The historian has completed his epic on the rise of the US right – just in time for Donald Trump’s attempt to hold on to his throne

Less than three months before the most consequential American election of modern times, Rick Perlstein has completed his epic history of the forces that ultimately put Donald Trump in power. Reaganland, Perlstein’s fourth volume on the rise of US conservatism from 1960 to 1980, is out on 18 August.

Including notes, the book runs to more than a thousand pages. An hour or so before we speak, however, Perlstein puts out a rather shorter statement: a tweet.

“Open letter to press. I’ve given my last interview about the ’68 election’s lessons for 2020. Given Trump’s tweet on postponing, the political media’s determination to bound its discussion within the frame of normal politics is downright dangerous, and I won’t be complicit.”

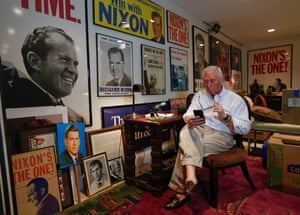

So I don’t ask Perlstein to compare Richard Nixon – the subject of volume two, Nixonland (2008) – with a president repeating his “law and order” message and who the same day says “universal mail-in voting” will lead to “the most INACCURATE & FRAUDULENT election in history”, and therefore suggests the US might “Delay the Election until people can properly, securely and safely vote???”

Trump can’t delay the election. But he can fight and lie and cheat, as Nixon did, and that seems likely to keep reporters knocking on Perlstein’s door. His tweet, he says, came “from a frustrating interview in which I said over and over again: ‘The real thing you need to be talking about as a reporter … is parallels to what was going on in South America in the 1970s and Europe in the 1930s.’”

His point is that when Trump “keeps doing things proven unpopular to all but the fascistically inclined, maybe he sees his audience as the fascistically inclined – those more useful to him for keeping permanent power than mere voters”.

On the phone, from Chicago, he expands.

“By talking about how many electoral votes [Trump’s] trying to get in the suburbs with his law-and-order appeal, you’re kind of doing active harm to contemporary understanding. That sort of consensus frame, that things aren’t really as bad as they seem, is a story that gatekeeping media elites tell about the world, that makes them actors in the story, not merely commentators.”

A man of the left, Perlstein agrees his books are as much about the failures of liberalism and the media as the success of the right.

“The only reason we’re talking about 1968 is because Trump wants to talk about 1968. He sets the agenda by tweeting ‘law and order’ and ‘silent majority’. That’s his story.

“My shorthand is history is process, not parallels. There really can’t be a historical parallel. You can’t step in the same river twice or even once because the thing that happened in 1968 happened and we were responding to what happened. Even if there are similarities.

“It’s kind of a paradox. It’s really important to understand history in order to be a better citizen in the present but sometimes history can take you further away from understanding, instead of closer.”

‘The whole whale’

Over thousands of pages, from Goldwater v Johnson (Before the Storm, 2001) to Reagan v Carter, Perlstein seems to seek to embrace all understanding. He’s been called the “hypercaffeinated Herodotus of the American century” and you suspect the first part at least must be right, if only so he can keep up the pace. TV broadcasts and newspaper columns used as primary sources create a very American cacophony which Perlstein does not so much tune out, in order to show what is really going on, as turn all the way up to 11.

Like trying to keep up with American politics in any election year, reading Perlstein can be like trying to drink from a firehose. There’s something Melvillean about the sheer scale of the work, four leviathans to make up a whole.

“The whole whale,” he laughs, wary. “If I had a gun to my head [and someone asked] ‘How is your book like Moby-Dick?’ I would definitely say that like Melville, I’m trying to get at the deepest wellsprings of psychological and political issues about how human beings body together as a community and get things done.”

“It speaks to what is most profound to me, which is basically contributing to a civic conversation about this nation and its prospects. I write it as an American for Americans.”

He also writes in the shadow of the author of American Pastoral, who died in 2018.

“For the original working subtitle for Nixonland,” Perlstein says, “I borrowed a phrase from one of Philip Roth’s novels: the politics and culture of the American berserk. I mean, if you’re not writing about the berserk, you’re not writing about America.”

‘Writing is mind control’

In Reaganland, one after another, major players take the stage. More than 40 years later, many are still there.

Joe Biden was elected to the Senate in 1972. In Reaganland, in 1980, he is in his late 30s, “the latest in a long line of Democratic up-and-comers tagged with the coveted sobriquet ‘Kennedyesque’”, seen supporting the beleaguered Jimmy Carter but “dropping remarks about running for – and some day becoming” president himself.

Trump is there too, buzzing around Reagan’s campaign launch in New York City in the summer of 79, already subject to grave doubts about his character, nonetheless “held up as just the tonic a depressed city needed to get its swagger back”.

In a book in which picaresque narrative and forensic political analysis sit side by side, Perlstein constructs a typically vivid set piece.

“It seems absolutely absurd that [Reagan] would choose to do this in New York because New York was basically such a shithole at the time. I have this whole riff about how the buses can only travel 30 miles an hour on the freeway because the tires are so crappy. There’s an epidemic of bank robberies going on and the bank robbers are not these kind of professionals that the cops are used to dealing with – they’re kind of just poor, desperate young men.

“It all comes from a single hour-long New York City newscast that somebody put up on YouTube. And when you go to my website, you can click on that because wherever possible, all the source notes lead to where you can find them.”

Perlstein uses more traditional sources too, Reagan’s letters and Carter’s diaries among them, and cites deep debts to contemporary political reporting. It all creates a remarkably intimate feel.

“I always say that writing is mind control,” he says. “You’re basically telling a person what sort of mood to feel, what sort of thing to think, how to experience the passage of time while they’re kind of consuming the text. What I’m trying to do is to place a person in this civic dilemma of a person living through these events.”

Back to 2020, a whole year of civic dilemma. Roger Stone, who survived Nixon’s fall and was recently spared prison by Trump, also appears in Reaganland, a man on the move himself.

“After Nixonland came out,” Perlstein says, Stone “came out with one of his books about Nixon [and] basically proposed that we go on tour together: ‘We can sell a lot of books and make a lot of money.’ At the time he was very adamant he was no longer a Republican. He was running for the Senate, I believe, from Florida as a Libertarian. The depths of his attention-starved behavior. .

“But one of the reasons I kind of renewed the acquaintance online was because I was doing some factchecking about these insane dirty tricks he was doing in the 1977 Young Republicans election where he won that presidency, with Paul Manafort as his campaign manager … that was a news story that Roger Stone won because he was involved in Watergate dirty tricks and this was going to destroy the Republican party if these people ever got anywhere close to the seat of power.

“And … yeah, that happened.”

On Perlstein’s pages, astride public life, Stone’s capers can seem so extraordinary, so shameless, so berserk that they almost come to seem funny.

“We laugh to keep from crying,” Perlstein counters, “and the serious point being made is that as Richard Nixon said, ‘If you want a serious political job done, you hire a rightwing exuberant.’

“These were the people who were, for example, running Ronald Reagan’s primary campaign in North Carolina in 1980. That was Lee Atwater [who] used all the Roger Stone-style dirty tricks … That part of the story is to point out that there’s nothing going on right now in Republican politics that wasn’t kind of latent then.”

Perlstein’s own “engagement with Trump”, he says, “came at a time, in 2015, when I was incredibly burned out from writing about Republican conservatism because it seemed so darn predictable. Then something happened: history is a cunning thing to completely transform the story. I think we always have to be alive and open to that.”

‘Do you take the good with the bad?

How does Perlstein feel about the Never Trumpers, Republicans working to eject a Republican from the White House itself?

“You know, I would have six or seven or eight different strands to think about, kind of untangling that.

“The one that’s the simplest is it’s a patriotic and humane act to say that the person who has in their possession the sole authority to launch a nuclear strike is not a responsible person. That’s the simplest thing and good for them.

“There’s also a cynical interpretation, which I’ve certainly entertained. I wrote a piece reviewing one of the more meretricious Never Trumpers, a guy named Charlie Sykes, who really does seem like a guy who has decided that this is a way that he could kind of escape the local media pool in Wisconsin and become a national figure. In fact he … has this atrocious history in my home town, Milwaukee, of stirring racial tension in order to help Republican candidates.

“These are the guys who cynically think that they’re going to kind of inherit the wreckage and by washing themselves in the blood of the lamb they’re going to be the people who are going to be able to use that claim of innocence in order to be the leaders of the newly reconstituted Republican party.

“Now, things get really interesting when these guys think critically about the Republican culture in which they were marinated. A lot of these guys have done bad in impressive and interesting ways. Max Boot [a Washington Post columnist], writing about how he came into this as a Russian immigrant who was very sincere about fighting communism and hadn’t recognised the extent to which racist dog whistles were such a huge part of the Republican appeal.

“… I mean, do you take the good with the bad? Do you throw out the baby with the bathwater? Ronald Reagan always said a half-loaf is better than no loaf.

“Another complex thread is the next Democratic president – and this is something I was thinking about long before it was Joe Biden, who has a history of seeking ententes cordiale with the Republican party – are they going to feel like this is a constituency that they’re going to have to service as part of their coalition? Which is dangerous.”

It’s a very Perlsteinian response, wide-ranging, multifaceted, but it is given in a very different America from the one in which he started work in 1997, nearly a quarter of a century ago.

Back then, Bill Clinton, the first Democrat in the White House after Reagan, had not yet been impeached. Since then, the right has given us Newt Gingrich and Ken Starr, the Iraq war, Hurricane Katrina, the Tea Party and Donald Trump. How on earth did it come to this?

“It’s almost like I know too much to come up with a simple answer,” Perlstein says. “I don’t have a simple answer. The simplest answer is that we’re in an extraordinary moment.”

Democracy is in peril …

… ahead of this year’s US election. Donald Trump is busy running the largest misinformation campaign in history as he questions the legitimacy of voting by mail, a method that will be crucial to Americans casting their vote in a pandemic. Meanwhile, the president has also appointed a new head of the US Postal Service who has stripped it of resources, undermining its ability to fulfill a crucial role in processing votes.

This is one of a number of attempts to suppress the votes of Americans – something that has been a stain on US democracy for decades. The Voting Rights Act was passed 55 years ago to undo a web of restrictions designed to block Black Americans from the ballot box. Now, seven years after that law was gutted by the supreme court, the president is actively threatening a free and fair election.

Through our Fight to vote project, the Guardian has pledged to put voter suppression at the center of our 2020 coverage. This election will impact every facet of American life. But it will not be a genuine exercise in democracy if American voters are stopped from participating in it.

At a time like this, an independent news organisation that fights for truth and holds power to account is not just optional. It is essential. Like many other news organisations, the Guardian has been significantly impacted by the pandemic. We rely to an ever greater extent on our readers, both for the moral force to continue doing journalism at a time like this and for the financial strength to facilitate that reporting.

You’ve read more than in the last nine months. We believe every one of us deserves equal access to fact-based news and analysis. We’ve decided to keep Guardian journalism free for all readers, regardless of where they live or what they can afford to pay. This is made possible thanks to the support we receive from readers across America in all 50 states.

As our business model comes under even greater pressure, we’d love your help so that we can carry on our essential work. If you can, support the Guardian from as little as $1 – and it only takes a minute. Thank you.