powerful, and delivered aid to refugee camps, happiest when playing with children.

But he often seemed dazed. He wore a single plain, khaki-colored outfit every day, refusing to let his benefactors buy more. He had never been in a place like this, with a $99 Sunday brunch, and could not stop thinking: “Where was all this when my children were alive?”

He called his Canadian sister, Fatima, who was collecting his family’s things in Istanbul. She was coming to see him, and the thought of it brightened him. He asked her for his sons’ favorite stuffed dog, the one with the tongue sticking out, or maybe the Teletubby doll with the missing eye that he had promised to fix.

“I want something,” he said, “with their smell.”

Reporting was contributed by Hwaida Saad from Turkey and Beirut, Lebanon; Karam Shoumali from Istanbul; Amro Refai from Germany; Tim Arango from Baghdad; Ben Hubbard from Kobani, Syria; and Kamil Kakol from Erbil, Iraq.

© 2015 The New York Times Company